What makes a building a skyscraper? The answer is more complicated than you might imagine.

TALL, high-rise, skyscraper, supertall, megatall crazy tall – you’d be forgiven for feeling confused.

We often use these terms interchangeably when describing structures that are notable for their height, but there is in fact a difference between buildings which just happen to be tall and true “skyscrapers”.

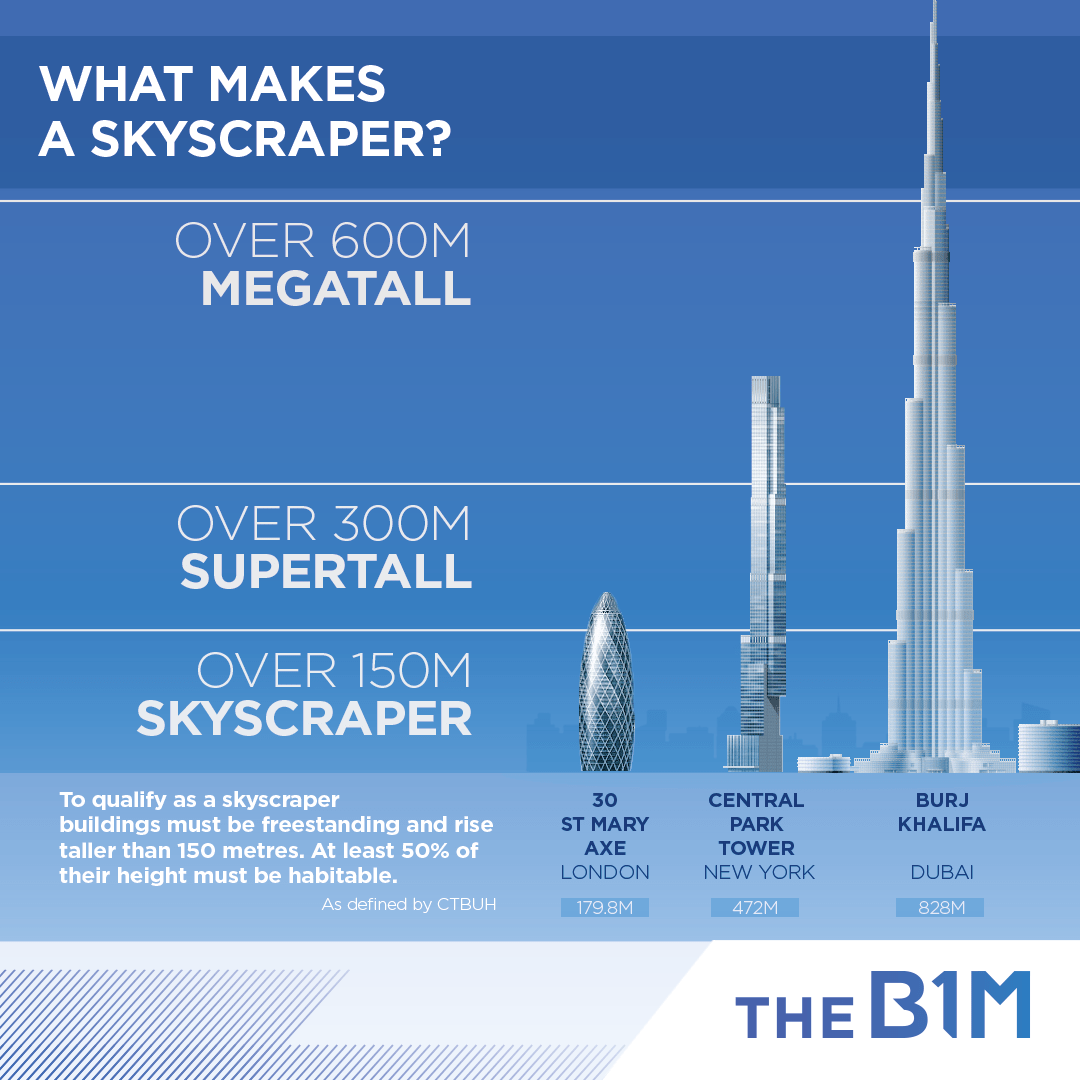

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) in fact defines four categories – Tall Buildings, Skyscrapers, Supertall Skyscrapers and Megatall Skyscrapers.

Here’s the difference between them.

TALL BUILDINGS

So, here’s the thing: there is actually no clear definition on what constitutes a “tall building” and it is to some extent subjective.

A 10-storey structure that is the tallest building in a regional town or low-rise city for example, would easily become lost if it were dropped into the middle of Hong Kong or Chicago.

Some class 50 metres (165 feet) as the threshold for a tall building, but that’s by no means a widely accepted rule.

In reality the term “tall building” is commonly used in our everyday language to describe any structure that rises to a significant or noticeable height.

SKYSCRAPERS

To qualify as a true “skyscraper” a structure must be self-supporting and not require tension cables or supports in order to remain upright.

And there’s another thing - habitable floor space must occupy at least 50% of the structure’s total height. As a result, communication and observation towers like Tokyo’s Skytree or Berlin’s Fernsehturm, while very tall, are not considered to be skyscrapers.

Finally, true skyscrapers must rise to a minimum height of 150 metres (492 feet).

Above: The CTBUH rules on what makes a skyscraper and the key categories compared.

While this used to be a somewhat exclusive club, countless buildings around the world now fall into the skyscraper definition - and as engineering and construction techniques have continued to develop, humankind has pushed the limits of building at height.

As the landscape has changed, CTBUH created two additional categories to distinguish these remarkable structures: supertall and megatall.

SUPERTALL

"Supertall" skyscrapers rise to more than 300 metres (984 feet) in height.

While only 22 schemes reached this height in the 20th Century, since 2000 the number of buildings over 300 metres either completed or under construction has exceeded 300.

Prominent examples include New York City’s Central Park Tower and 111W57, Taiwan’s Taipei 101 and Melbourne’s Australia 108.

Above: New York's 472-metre Central Park Tower is classified as a supertall. Image by Michael Young.

The proliferation of schemes meeting the criteria for “supertall” has led to the creation of the final and truly exclusive top tier category.

MEGATALL

Skyscrapers that exceed the dizzying height of more than 600 metres (1,969 feet) move into the rarely used “megatall” category.

To date, only a handful of buildings have ever earned this classification including: Saudi Arabia’s 601-metre Abraj al Bait Tower; China’s 632-metre Shanghai Tower; Malaysia's Merdeka 118 and, the world’s current tallest building; the United Arab Emirates’ 828-metre Burj Khalifa.

Above: Malaysia's Merdeka 118 during construction. Below: The B1M's Fred Mills visiting the top of the Merdeka 118's megatall construction site.

You can learn more about the different skyscraper categories in this video.

Despite a clear ranking system, the never-ending competition to build tall still contends with shades of grey.

Architects and developers around the world have found themselves facing accusations of foul play by using masts, spires and elaborate pinnacles to boost the height of their buildings and claim titles or accolades in certain cities.

There's still some controversy around Merdeka 118 as it overtook Shanghai Tower by virtue of a 144-metre spire. Shanghai Tower has higher useable floor space.

The roof line of New York's Central Park Tower is taller than that of One World Trade Center, but the latter remains the city's tallest building because of its spire.

While CTBUH have outlined new guidelines, the debate around where we actually measure our buildings to still rumbles on.

Learn more about this debate in the video below.

To get more on the world’s most impressive skyscrapers make sure you’re subscribed to The B1M’s award-winning YouTube channel.