This Hole Should've Been America's Tallest Skyscraper

- Youtube Views 1,122,879 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills.

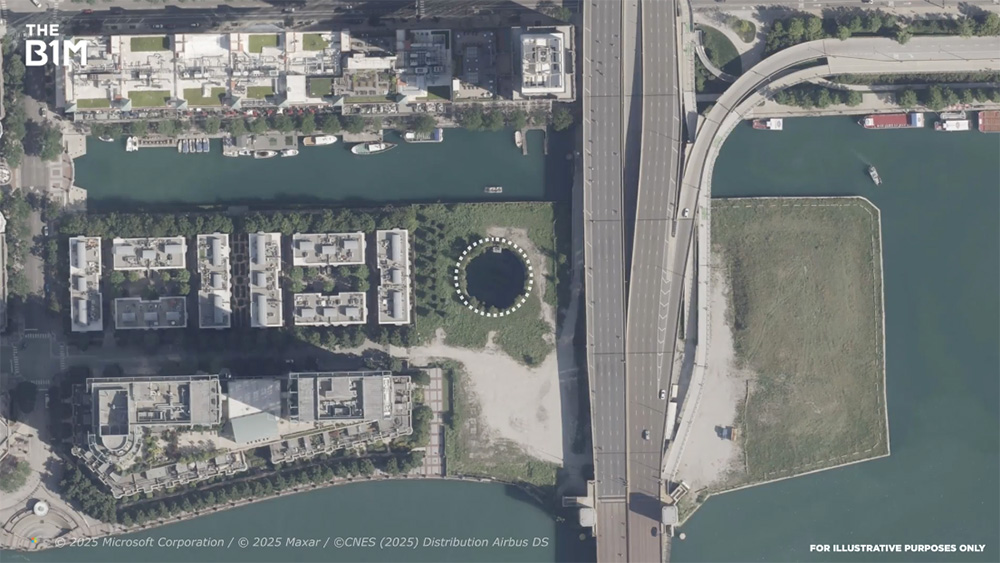

IF you’ve travelled along Chicago’s famous Lake Shore Drive at any point in the last few years you may have seen a strange sight.

Right where the expressway skirting Lake Michigan crosses the Chicago River, a huge, gaping hole has been sitting there, virtually unchanged, for well over a decade.

It was supposed to be the start of America’s first megatall skyscraper, designed by one of the world’s leading architects. But a giant pit is all that remains. A bit of an embarrassment for a city that’s widely considered the birthplace of the skyscraper.

But a decade and a half later, something has changed. The hole has been filled and in its place an actual building is taking shape.

Fight for the skies

Chicago has a history of tall building rivalries. Even now, people still debate whether this city, or New York, is the true home of the skyscraper.

Back in 2005, a new battle was heating up — but this one was to be fought within Chicago’s boundaries. Donald Trump had just seen construction begin on his giant International Hotel & Tower — a building that would become the city’s second tallest when it was completed four years later.

Only the iconic Willis Tower — or Sears Tower, if you prefer — which took the title of world’s tallest building in 1973, had a greater height.

However, plans were being drawn up for another mega-structure that would break records again, and give America its first ever megatall skyscraper.

Not only that, at 610-metres and 150 storeys it would have just the Burj Khalifa above it in the global rankings once it finished in 2012.

Initially named the Fordham Spire after the real estate developer, the building featured a striking design from Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava.

With a majestic twisting form that makes the facade look as though it’s moving, the tower would — at first — offer a mix of condos, a hotel and a broadcast antenna.

And yet, the Fordham name was to be short-lived. Just months into the project, the firm was unable to generate enough funding.

In stepped Garrett Kelleher of Dublin-based Shelbourne Development to take over, stating he would provide 100% of the equity.

Above: A rendering of the Chicago Spire. Image courtesy of Santiago Calatrava.

After gaining control, Kelleher considered renaming it according to the location — 400 North Lake Shore Drive.

But in the end, he decided on a tweak to the original. From then on it would be known as simply the Chicago Spire and consist of luxury apartments alone — over 1,000 of them.

By mid-2007, work was ready to begin on a building that had been unanimously approved by the Chicago Plan Commission, the city’s zoning committee and the council.

Not everyone was in favour of it, though, including Trump. Years earlier, he said: “I would not want to build that building. Nor would I want to live in that building. Any bank that would put up money to build a building like that would be insane.”

Unperturbed by the future president’s stern words, construction got underway in June that year. Like all skyscrapers, the foundations had to go in first, which took the form of — you guessed it — a big round hole supported by caissons buried deep in the ground.

Inside this, the tower’s circular core would be built, with the helical floor plate cantilevering out from the centre. Each floor would be offset from the one below by just over two degrees, giving the building that twisty shape.

But it never got that far. Before any more could be done on the rest of the build, it was 2008 and we all know what happened then.

The Great Recession hit the project hard, causing all building work to be suspended. Anglo Irish Bank, where most of the money was being borrowed from, was close to collapse, with Shelbourne facing lawsuits, and it turned out Calatrava was owed millions.

What was so far little more than a massive crater — over 20 metres deep — in one of the most valuable areas of Chicago, went no further. This literal scar on the landscape would stay here, seemingly untouched, for more than 15 years.

Making a move

However, while it appeared nothing was happening, plans to put something new there were being drawn up behind the scenes.

In 2014, the site was acquired by Related Midwest, the Chicago branch of the development company known for New York’s Hudson Yards, the Grand LA in Los Angeles and the transformation of London’s King’s Cross.

Their first point of order was to put a stop to speculation the Spire might be revived. Instead, they decided to take a completely new approach with a proposal announced four years later.

Above: The Chicago Spire foundation hole alongside Lake Shore Drive.

Rather than one huge tower, this spot of land would be home to two skyscrapers, but not megatalls. That would be … excessive.

No, these were considerably smaller — one rising to 335 metres, featuring hotel rooms and condos, and the other reaching 260 metres, offering rental apartments only.

Architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) was brought in this time, led by David Childs, who designed the actual tallest building in America, One World Trade Center. It would be Childs’ last project before his death in March 2025 at the age of 83.

SOM’s vision is to have the two towers set slightly apart from each other and at different angles, tapering from base to tip and angling back towards the cityscape.

This will create a new visual gateway to Chicago, ensuring views from the west are interrupted as little as possible.

“From a design and skyline standpoint, we thought that a gateway was an appropriate and powerful analogy and metaphor for this site in particular — this being the site of the founding of the city of Chicago,” explained Scott Duncan, design partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

“This is where the river meets Lake Michigan, and it was understood to be the place where the very early settlers came to found the city itself.”

Water features

Meanwhile, at ground level, a new park is being built that will connect up with Chicago’s famous Riverwalk.

There’s metal detailing inspired by the rippling surface of the lake and the famous ‘Chicago Window’ — a hallmark of the city’s architectural history — has been incorporated into the design too.

But like with the Spire, some major revisions were required before the project could proceed. Just months after they were put forward, alderman Brendan Reilly put the plans on hold. His demands included the removal of all hotel rooms, and a smaller podium between the two towers.

Back they went to the drawing board, returning with a design that offered some noticeable differences.

Height was the most obvious one. The South Tower had shrunk significantly — now measuring 233 metres — while the North one had actually grown slightly — to 266 metres.

“There were hundreds of variants of this design that were explored through the process. And that was done for a variety of reasons — notably, we're exploring different ways in which the rates of change of stepping could impact wind forces, for example,” said Duncan.

“Another is that the types of units, the sizes of the homes here — the residences — is something during the design process that's in constant flux.”

The previous (above) and current (below) designs for 400 Lake Shore. Images courtesy of Related Midwest + Noe & Associates/Boundary.

Approval was given in 2020, but that’s another year we all remember for the wrong reasons. Along came COVID-19, stopping the project from making any further progress for years.

Until 2024, when construction was able to begin on Phase One of the project. That’s the first of the two towers — the taller one — comprising 635 rental apartments. 20% of them are expected to be affordable housing. And all of this would be built right inside that big old hole.

Filling the hole

OK, but what was the method here? How do you go about reusing an excavation for what was to be a much larger building?

“Many questions arose about how would we navigate what was left in the ground? And how would we be able to benefit from what was left?” said Don Biernacki, executive vice president at Related Midwest and president of LR Contracting Company.

That’s the general contractor for the project, alongside BOWA Construction. Together, they had to work out how to tackle the various obstacles around the hole — or the cofferdam, to give it its proper name — and remove what was inside.

“There were roughly three million gallons of water that was pumped out of the cofferdam, [and] there was a CSO line running through that site, so that had to be relocated,” added Nosa Ehimwenman, CEO of BOWA Construction.

Once this had been done, more than 600,000 pounds of steel was brought to the site — equivalent to around 150 cars.

Next, 250 trucks descended on the hole and began pouring concrete into it, with the steel acting as reinforcement. A delivery was made every two minutes on average for 12 hours straight.

In total, nine million pounds — around 4,000 tonnes — of the material was supplied for what’s called the mat — or raft — foundation.

It’s where a single, thick floor slab is placed onto soil — or in this case the bottom of the hole — and its job is to carry the load of the structure above, and distribute it over an area.

Using what was already there didn’t just save all the effort of digging a new excavation. Construction teams could also recycle the piles, or caissons, that stretch from the base of the hole all the way down to the bedrock, which were built for the Spire all those years ago.

“We were able to reuse a lot of those caissons. We had to relocate some of them, some were reused and some were abandoned,” said Ehimwenman.

“Then you're building around existing townhomes, there are condos adjacent to the site. We're getting materials in, concrete trucks and things coming in and out. A lot of coordination needed to happen as well.”

Above: Concrete trucks lining up outside the hole. Image courtesy of Related Midwest.

After the foundation was finished, teams started building the core of the new tower in the middle of the hole. At the same time, the space around the core was gradually backfilled with material gathered from nearby.

“We actually used and started to dig some of the excavation around the cofferdam so that we could use the sand that was available to fill the hole,” Biernacki recalled.

“So, as we would come up we would fill it and then we would start to do the formwork and the foundation systems for what would ultimately be the core of the building.”

When the structure had exceeded ground level, in went another layer of concrete and all of a sudden Chicago’s biggest eyesore was no more.

After that, it became a fairly typical skyscraper construction site, with construction crews now focused on building the tower’s 72 storeys piece by piece.

And they’ve been going about it in quick fashion. By April 2025 a new concrete floor was being poured every three days, and almost a third of the final total had been completed.

While all of this is going on, a second team follows close behind. Their job is to install the glass curtain wall, which is key to enabling that distinctive architectural window design.

Looking ahead

Unless there’s another global financial crash or pandemic on the way — and you never know these days — this project looks to be nicely on course.

The first occupants are expected in 2027, and as for the south tower, work on that won’t begin until this one is fully built and occupied. So, putting a precise start on that is difficult.

“We'll have to look at market conditions at the time and make that assessment. But there is a complete commitment by the team here at Related that that second tower certainly brings completeness to this site,” stated Biernacki.

Above: The new tower rising high above the site earlier in 2025. Image courtesy of Related Midwest.

The Spire is far from the only skyscraper to be stopped midway through construction, but the fact that its remnants were left exposed for so long is not what you’d expect from a city like Chicago.

Still, that’s all in the past now and the hole is gone, with the Spire’s successor moving along steadily. While some will be disappointed the original plan never came to fruition, this replacement can be seen as a reality check in a world where buildings this tall are few and far between.

Chicagoans will no longer have to be reminded of that monumental failure every time they make this journey. Instead, they’ll be able to admire two buildings that might not be quite as extraordinary as what could have been, but do far more than just plug a gap in one of the world’s most famous skylines.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Related Midwest, Santiago Calatrava, Skidmore Owings & Merrill, ABC 7 Chicago, Adam Fackelman, Airam Dato-on, Building Up Chicago, CBS, Daniel Schwen / CC BY-SA 4.0, J. Crocker, John Delano of Hammond Indiana, Marc Buehler / CC BY-NC 2.0, Milkomede / CC BY-SA 4.0 and Voice of America.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.