Inside Europe’s New Mega-Tunnel Under The Alps

- Youtube Views 2,205,199 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Straight Arrow News.

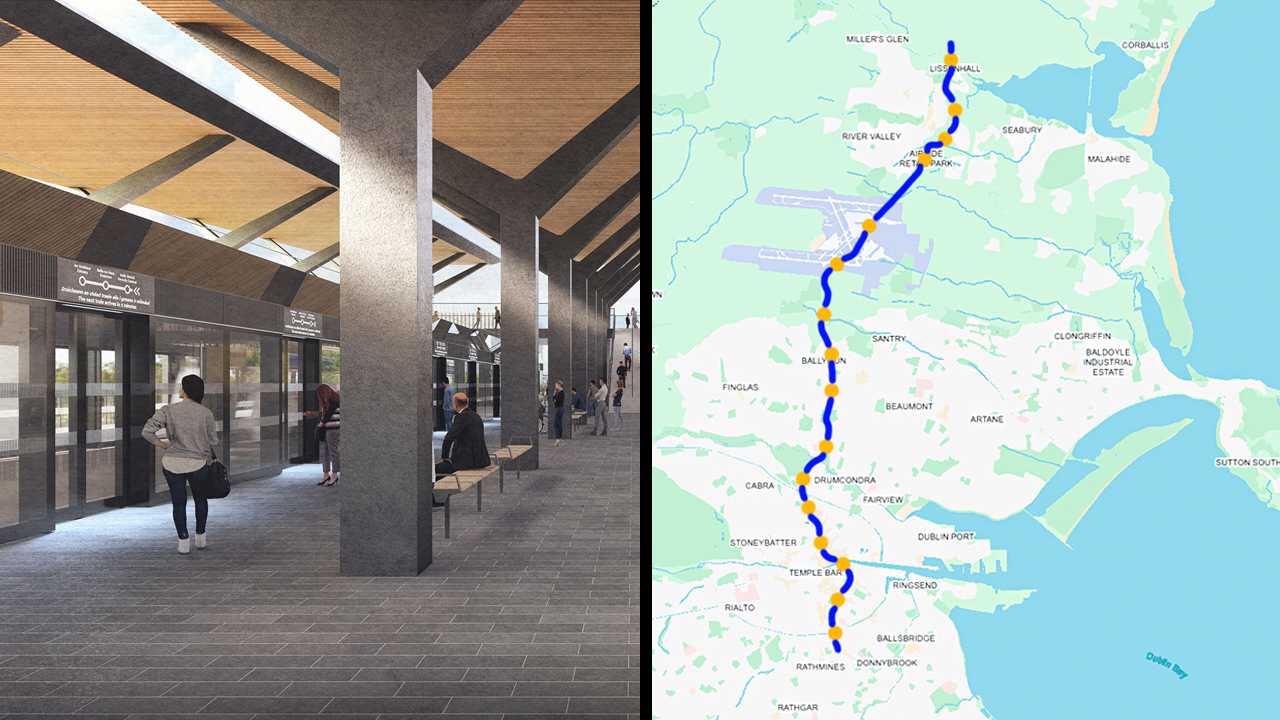

IF you were to take a trip from Lyon in France to Turin in Italy, the chances are you'd take the car. But it's not a straightforward journey because sitting in between these to cities are the might Alps.

Although it's a beautiful drive, it'll take you about four hours, and it would be about the same if you were to go by train.

However, it's not going to start that for much longer because construction teams are now working on a new railway underneath this natural border, and they're doing it with a record-breaking tunnel.

Next-door neighbours

France and Italy are two of the largest economies on the planet, and they're situated right next to each other.

But despite that, and the fact they're both part of the EU, moving people and goods between them isn't exactly easy.

And it's because of those mountains. It's a difficult place to build a road, let alone a railway, which is why 92% of all freight movement between Italy and France through the Alps is done by truck.

Going by train means travelling on a line that was built in the 1800s and is nowhere near high speed because it's full of winding curves and steep slopes.

Not to mention the landslides, which are a very real threat here. The one that happened in 2023 was so severe it caused the whole railway to shut down for a year and a half.

Above: The Alps make moving between France and Italy harder than you might expect.

Obviously, the way we build our railways has changed massively since the 19th century. Trains today are not just faster, safer and more comfortable, but they can get across difficult terrain that just wouldn't have been possible all those years ago.

A lot of it is down to new tunnelling techniques, but here in the Alps, engineers have been perfecting an approach that takes underground construction to a whole new level.

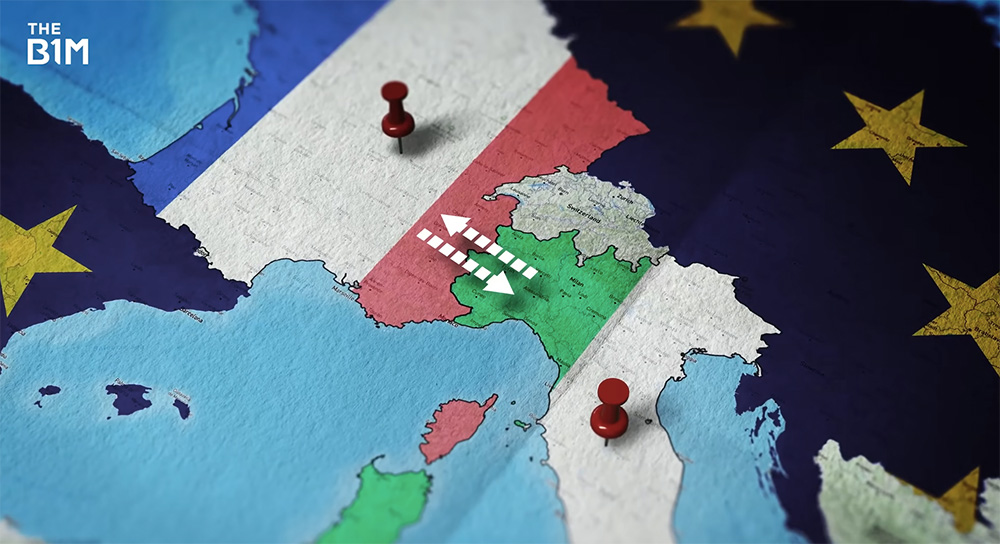

They're called base tunnels, which comes from the fact that they burrow right through the base of a mountain. And that's exactly what's been under construction halfway between Lyon and Turin, across the French-Italian border.

Stretching for 57.5km, it'll become the longest single rail tunnel in the world — a fraction longer than the Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland.

Although that one is almost a decade old, it remains one of the only base tunnels to have been completed on this planet.

Fast track

Thanks to the Mont Canis Base Tunnel as it's known, travel times between the two cities are going to be cut from three hours and 47 minutes down to just one hour 47 minutes.

It's not just about speed, of course. Once the new railway is complete, driving will no longer be the best way to get from A to B.

Those road and rail movements are expected to become a lot more balanced — quite literally 50-50.

It'll take around a million heavy vehicles off the road every year, or at least that's the aim. If achieved, it would mean an annual reduction of a million tonnes of CO2, which is roughly the same as what 400,000 homes produce every 12 months.

Freight trains are going to be able to carry 2,000 tonnes instead of 700 like they can now, and for passengers, there are going to be 22 long distance rail services every day. That's up from the six there are right now.

Above: With base tunnels, tracks can be laid almost flat, and that enables faster trains and shorter journeys.

France and Italy won't be the only countries to gain from this project. The new line is going to fill a crucial gap in the Mediterranean Corridor of the Trans-European Transport Network.

It's going to make travelling between the east and west of Europe a hell of a lot easier, boosting economic growth and helping sustainability. But before that dream can become a reality, there's a few challenges to overcome.

At the start of the Mont Cenis Base Tunnel, on the French side, trains are going to enter through a rectangular-shaped cut-and-cover tunnel, then come into a 3km section which passes through some particularly tough geology.

Tests revealed that the ground here is full of fractured and sheared rock, which meant they had to do this section the old fashioned way.

We're referring to the traditional tunnelling method, otherwise known as drill and blast. That, as the name suggests, involves drill and blasting your way through the rock.

Bang-up job

It’s quite simple. You basically drill holes in a circle, fill them with explosives, hit a big red button and blow them apart.

Next, you clear the rubble out of the way using trucks, put some steel ribs in to reinforce the rock around you, spray that with shotcrete, which is kind of like a mix of sprayed concrete.

Another thing that's very visible is how wet everything becomes before a section of the tunnel is fully waterproofed. In some places it looks like a lot, but never enough to concern those in charge of the build.

"We face in the Alps water ingress, which is normal. This is not bad for us because we have long distances for the logistics and we like the water on the surface to avoid the dust problems, which is a severe problem for health and safety," said Alexander Heim, project manager at contractor Implenia.

"So basically water is nice for us. The water which is too much, we pump it. We have different pumping systems, we put it out in a treatment plant, we recycle it and we reuse it on the front for the drilling and excavation process."

Above: A view from inside the Mont Cenis Base Tunnel.

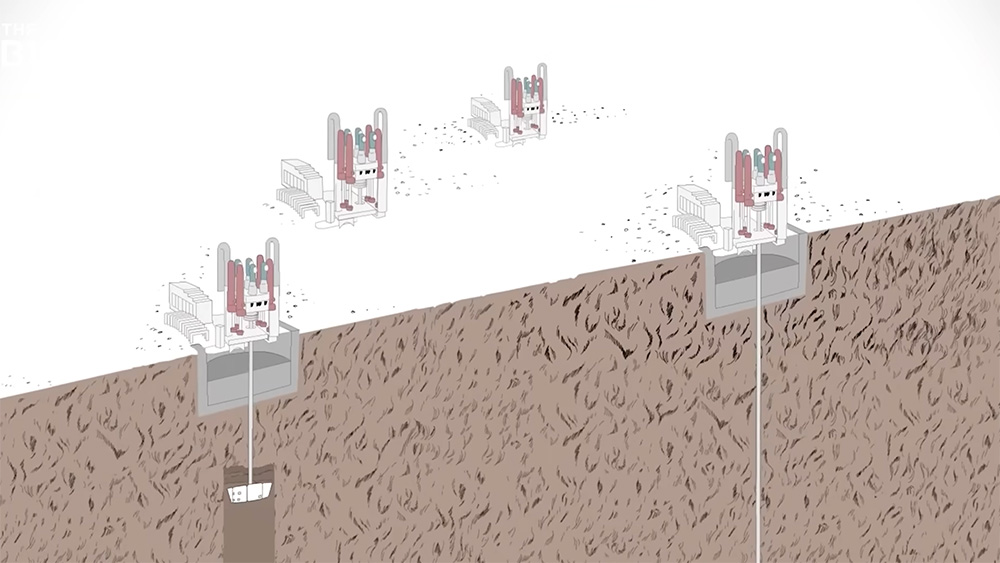

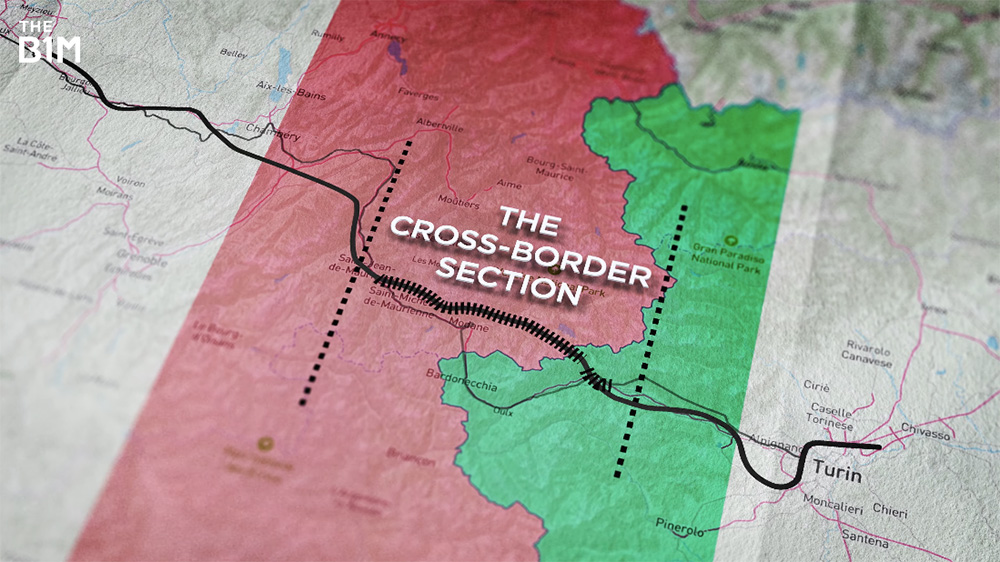

The railway is going to be 270 kilometres long. 70% of it sits in France, and 30% of it sits in Italy. It's divided into three main parts.

There's the cross border section that consists of the main base tunnel and the bits either side that connect to the existing railway.

That part of the project is being overseen by Tunnel European Lyon Turin or TELT. It's the public promoter in charge of the construction and management, with ownership split 50-50 between the French and Italian states.

Then you've got the segments that'll run to the two cities, which include several more tunnels, albeit much, much shorter.

The scale of the task

In total, the cross-border section features 162 kilometres of galleries and tunnels, including access shafts and safety bypasses. Over a quarter of the tunnels — nearly 50 kilometres’ worth — have now been completed.

The base tunnel starts in Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne and ends in Susa. 45 kilometres of it are on French soil — or rather in French soil — and the remaining 12.5 kilometres are in Italy.

And because trains are going to need to travel in both directions, there are actually two tubes, one on the north side and one on the south side.

There's loads to be done, which is why when construction's at its peak, some 4,000 workers are going to be involved in this project across its multiple sites.

Above: Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in France.

So in years to come, if you were to take a train journey from Lyon to Turin, Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne is the last you'd see of France — the last you'd see of daylight — before you headed down and went deep underground.

There's already a pretty big train station here, but it's going to be replaced by a much bigger international one. And it's the same story down at the other end in Italy as well.

A quiet, peaceful valley like this, is going to become home to one of this continent's most important infrastructure projects.

The (not so) boring method

That drill and blast method is only being used to excavate around a quarter of the overall tunnel. Another technique, arguably even more dramatic, is needed for the rest.

In total, seven tunnel boring machines are going to be working away under the Alps at the same time. And one of them, the first of them, called Viviana, began its journey in September 2025.

Its job is to dig a 9km stretch of the overall route. That's the part between Saint Martin-La-Porte and La Praz.

Access tunnels have already been built in both of these locations, so it's now a case of joining them together, which, as you might have guessed, is not as easy as it sounds.

Above: Viviana is a hard rock TBM — 2,000 tonnes in nominal mode, with a 10.4-metre diameter. Half of that weight is at the front. Image courtesy of TELT.

Up at the face of the machine, 61 cutters break up the rock as the machine moves through the mountain. The cutter head is fixed to the section at the front, which is known as the shield.

This was transported into the tunnel at a 90 degree angle to the direction it needed to travel. That meant it had to be rotated before the rest of the TBM could be fully attached.

Laying the foundations

Because it's not all about the bit that does the actual digging. Behind the cutter head, another part of the system lays the concrete segments that form the lining of the tunnel, giving it extra stability.

TELT has set a target to cast 100,000 of these segments, which are 50 centimetres thick and reinforced with rebar. Eight of them form one ring.

Further back still, a series of trailers help carry the excavated soil and rock back to the surface via a conveyor belt.

More than half of that material is being reused on the same project. Some of it in the tunnel linings, but it's also finding its way into railway embankments and the new train stations.

So it does a lot more than just dig a big hole. It's essentially like a giant mobile factory, which is why it requires an entire team to operate it. There are 15 people all working together to run and supervise this machine's various functions.

Above: Excavated material being carried out via the TBM.

Constructing a base tunnel isn't just drilling in parallel lines. The north and south tubes are linked at several points.

Every 333 metres, you'll find a small passage connecting the two sides of the main tunnel.

They'll be used for maintenance and emergency escape routes in case one of the tunnels needs to be evacuated.

But the problem with building such a lengthy tunnel and doing it through the base of a mountain is the uncertain geology.

You might think they would have known from the beginning what kind of soil, rocks, and even fault lines they're going to find as they bore through. But you can never be absolutely certain, even with all of today's tech.

The last thing you want to do Is drill all that way and encounter a major issue that could cause delays, put your teams at risk or even stop the project entirely.

Going exploring

And that's why teams have incredibly spent years digging exploratory tunnels to try and work out what's here before they go ahead and construct the main route. One such tunnel was completed in 2022 to give planners a better idea of what to expect.

"Each moment, each phase of excavation it can present some new surprise," explained Matteo Calorio, a geologist working for TELT.

"We pass 80 different geological domains, so a lot of different types of rocks, from the alluvial deposits at the entrance of the tunnel on the French side, to the gneiss — one of the oldest rocks in the Western Alps. These rocks they have also a different behaviour and response to our excavation."

Above: The tunnel passes through several different rock types.

To give them access to the base tunnel, seven huge caverns up to 22 metres high and 23 metres wide are being excavated.

The next load of TBMs are then going to be assembled inside. Once completed, they'll be tasked with digging the long section from the centre of the tunnel all the way across the Italian border. The first machine that's going to be setting off here quite soon is pretty different from Viviana.

"Basically it's what we call a Gripper TBM. These TBMs are specially designed to mine and to go through hard rock conditions," said Thomas Deviese, tunnel construction manager for Eiffage Génie Civil.

"So there is no precast segment elements like you have on the other project. On this one we are going to mine and depending on the geology, we are going to either shotcrete or install bolts or steel frames to support the ground."

A breath of fresh air

Further down the line is where boring machines have once again been put into action. But these don't look anything like the ones we've already seen.

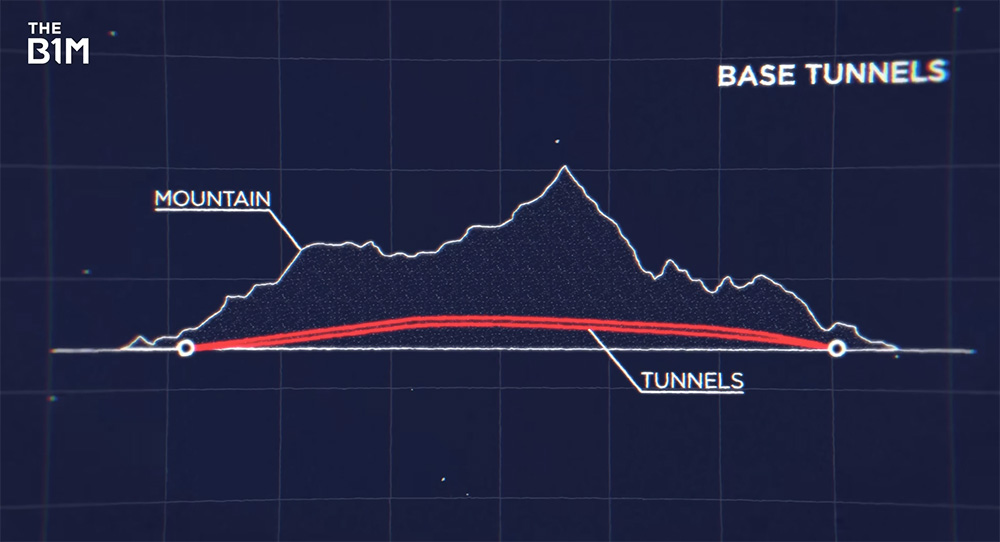

Instead of going sideways across the rugged landscape, these teams have been drilling straight down. Four vertical shafts are under construction which will go all the way from the surface 1,300 metres above sea level to the base tunnel under the mountain.

They provide ventilation, which is especially important when you're tens of kilometres inside a mountain. Without it, the air wouldn't be breathable, either for the people working on the projects or if passengers need to be evacuated once the tunnel's in service.

Above: Raise boring machines are being used to dig the four ventilation shafts halfway down the tunnel. Image courtesy of TELT.

First, a pilot hole, roughly 40 centimetres in diameter, is bored into the ground just big enough for a long metal bar to be slotted in all the way down to the tunnel.

Where cavities occur, a cylindrical metal formwork is placed inside, allowing the gaps to be filled with concrete.

Then a cutting head is attached to the bottom, which is used to excavate back up to the surface. It's a technique borrowed from mining and they're known as raised boring machines, a kind of vertical TBM.

The first of these shafts has already been excavated and covered with a temporary lining using this new type of robot that's placed inside.

Forza Italia

While most of the activity on this project has been happening in France, things have started to ramp up on the Italian side as well.

Preparations are in place for the facilities that will handle the making of the tunnel segments, as well as the processing of the excavated material.

A new junction of the elevated highway in Chiomonte is also in progress, which vehicles are going to use to access the sites.

Above: The new highway junction in Chiomonte. Image courtesy of TELT.

Now, one thing you can’t help but notice with this mega-build is it’s happening in a breathtakingly beautiful, peaceful and serene valley.

But that's not going to be the case for much longer, and because of that, many locals here have been against the railway.

Since the very beginning, the project's faced a backlash from protest groups looking to put a stop to its progress.

2023 saw more than 3,000 demonstrators descend on the area I'm in now, resulting in injuries to both participants and police.

They're unhappy with the environmental damage that they feel the new tunnel will cause, especially as there's already a railway connecting Lyon and Turin.

So, in other words, they feel it's not really needed. That's despite the new line being a lot faster, promising green benefits and having less vulnerability to further landslides.

The price tag

The cost of all this is another sore point for a lot of people. Current estimates put the price tag for the cross-border section at just over 11BN Euros, which is around USD $13BN.

Almost half of that (40%) is being covered by EU funding, while Italy is providing the larger portion of the remaining money — 35% to France's 25%.

It's largely because it's committed more of its funding up front than France has, but also because the Italian side is more complex.

The terrain is tougher, the access routes are tougher, it's genuinely a lot more difficult despite being shorter.

As for the whole railway, it's been predicted to cost approximately 25BN Euros, or $29BN, overall. The sections from Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne to Lyon and Susa to Turin will be paid for by their respective countries, with possible co-financing from the EU of up to 50%.

Above: A map showing the location of the cross-border section.

When you visit here today, you can clearly see that this is a mega-build in full swing. But that hasn't always been the case. There have been delays, opposition from politicians as well as protesters, and financial uncertainty caused by gaps in the budget.

That was until July 2025 when a new document was approved that set out the actions and timetable for the project.

A joint commitment from France, Italy, and the EU, it confirmed the remaining schedule for the base tunnel, which is expected to be commissioned by the end of 2033. It also resulted in all segments of the new railway securing EU funding for the first time.

Long way to go

As for what remains on the schedule, it's a lot. There's almost three-quarters of the tunnelling work still on the to-do list.

There are, of course, several years to go until that target completion date, but in the world of big infrastructure projects, that could roll around fast.

But now that all the civil works contracts for the base tunnel, which are worth several billion Euros have all been awarded, the rate of excavation is set to increase significantly.

"We have awarded all the contracts for the construction parts in France but also in Italy. And we are awarding right now the final global contract for the equipment," said Emmanuel Humbert, TELT's construction director for France.

"So we are now constructing all the civil works and we have to imagine some difficulties that that are on the table about the regulations, about the constraints. There is some construction difficulties of course but there is a human challenge also."

Above: The B1M's Fred Mills (right) with Guillaume Lefrere, site manager for VINCI Construction/Webuild.

One decade from today, this charming alpine region is set to get a lot busier than it's already becoming with the construction work.

By then, we should hopefully know whether sacrificing some of that tranquility so the whole of Europe can prosper was the right call to make.

Like so many big infrastructure projects, there are questions here about its immediate impact and whether or not it's going to be worth it in the long run.

Whatever you think of that, what's undeniable is that this project is going to change our world. And the amazing men and women working deep beneath my feet at the minute are playing a huge part in making that happen.

They're going to bring two huge countries closer together. They're going to cut journey times, they're going to take almost a million trucks off the road, cutting emissions. The impact of this is going to be felt by millions of people far beyond those actually using the tunnel itself.

This project really does speak to the best of construction. It shows what we can achieve and the incredible impact that our work can have.

Most of all, it shows that whenever this industry is confronted with something that feels impossible, we prove the world wrong.

Download the Straight Arrow News app by clicking here https://www.san.com/b1m to stay informed with unbiased, straight facts.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Tunnel Euralpin Lyon Turin (TELT), Euronews, No Comment and VOA.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.