The World's Most Dangerous Tunnel

- Youtube Views 825,105 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

IN late 2023, a new road tunnel under construction in the Indian Himalayas collapsed, trapping 41 workers inside for more than two weeks. It led to one of the most intense rescue operations in recent history.

This emergency was a huge wake-up call. The investigation that followed unearthed multiple failings. Two years later, there was a breakthrough on a rail tunnel in the same region that also came close to tragedy.

From ignoring warning signs to inadequate surveys, India's attempts to build new infrastructure through the world's biggest mountain range have at times been extremely dangerous.

Now the country's begun an even greater challenge — its longest ever tunnel. And once again, they've decided to build it here.

Gods' country

The state of Uttarakhand in India sits in the foothills of the Himalayan mountains. It's an area of breathtaking beauty known as the Land of the Gods. That's because it's home to the Chota Char Dham, a series of Hindu temples and pilgrimage sites.

Millions of pilgrims travel here every year, but let's just say their journeys aren't exactly straightforward. The existing roads are narrow with single lanes. They can become inaccessible in winter and the monsoon season, while more than half of the state is at high risk of landslides.

Which is why a 900km highway project is underway to upgrade these routes and build better connections between the sites.

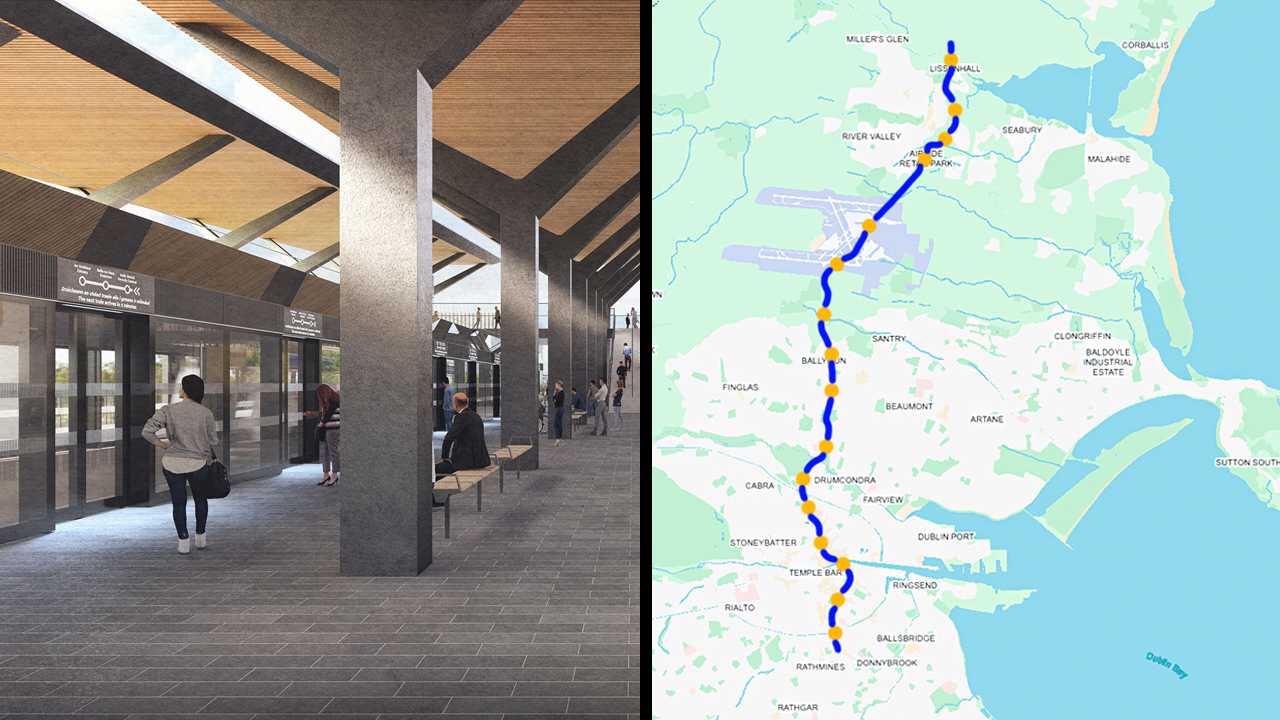

Above: A map of the Char Dham Highway network.

By replacing them with two lane highways and tunnels that can cut through some of the worst spots, travellers are going to be able to take much shorter, safer trips.

Although it's a major piece of new infrastructure and obviously incredibly important to the region and Hindus across India, it's generally not the sort of thing that would make global news.

Until the 12th of November 2023, when the eyes of the world fell on this remote location, around 100 miles from the state capital.

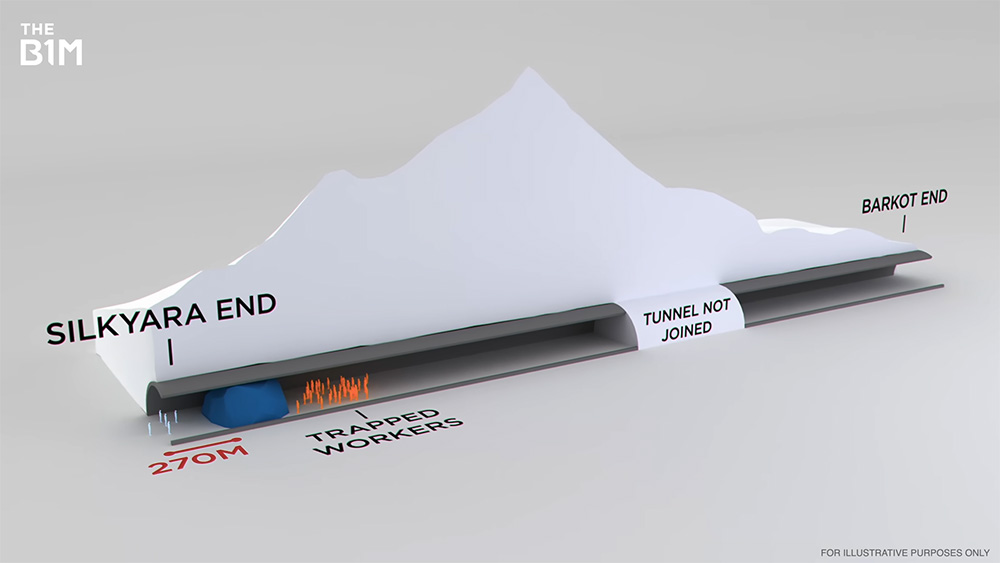

A 4.5km long tunnel under construction as part of the project caved in without warning. Dozens of workers were inside at the time and within an instant found themselves trapped.

They had just one connection to the outside world — a tiny emergency tunnel that provided them with air, food, medical supplies, and water.

The right man for the job

An international expert was called in to help — Professor Arnold Dix. He was, at the time, president of the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association.

Once Arnold arrived at the site and assessed the situation, it was time to create a rescue plan. An auger machine, basically a big drill, was brought in to dig an escape route, but it wasn't the only thing they tried. Several methods were executed simultaneously to increase their chances of success.

“We had a vertical drill coming from the surface down, which is like pushing a pin down through the mountain,” Dix recalled.

“We had a team assessing coming from the back, we had a team launching a TBM from the side and we also had another team working on a very old-fashioned, like, mining solution, hugging the side of the tunnel and bracing it. And we ran all of them concurrently.”

Above: The collapse happened 270 metres from the southern entrance at Silkyara, and because the tunnel had not yet been joined in the middle, the only escape route was blocked.

Eventually, it was the auger that got them out. Well, sort of. It broke down just before reaching the target area.

So a group of miners ended up digging the rest of the way using manual drills, and after 17 terrifying days, the rescuers were able to free everyone in sight.

Now, while it was a huge relief that no one was seriously hurt, this was a real warning sign about the dangers of building infrastructure in this area, and it's not the first sign there's been. Believe it or not, this is not the only tunnel in this area to have come close to disaster.

Near miss

Around 200km to the southeast, another tunnel in the same state, this time for rail, broke through in April 2025. But only after some serious complications.

When the tunnel boring machine reached the 5km point, about a third of the way through, there was a sudden gush of water.

At this moment, according to the project director, the tunnel was at risk of flooding or collapsing. But they managed to correct it by taking corrective measures.

So is it a coincidence that two tunnels under construction so close together either collapsed or came very close to it?

Well, probably not, because it turns out that carrying out this kind of work in these mountains in particular is exceptionally challenging.

Above: A tunnel boring machine used for the new Rishikesh-Karnaprayag rail project, which has had more than its share of challenges. Image courtesy of Herrenknecht.

Firstly, there are shear zones all over the place. That's where an area of highest strain is formed within the surrounding rock caused by tectonic activity.

Tunnelling in areas where they're present can lead to instability, ingress of water or mud, and even collapse.

Then there's the type of rock that's being tunnelled through, which can vary greatly in terms of hardness, and it's not always possible to know exactly what kind of rock you're going to encounter. Another challenge is working with materials that can change the further underground they are.

“Those rocks we see up on the surface, they're not behaving like that once you're deep in a mountain. They're actually behaving like a quite a different substance altogether,” Dix explained.

“I attribute the mountains with a sense of life, I don't see them as, like, dead rock. I actually see them as a living thing because actually they move and they squeeze and they misbehave and they do all sorts of things.”

Could have been avoided

You have to be very careful when digging here, or run the risk of problems like the ones we've seen. Building tunnels in a territory that's prone to earthquakes, floods, and landslides would be a tough job for anyone.

But some of the presumed causes of the collapse were unfortunately man-made. One engineering geologist found evidence of poor workmanship and a lax approach to tunnelling practises.

An official report revealed deformations were not properly addressed, and there was negligence from the contractor towards previous issues.

Above: A view from inside the collapsed tunnel.

And these were plain to see, as Arnold discovered when he first went into the tunnel after the collapse.

“So I've entered the portal and I'm now walking towards where the but while the collapse is still occurring. I count 21 prior collapses. I can see the scars as I'm walking down through the tunnel,” recounted Dix.

“And so I realise this hasn't just happened out of the blue. There's something systemic wrong. No one's thought about changing the method, no one's thought about changing the profile, no one's thought about changing the support system. It was awful.”

They might have experienced difficulties lately, but tunnellers in this country have had some success in the past.

Proof it can be done

India has already built a 9km-long road tunnel in the Himalayas bypassing the notorious Rotang Pass. The Atal Tunnel has cut travel times between the town of Manali and the Lahaul and Spiti Valleys by more than four hours.

But even this had its challenges. It meant digging through a fault zone, and there were points where up to 8,000 litres of water a minute were coming into the tunnel. It all meant they had to be really, really careful. One 600 metre stretch took them four years to get through.

Above: The Atal Tunnel was built at an altitude of over 10,000 feet.

Further to the northwest, in a region that's even more hostile for several reasons, there's another 19 projects in the pipeline.

We're talking about the Union Territories of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir, which have been the subject of disputes between India, Pakistan, and China for decades.

It's an area that's understandably not well connected because building those connections is kind of tricky.

Travelling between these places means taking one of several long winding roads, all of which are pretty treacherous. Like the Zojila Pass, for example. A trip along the worst part of it can take up to four hours.

The ultimate shortcut

Which is why they're now building the Zojila Tunnel. Under construction almost 12,000 feet above sea level, it'll bring that journey time down to just 15 minutes. And because it's subterranean, the road can be used all year round.

So far, there have been no major catastrophes, which could be to do with the tunnelling technique they've chosen.

Above: The Zojila Tunnel is set to be the longest tunnel every built in India, at 13 kilometres. Image courtesy of Megha Engineering + Infrastructures Ltd.

Contractor Mega Engineering and Infrastructures opted for what's called the New Austrian Tunnelling Method.

It's where the strength of the surrounding material is utilised as much as possible, with ground stability monitored continuously. Blasting is involved, but support is provided in the form of rock bolts, steel ribs or mesh, and shotcrete.

If you've never heard of that, it's a type of concrete that's sprayed onto the tunnel walls immediately after excavation. The tunnel is then finished off with a waterproof lining, followed by another layer of concrete.

Now we should clarify here that this method isn't unique to the Zojila Tunnel. In fact, it's been chosen for projects across the region, including on the one that collapsed.

But as Arnold said, being able to adjust the approach as and when problems occur is all part of it, which perhaps wasn't done effectively in the past.

Other tunnelling techniques have been deployed as well, including eight cut and cover tunnels through the more low-lying areas.

These are made by first digging a trench in the ground, constructing the tunnel lining inside, and then backfilling over the top.

Meanwhile, in the main tunnel, three vertical shafts up to 500 metres in height are being placed along it to provide ventilation.

The first has already had a literal breakthrough. A pilot tunnel was successfully completed in July 2025, which will now be gradually enlarged until it reaches the full 7.5 metre diameter.

Although it's now more than 40% complete, this tunnel has had its fair share of obstacles, which explains why the original deadline of December 2026 has now been pushed back by four years.

Light at the end

Back to the Silkyara Tunnel, and 2025 has seen the news take a more positive turn. In April, the two ends finally met in the middle, bringing excavation work to an end. And yet, despite that milestone, there's still a long way to go until it's completely finished.

Still, after what happened, having to wait a little bit longer for it to open is nothing compared to what might have been.

“It's insane. Like I can't believe it's true, but it is true. And we did perform a bit of a miracle, I think,” Dix said.

“I know when I met a lot of the kids afterwards — because they're just kids — I was like, oh my God, we really have given 41 people a second chance at life.”

We've seen tunnels built through similar terrain before without serious incidents. These attempts show us that building infrastructure in the Himalayas is more difficult than many could imagine.

With those calamities now in the past, India must prove that it can tame this unforgiving landscape by taking the stakes even higher. Let's just hope the mountains don't have other ideas.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Megha Engineering + Infrastructures Ltd., ABC7, BBC News, Buddy Sagar, CNN News-18, CTV News, Ex Route Adventures, Herrenknecht, Hindustan Times, India Today, Jatin Chaudhary, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways of India, NEWS9, Shubam Bhasin, The Economic Times, Utkarsh Modgil, Vijay Kothare, Vikash Singh and WION.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.