Austria is Digging a Tunnel Like No Other

- Youtube Views 1,025,489 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This article and video contain paid promotion for PERI Formwork Systems.

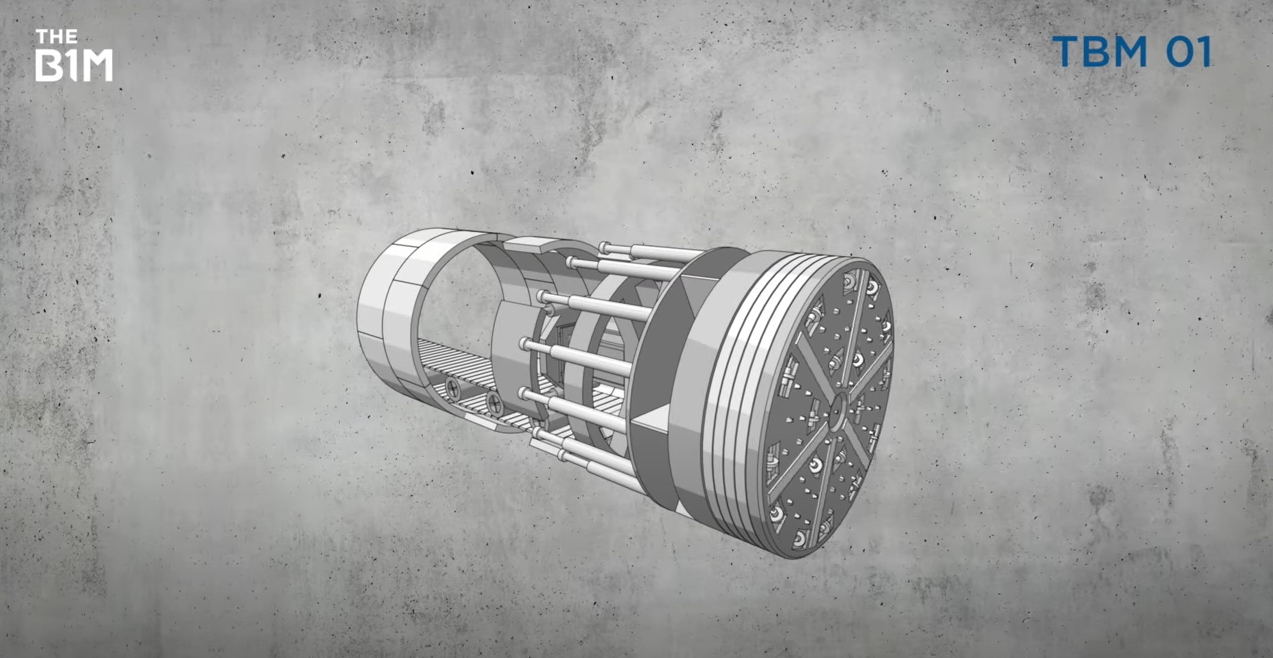

IN LINZ, AUSTRIA brand new tunnels are taking shape deep within the banks of the Danube River.

Soon cars are going to zip through here without realising that this space used to be solid rock. That’s all made possible by one massive 250 tonne piece of kit.

You won’t find this on many construction sites. It’s a one of a kind machine that was built especially for this project, because this isn’t how you’d normally dig.

Crews here are pushing day and night to carve a path that better connects this Austrian city with a massive new suspension bridge. It’s a challenging, twisting and high stakes infrastructure scheme that’s about to impact the lives of millions.

Above: The route of the new tunnels in Linz, Austria.

If you want to get around Linz, you could take a streetcar, cycle, walk or drive. But there aren’t many ways to get across the Danube.

So the city is building a brand new 305-metre-long suspension bridge across it.

But to build above the water, first they have to actually get up there first. And there’s a little problem standing in the way – massive solid rocks along the bank.

So the team in Linz is tunnelling through them to connect the existing highways up to the new bridge. They’re basically trying to build a simple slip road – but inside a massive hillside formed of solid rock and on both sides of the river.

Now here at The B1M we kind of know a thing or two about how to build a tunnel. Time for another quick engineering 101.

First choice for a tunnel nowadays is probably going to be a tunnel boring machine, or TBM.

You know the ones – they’re massive tube-like machines that eat through rock, seal and line the newly formed tunnel with prefabricated concrete segments all in one go.

TBMs are great because they’re efficient and can travel underground without anyone living above really noticing.

Like under ancient woodlands or beneath the city that never sleeps.

But they’re pretty expensive. The nearly 1,000 tonne TBM used on London’s Crossrail cost £10M.

So if you’re splashing out one of those bad boys, you better be getting some serious mileage in.

And since they can be so big – up to 15 metres wide and nearly 200 metres – they’re great for tunnelling long stretches of a relatively straight path.

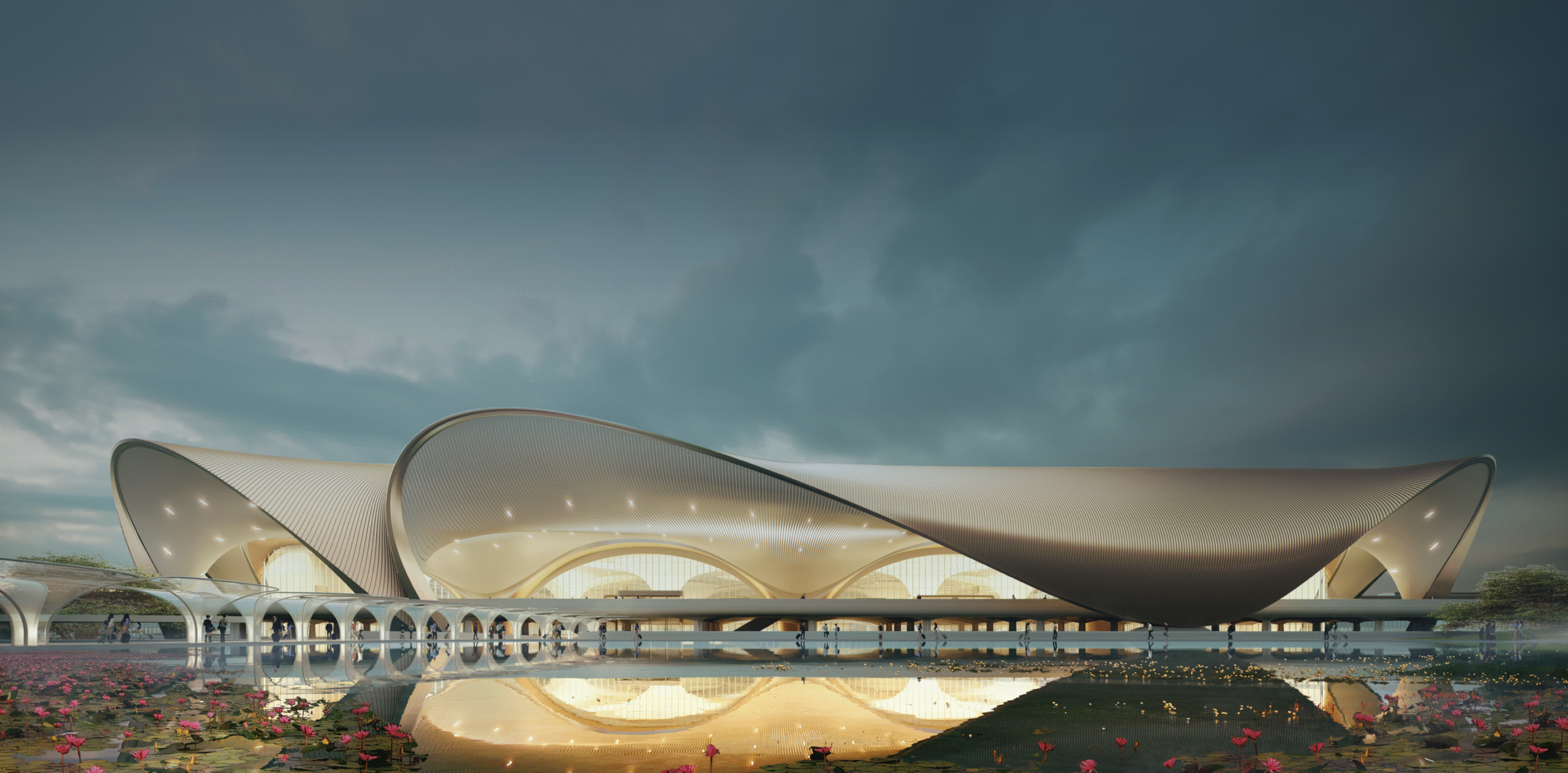

Above: An illustration of a tunnel boring machine.

Sounds like a no brainer for a big infrastructure project, right?

Well yes, but the site in Austria is just 1,600 metres of twists and turns through solid rock along the bank of a river.

So rather than trying to manoeuvre a giant TBM through it, the team used the drill and blast method.

This is the alternative and quite frankly much more fun way to build a tunnel. Granted, it’s not quite so subtle, but it gets the job done.

In incredibly simple terms, you drill some holes in the rock, drop some explosives in, stand very far away, hit a button called “detonate,” clear out the rubble and repeat until you have a tunnel.

The tunnels here in Linz were built using the New Austrian tunnelling method. First the path was cleared using drill and blast, with the debris taken away by boat along the river.

Then a whole load of anchors and drainage points were installed, concrete was sprayed on the walls, and these giant yellow waterproof sheets were added to help seal it off.

But that’s only half the battle. Once the tunnel is cleared the team has to line it to get that nice smooth finish.

That’s where this absolutely massive 250-tonne piece of equipment comes in. Developed by PERI Formwork Systems, the formwork carriage was custom made for this site.

Above: The B1M's Fred Mills stands in front of the formwork carriage on the site in Linz, Austria.

Here’s how it works.

First all the parts of the machine are brought in by truck and assembled.

Then workers first prepare the machine for the day by shrinking it down enough to move through the tunnel. They’ll remove the front bit called the stopend, close the wings, lower it down towards the ground and roll it on through.

Once it’s inside the bit of tunnel that needs to be lined, the wings will expand until they’re very close to the hard rock.

Concrete is then pumped up and through into the space between the formwork and the rock, moulding into the smooth curved shape of the formwork to give the tunnel its nice lining.

Then it’s a waiting game. The concrete needs to cure overnight so the formwork stays in place until the morning when it can safely be shrunk back down and moved forward to the next bit of tunnel that needs to be lined.

Even the slightest delay in the schedule during the day means the concrete won’t be cured by the morning, which means the whole project getting thrown off.

No pressure then.

When it’s at its full length, PERI’s machine can work in 12-metre stretches. But because there are such tight corners to this route, sometimes the team needs to cut the machine in half and pour even smaller 6 metre slivers of concrete to create a curve in the tunnel.

You wouldn’t be able to tell from far away, but if you look up close here you can see that the curve of the tunnel is formed by a bunch of smaller sections fused together to create that angle.

When it completes, millions of people will pass through this tunnel, and the immense effort that went into building it will be taken for granted.

It shows once again the power of construction to shape our world, and the amount of innovation that’s sometimes happening right beneath our feet.

This article and video contain paid promotion for PERI Formwork Systems.

Additional footage courtesy of PERI SE, Mike Wolfsteiner, ASFINAG, HS2, Crossrail and MTA.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.