The Insane Scale of Europe’s New Mega-Tunnel

- Youtube Views 15,109,792 VIDEO VIEWS

Video presented and narrated by Fred Mills.

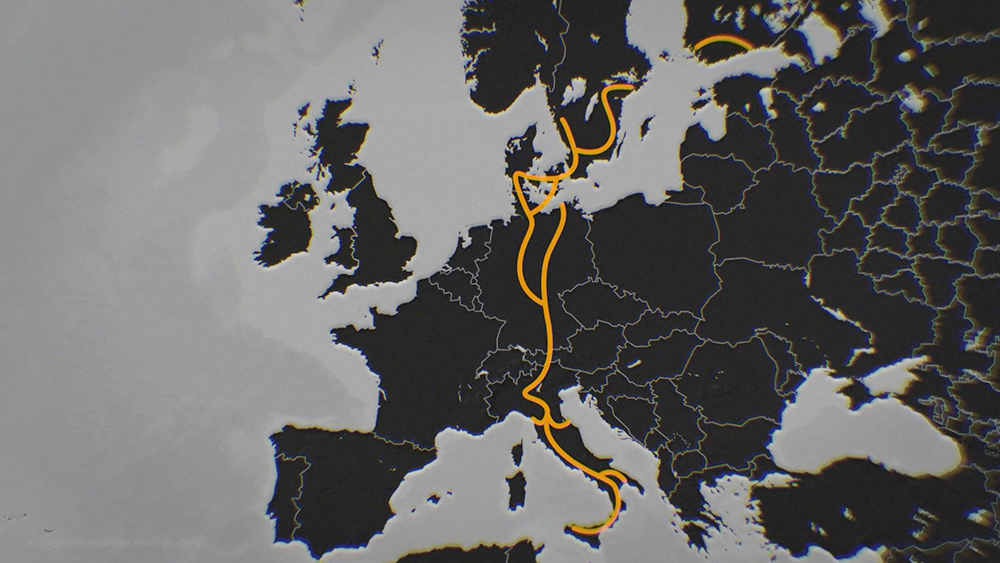

IN A QUIET corner of the Baltic Sea, a sleepy German holiday island is about to be transformed by one of the largest infrastructure projects in the world.

The island of Fehmarn sits just off the mainland of Germany and is separated from the south coast of Denmark by a 20-kilometre stretch of water known as the Fehmarn Belt. Construction is underway on a tunnel between the two countries that will provide the missing link in a transcontinental highway which will move hundreds of thousands of people a year and generate billions of dollars in revenue.

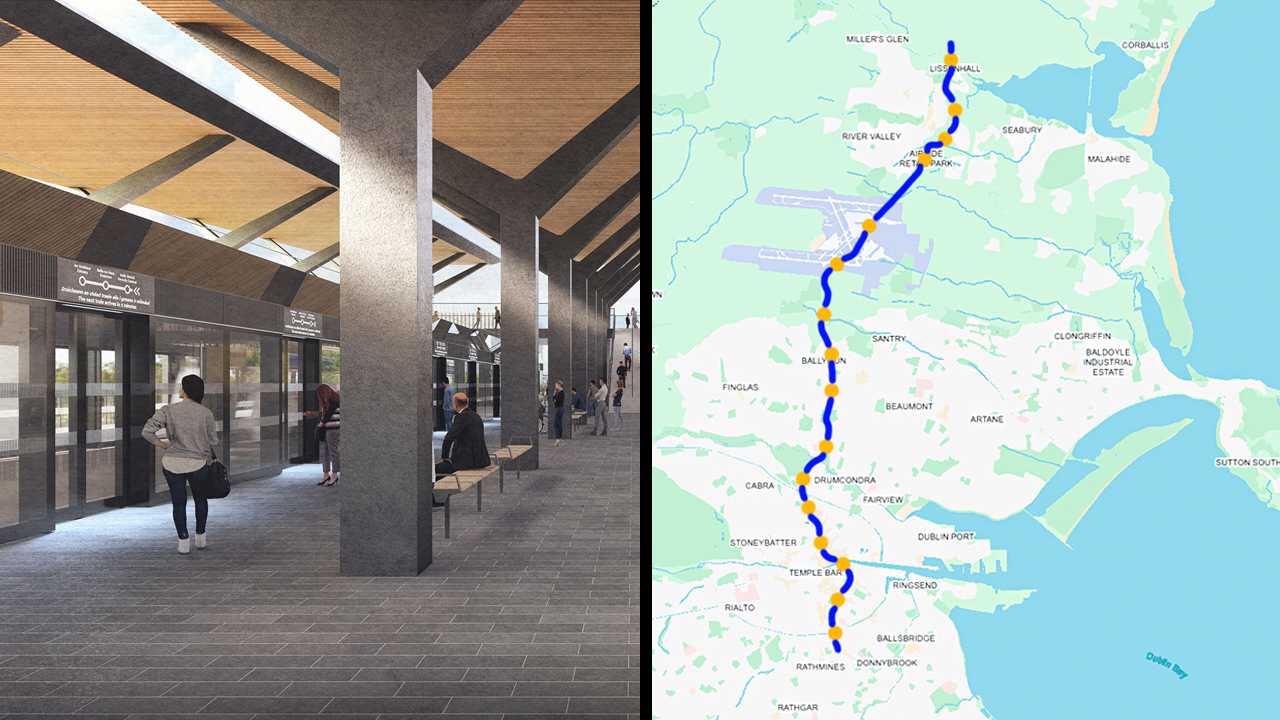

First, let’s take a step back. The Trans-European Transport Network is a series of roads, railways and shipping lanes which connect every corner of the continent. One of the most important routes is the Scan-Med corridor, the central vertical axis of the network which spans 5,000 kilometres from Malta in the mediterranean to Finland's icy tundra.

Above: The Scan-Med Corridor.

Along the way it drills through Alpine rock and crosses frozen seas. But follow the route north through Germany and something strange happens. Instead of driving straight up towards Sweden, you have to take a 150-kilometre loop through the whole of Denmark, and it all comes back to that small, unassuming stretch of water: the Fehmarn Belt.

So, let’s just get this straight. There’s a transport route that stretches from near the African coast to the arctic circle, complete with some of the world’s most iconic engineering – the Brenner Base Tunnel, the Great Belt Bridge – but a small stretch of water in northern Europe is enough to create a detour the size of a country?

Well, it may not look like much but the Fehmarn Belt has thwarted some of the world’s best engineers for over a century. Until now.

The Øresund Bridge is one of those rare feats of civic construction: a mega structure whose architecture and engineering come together in perfect harmony to create a truly iconic piece of infrastructure. Immortalised in the 2011 drama The Bridge, it connects Denmark with the southern Swedish city of Malmö and it was while this crossing was being planned that Sweden had a big idea.

Above: The Øresund Bridge.

Right now to get from Sweden down into Central Europe, you catch a train at Malmö. That takes you over the Øresund crossing to Copenhagen where you change onto another train that takes you down into Hamburg in Germany. Even on a high speed train that takes about five and a half hours, and for a freight train it’s even slower. Germany is Sweden’s second biggest export market, so that’s a huge deal.

The Swedish government saw a shortcut at the Fehmarn Belt so during negotiations with Denmark a deal was struck: the Swedes would help build the Øresund Bridge if Denmark agreed to look into constructing a fixed link at the Fehmarn Belt. Fortunately, that wasn’t as outrageous as you might think.

There’s been talk of creating a railway between Hamburg and Copenhagen since the 19th century – quaintly dubbed the Vogelfluglinie, or bird flight line – but nothing really happened until the 60s when a bridge was built to cross the short stretch of water between Fehmarn and mainland Germany, known as Fehmarn Sound. That route was then extended to a new ferry port at Puttgarden bringing trains right up to the water's edge.

Amazingly the trains were then loaded onto ferries and carried over the Fehmarn Belt and onto to Denmark. The whole thing was pretty slow. The diesel trains that served the route weren’t as fast as the trains we have today, and the ferry itself took over 45 minutes.

Above: Trains on the ferry crossing the Fehmarn Belt. Image courtesy of Smiley.toerist.

For years afterwards there was talk about upgrading the route to a fixed link but it wasn’t until Sweden threw down the gauntlet that things got really serious and in 2008 the Danish and German governments signed a treaty to start work on The Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link.

The proposed crossing would consist of a four-lane motorway and two rail lines serving both freight and high speed passenger trains. The whole thing would be funded by Denmark who would in turn collect the toll fares and run the onshore businesses.

Separately, Germany would upgrade the route from Fehmarn into the mainland to allow for the new trains and traffic to pass through, which would include building another short tunnel to cross the Fehmarn Sound.

It would be a once in a generation upgrade in the transport network. The Hamburg to Copenhagen corridor would be transformed into a high-speed road and rail route, the Swedes would get their shortcut to the continent, a massive detour would be wiped off the Scan-Med corridor and that, in turn, would transform the wider Trans-European Transport Network. The only thing that stood in the way was the water.

The most obvious solution was a bridge. Feasibility studies had been conducted as far back as the 90s and – as proved by the Øresund crossing – Denmark was pretty good at building them.

The proposal they came up with was a three-kilometre long, cable-stayed bridge sitting about 65 metres above the water so that ships could still pass underneath.

The cable-stayed design was similar to the Øresund Bridge but with one key difference, it would be three times as long – and that’s where the problems began. It may not be a wild, perilous ocean but the Fehmarn Belt is still pretty awkward. It’s just under 20 kilometres wide, surprisingly deep in places and the soil conditions aren’t great for building on.

Above: The proposed Fehmarn Belt Bridge. Image courtesy of Dissing+Weitling / Femern A/S.

To contend with the length of the Fehmarn Belt the bridge would have needed spans of over 700 metres, longer than anything which has ever been built for a combined road and rail bridge.

The plan was to construct three huge pylons each just under 300 metres tall. The foundations of those would have to be built at sea in depths of up to 25 metres. Throw in poor soil conditions and a busy shipping lane and you have an engineer’s idea of hell.

After careful consideration of the risk of cost overruns and the technical complexity of construction, the bridge was firmly ruled out. So, if you can’t go over, you’ve got to go under. No problem there though because the Fehmarn Belt is the ideal length for a bored tunnel.

There’s a few reasons why bored tunnels are great. First off they don’t disturb anything above ground. That’s why they’re usually used for underground railways in cities but that’s also great for a place like Fehmarn which has a delicate ecosystem that could take years to recover from all the disruption caused by building a bridge.

They’re expensive but they tend to be more economical the further you go. So the team set out to investigate the possibility of a bored tunnel under the Fehmarn Belt. But that too hit a snag.

Bored tunnels are dug by a tunnel boring machine – or TBM. The width of the tunnel depends on the TBM but something like London’s new Elizabeth line used machines around seven metres wide.

Above: The drill head of a tunnel boring machine.

They’re good for something like an underground railway because you have one track per tunnel. But Fehmarn needs a railway, motorway and an access tunnel. That could mean boring 5 separate tunnels at five times the cost. And that’s not all.

Very little of a train’s surface area actually sits on the track and because the wheels are made of steel, there’s very little traction. On flat tracks that’s great, it’s one of the reasons trains are so fast and efficient. But going uphill becomes a bit more challenging. The average mainline train can drive upwards by 2.5 percent or 1 in 40. Meaning that for every 40 metres of track, the train can move upwards by one metre.

The Fehmarn Belt is about 40 metres deep at its deepest point and any bored tunnel would have to sit at least 10 metres below that. That would make the tunnel incredibly long in order for a train to travel into it, pass under the ocean and pass successfully again up the other side. A shorter tunnel would create a train track that’s incredibly steep and any train probably wouldn’t make it.

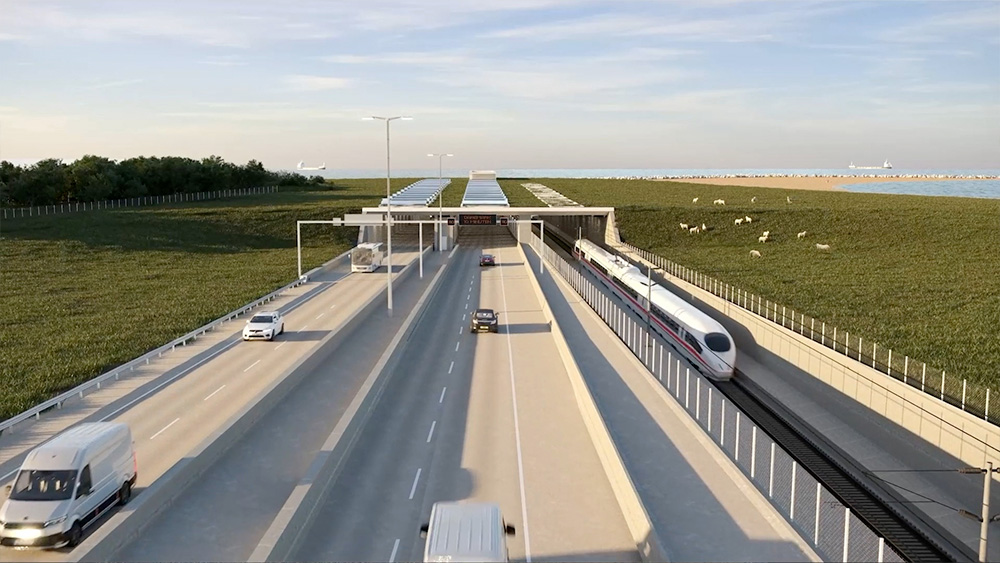

So you may think with a bridge and a bored tunnel ruled out it may be time to throw in the towel. Fortunately, however, there’s one option left: the immersed tube tunnel, or IMT.

Instead of boring through soil, IMTs are made up of prefabricated concrete elements. Once made these are taken out to a trench which is dug in the seabed and sunk and sealed together. Once laid, the whole thing is covered over with earth and hey presto, you have a tunnel.

An IMT is a great solution for a place like the Fehmarn Belt. It’s shallower than a bored tunnel so trains have no problem passing through, as well as being a lot cheaper. You avoid the technical complexities of building a bridge and it poses no risk to shipping once it’s complete.

But as you may expect, there’s a catch. IMTs are usually used for fairly short stretches like rivers and harbours. Keep driving over the Øresund Bridge towards Denmark and you hit a man made island and suddenly drop down under the sea into the Drogden Tunnel. It’s one of the longest IMTs in the world and it’s only four kilometres. The Fehmarn Tunnel will be five times longer.

Above: The Drogden Tunnel. Image courtesy of News Orseund.

So how do you build something that big? Well, it all starts at the immense construction site at Rødbyhavn on the Danish side of the Fehmarn Belt, run by the Danish state owned company Femern A/S. It’s so big, it’s taken them two years just to build the work area.

The star of the show is the enormous factory where the tunnel segments will be constructed. It’s one of the biggest factories ever built in Denmark, altogether covering half a million square metres, around 200 football pitches.

That scale is needed for the production lines that will churn out the 89 concrete tunnel elements, each 220 metres long, 12 metres high and 40 metres wide. Once fully up and running these factories will be on 24 hours a day, seven days a week – for three and a half years.

Above: The Rødbyhavn construction site with the tunnel factory under construction in the centre. Image courtesy of Femern A/S.

When work starts, aggregates and materials will be delivered to the purpose built work harbour and then taken by conveyor belt to the factories where the elements are being cast. Each element is so large it will be constructed of nine smaller segments, each one taking 36 hours to cast.

Once a complete tunnel element is constructed it will get rolled out of the factory and taken to a huge dry dock where it then gets floated and taken out to sea where the tunnel trench is dug.

Massive ballast tanks are flooded to sink the 73,000-tonne concrete tunnel elements to the bottom of the ocean where winches will guide them to within 15mm of their targets. Once all the elements are in place, the trench is back-filled and the tunnel is covered in gravel to protect it, at which point, nature takes over and eventually covers the gravel bed with sand.

Above: An artist’s impression of a tunnel element being taken out to sea. Image courtesy of Femern A/S.

Once the tunnel structure is in place there’s then the small challenge of laying a motorway and railway through it. The tunnel will also be fitted out with ventilation, support and surveillance systems before it’s expected to open for traffic in 2029.

When this tunnel is completed, thousands of cars and hundreds of trains will pass through it every day. The expected economic benefits are huge but it still all costs a lot of money. The budget for the project currently stands at USD $7.5BN. Half a billion dollars of that is coming from EU subsidies, and the rest is coming from a loan by the Danish state meaning it won’t cost Danish taxpayers a penny.

Above: An artist's impression of the tunnel entrance. Image courtesy of Femern A/S.

Denmark actually stands to gain quite a lot from this project. It’s expected that cars are going to be charged around the same as the ferry – around USD $100 for a return journey – which is projected to generate around $4BN in profit during the first 50 years of the tunnel's life.

So, a tunnel which improves infrastructure and creates billions of dollars in profit. What could possibly be the problem? Well it’s not just the Fehmarn Belt’s geography the construction has had to battle. Campaigners from the German Aktionsbündnis gegen eine feste Fehmarnbeltquerung (AGFF) – action group against the Fehmarn Belt fixed link – have fought tooth and nail for the last decade to prevent the construction of any permanent crossing.

This is the downside of massive construction projects. Any new mega scheme has to be built somewhere, whether that’s in a virgin forest, in the middle of a city, or on a quiet German holiday island. Whether you like it or not it’s going to have a massive impact.

One of the key environmental concerns regarding the tunnel is water clouding. Critics of the project argue the soil dredged during the construction will have a significant impact on the ecology of the Fehmarn Belt, as Hendrick Kerlen, chairman of the AGFF, told The B1M:

“The ecology of the Fehmarn Belt is very diverse, it’s marked by a diversity of species which were believed to be extinct in the Baltic. The clouding of the Fehmarn Belt through the release of sediment and the turbidity will reduce the growth of macrophytes and plankton and have repercussions on all fauna and flora.”

Above: A dredging boat digging the trench for the tunnel. Image courtesy of Femern A/S.

Femern A/S says sedimentation is one of the most closely monitored environmental impacts on this project. The company says it uses special dredging machines to minimise the spill and have patrol boats and monitoring stations around the dredging site to collect data on water clouding.

This and other environmental data is published in real time on the Femern A/S website in an effort to improve transparency around the construction.

But it’s not just the marine environment AGFF is concerned about.

A big feature that is being touted about this new tunnel is that it’ll kind of provide a new green link to the continent.

Femern A/S says that because the distance between Hamburg and Copenhagen is being shortened thousands of vehicles will have to drive 150km less. The new rail service will take cargo out of lorries and place them on to freight trains and the new rail link will make taking the train a more attractive option.

But – and this is a big but – constructing something as ambitious as the Fehmarn Tunnel comes with a huge carbon footprint, mostly from the vast amounts of concrete being produced, 2 million tonnes according to Femern A/S’ own calculations.

Above: An artist’s impression of a tunnel element being cast. Image courtesy of Femern A/S.

Femern A/S say once completed, the tunnel will deliver a significant contribution to a green transeuropean traffic corridor by creating a 160 km shortcut, creating a viable alternative to air traffic and shifting goods from trucks to electrified freight trains.

They add that they are making a concerted effort to reduce the CO2 footprint of construction, but it’s not possible to build in this scale without causing some emissions. One of these initiatives is their commitment to use 100 percent renewable energy sources for construction and operations of the tunnel.

Infrastructure inevitably comes into contact with the natural world. That doesn’t mean concerns should be brushed aside but it also doesn’t mean we should never build infrastructure ever again.

What opposition groups such as the AGFF express are legitimate anxieties from people living on the doorstep of one of Europe’s biggest construction projects.

When there is a good case for a new megaproject, it’s important that project teams listen to concerns and work to reduce the impact of their work on people's lives and the environment as much as possible.

That’s something this project has set out to do from the start. Most of the construction activity is being done on the less-populated Danish side of the water and new habitats are being built to compensate for land now occupied by the factory.

Over the next decade a new route will be tattooed onto this part of the map – and for the people who use it, its convenience will erase any memory of the enormous effort that it took to make it happen.

For an example of how this can happen you don't need to travel any further than the southern end of the Fehmarn. The bridge which connects the island to the German mainland was heavily opposed when it was built in 1963 as residents worried it would destroy the place’s unique character. Today it’s considered iconic and there is a campaign to save it, following fears it will fall into disrepair once the new tunnel opens.

Above: The Fehmarn Sound Bridge.

That, in a nutshell, is the story of modern infrastructure. While these projects are difficult and controversial to realise when they’re first constructed they go on to have a defining impact on all of our lives.

The new tunnel under the Fehmarn Belt will impact millions of people across this continent over the decades to come. Any of the controversies around its construction will likely be forgotten and the extraordinary engineering that went in will be taken for granted, as Femern A/S technical director Jens Ole Kaslund said.

“My hope is just that a year after it opens, no one can remember that it was not there."

Additional footage courtesy of Femern A/S, TV2 ØST, NDR, DW, Dissing+Weitling, Crossrail, BBT Clips, Microsoft Flight Simulator and Smiley.toerist.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.