Why No One Likes South America’s Tallest Skyscraper

- Youtube Views 622,164 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted and narrated by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Odoo.

WHAT'S unusual about Gran Torre? It’s a stunning facade of steel and glass, stretching high towards the clouds. At 300m tall, it would easily be at home in New York, London or Shanghai.

However, when you compare it to skyscrapers around the world, it doesn’t necessarily stand out but that’s just it - Gran Torre isn’t in any of those cities.

It’s in Santiago, the capital of Chile and its impact on the people who live there is arguably more staggering than any other skyscraper, in any other city on the planet. That's because Gran Torre isn’t just the first supertall in the country, it’s the tallest skyscraper anywhere on the continent.

But it’s not exactly popular in Santiago. In fact, Gran Torre might just be the most contentious skyscraper in South America.

Above: Gran Torre is the tallest skyscraper in South America and the continent's first supertall.

Welcome to Santiago

Santiago has about everything you could want from a city break. It’s right in the middle of Chile and if you head just an hour to the west, you’ll hit the Pacific Coast. Back the other way to the east is the beautifully imposing Andes mountain range but this city is a lot more than a stopover on your way to ski or surf.

It’s the nation’s cultural hub, blending finance and politics with rich history. Stretching back for centuries, the people here have taken great pride in the country’s architecture.

Santiago was founded on indigenous settlements way back in 1541 by the Spanish conquistador, Pedro de Valdivia. Over the following three hundred or so years, the landscape was shaped by colonial architecture.

Look around today and you’ll see charming, short houses, tiled roofs and patios in abundance. A neoclassical era followed in the 1800s as Chile gained independence and went through somewhat of an economic and cultural revolution - you can still see that architectural stamp in Santiago today.

Above: Santiago has a rich architectural history, a source of pride for the nation.

But that strong bond with beautiful architecture came to a pretty abrupt stop. In 1973, a military dictatorship took hold, lasting for nearly 20 years. It was a period of brutality and repression that saw the country’s architects and designers stifled.

Jump to today and Santiago’s in an age of glass facades and urban development and so brings us to Gran Torre, nicknamed the Mordor of Santiago.

The Mordor of Santiago

It’s meant to be for Santiago what the Eiffel Tower is for Paris, or so its owner Horst Paulmann reportedly said and if by that he meant a controversial tower that divides a nation, then mission accomplished.

"It aligns to how our economy has developed over the last 30 or 40 years", said architect and writer, Nicolás Valencia. "On one side, it shows an idea of ‘this is what we are’ but also, is this the best approach to design a building? People were afraid of how the building would react to earthquakes and how the district would change based on this huge influx of people."

Construction started back in 2006 and saw this building climb higher than any other had before it here and while its architect, César Pelli said it was never planned to compete with the power of the Andes, its impact on the city is like that of a mountain.

Gran Torre dwarfs the city of Santiago, supposedly casting a one mile long shadow - far from ideal if you’re one of the buildings under which it looms.

Above: Gran Torre reportedly casts a one mile long shadow over the city.

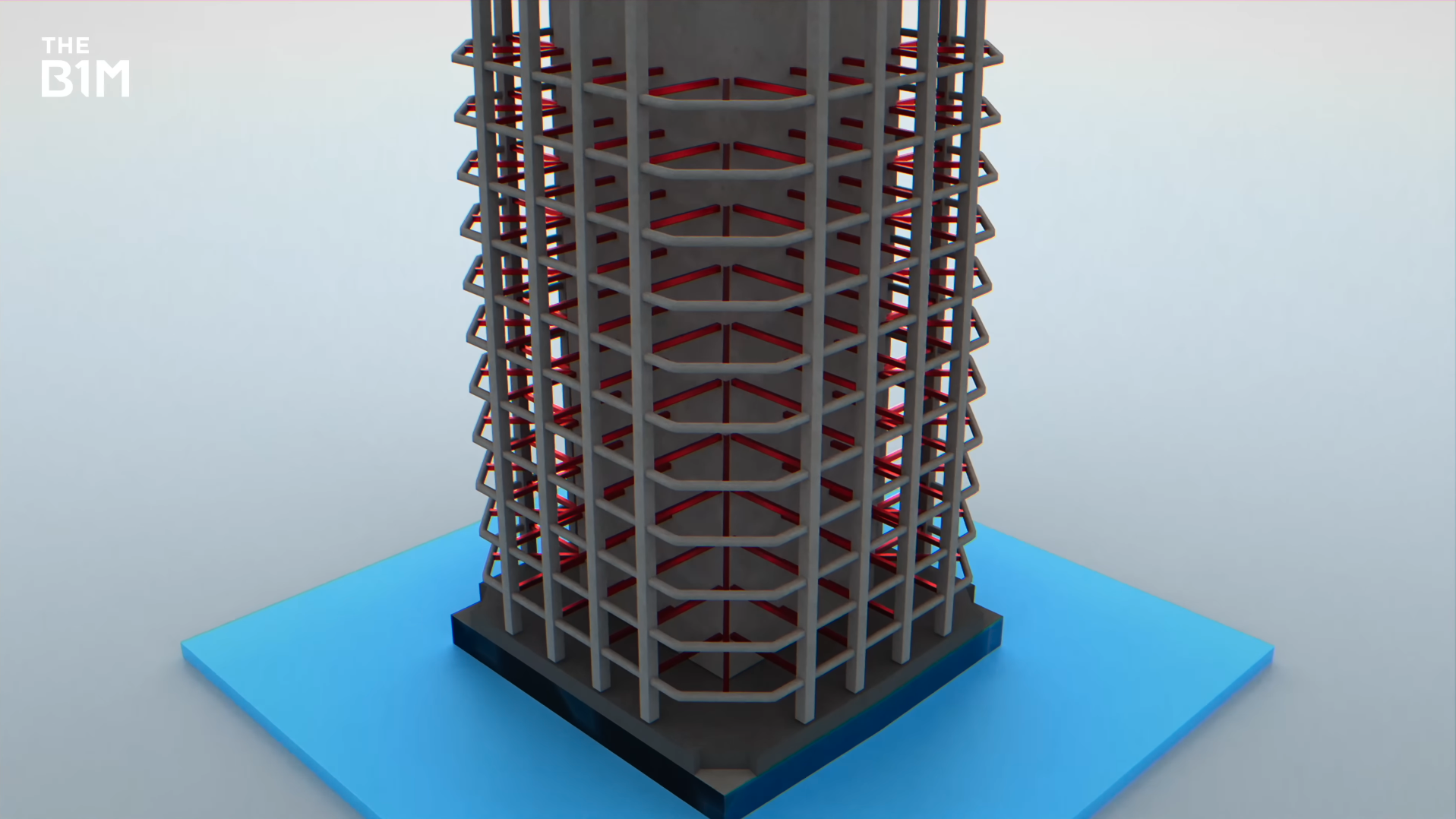

Around 72,000 cubic metres of concrete and more than 18,000 tonnes of steel make up South America’s tallest tower. The body of the structure is supported by a heavily reinforced central concrete core.

That provides a solid base upon which the detailing was added and there’s quite a bit of structural support but there’s a good reason for that. Building in Santiago comes with one challenge that’s more important than all others - earthquakes.

Chile sits in a seismic hotspot. Back in 1960, the nation faced the biggest earthquake ever recorded, coming in at a frightening magnitude of 9.5. That was a fair way up the coast from Santiago but the capital city faces its fair share of seismic events.

Granted, most are barely noticeable but every now and again, the city does face enormous ground shaking, like the 8.8 magnitude earthquake in 2010. Structures like Gran Torre have to be prepared. It’s why the tower’s fitted with a special outrigger system.

It works by connecting the exterior columns to the building’s core through a series of horizontal steel beams or trusses. It’s a bit like standing between two walls and sticking your arms out - you’ll feel a whole lot more stable than if you were just standing on two feet. At the base of the building, copper spring shock absorbers were fitted to the foundations to absorb seismic energy.

Above: Gran Torre features an variety of engineering solutions to make it seismically resilient (image for illustrative purposes).

What you might have realised is that this earthquake hit right in the middle of Gran Torre’s construction.

At this point, the tower was only two thirds complete, standing at 200 metres. You might think that would leave it less structurally stable but remarkably, Gran Torre came through the ultimate seismic test virtually unscathed. Its impressive outrigger system and base engineering absorbed any energy cast out by the earthquake, meaning work could continue on the tower later that same year but there’s another secret to Gran Torre’s success and it comes from the tower’s shape.

The glass wall facade tapers as it climbs towards the latticed, four cornered crown at the top and there are a couple of reasons for it. Firstly, the wind effects are lessened on a tower that slims as it rises. You can cut down on something called vortex shedding, where wind forces build up and swirl around a structure. A tapered design impacts the natural frequency and distribution of forces too. You can use the shape to direct the biggest forces towards the strongest parts of the tower.

However, despite its impressive engineering, Gran Torre has a lot of enemies.

Why so unpopular?

To offer some context, the second tallest building in the city, and actually anywhere in the country, is more than 100 metres shorter than Gran Torre.

While it’s a grand symbol of the continuing development of the city, it stands as a big glass reminder of wealth disparity. This enormous tower began construction in 2006 in Santiago’s most affluent area but come 2009, the nation found itself tangled in a recession following the global financial crisis.

Construction of Gran Torre ground to a halt for nearly a year, looming over the city’s residents as an incomplete reminder of Chile’s financial troubles, unemployment and personal debts.

But the problems go beyond what this represents financially.

To say Santiago’s population is around seven million people, more than three million visitors travel to this complex every month, and the city isn’t set up for it. This is more than just a massive office building = Gran Torre is the centre-piece of the Costanera Center which features four towers and a six floor mall. It’s right in the heart of the financial district, known to locals as ‘Sanhattan’.

Above: Gran Torre is in Santiago's financial district, known as 'Sanhattan'.

From the off, people complained the tower would cause nightmarish traffic because of a lack of improvements made to the nearby road network and while it came through protests, construction delays and a $600 million overspend to stand tall in Santiago, the traffic issues didn’t go away.

Come 2015, reports surfaced that Gran Torre was practically empty because the building’s owners hadn’t managed to sign any leases. They’d failed to get an occupancy permit from the government because the necessary road upgrades hadn’t been made around the tower.

Years of debate followed about whether upgrades would be publicly or privately funded and so Gran Torre stood, a $1 billion empty tower.

"When it comes to the shopping centre, yes, it’s a success, it’s one of the most profitable shopping centres in Chile. In terms of (Gran Torre's) legacy, it’s part of our skyline but still, the project has this issue with how to deal with the following stages and today is not fully open. But in terms of how we shape the city as a skyline, it’s a success", said Valencia.

It might be just one of more than 50 office towers occupying this ever developing space but there’s no denying it’s the biggest sign yet of a city straying from its architectural roots. What's impressive is that it managed to force its way above the skyline, overcoming all kinds of obstacles.

If Gran Torre can find a way, anyone can.

The people of Chile aren’t alone in wanting to protect their architectural heritage from buildings like this. Across South America, the same problem is shared - it’s one of the key reasons, amongst others, that the continent sits bottom of the pile when it comes to the world’s tallest buildings.

But Gran Torre feels like a key milestone for change. In the last 20 years, a number of skyscrapers have made the climb towards the skies as part of the South American skyscraper revolution and there are loads more on the way.

Gran Torre has set a precedent that you can build supertall in South America: a 300 metre symbol of the continent’s ever growing climb towards the skies.

This video and article contain paid promotion for Odoo.

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of The Nomad Photographer, CITY LAPSE, Professor Victor Correa / CC BY-SA 4.0, Luis Felipe Tapia Yanfka / CC BY-SA 2.0, Rodrigo Fernández / CC BY-SA 4.0, Mazilu / CC BY 2.0, Carlos yo / CC BY-SA 4.0, Canal22, Portal Abras / CC BY 2.0, Pablo Viojo / CC BY 2.0, B1mbo / CC BY-SA 2.0, JorgeGG / CC BY 2.0, JuanMarchant / CC BY-SA 4.0, Skellig2008 / CC BY 2.0, CBS, ABC News, Enrique Morris, Gerard Boberg, Gonzalo Baeza H / CC BY 2.0, Jimmy Baikovicius, Omnespsx / CC BY-SA 4.0, AFP News Agency, Juan Pablo Bravo / CC BY-NC 2.0, Deensel / CC BY 2.0, Diviena / CC BY-SA 4.0, Barto920203 / CC BY-SA 4.0, Dario Alperin, Jorge Barrios Riquelme, JorgeBarrios, Galdaniele, Universal Pictures, Sarariesco.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.