The Grenfell Tower Fire: London’s High-Rise Scandal

- Youtube Views 841,069 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills.

IT'S THE early hours of June 14, 2017, and a West London neighbourhood is about to suffer one of the most shocking human tragedies of recent times.

Not long after midnight, a resident of the 24-storey Grenfell Tower in North Kensington is suddenly awoken by a loud beeping sound. A fire has broken out in his kitchen on the fourth floor. He immediately calls the emergency services.

Within minutes, firefighters arrive to tackle the blaze, but it becomes immediately clear this is not going to be a routine job. Something is very wrong.

By the time they enter the flat, the fire has already spread outside onto the cladding that covers the structure, and it's climbing up the eastern face. Just half an hour after the call, flames have reached the roof and begin moving horizontally across the tower.

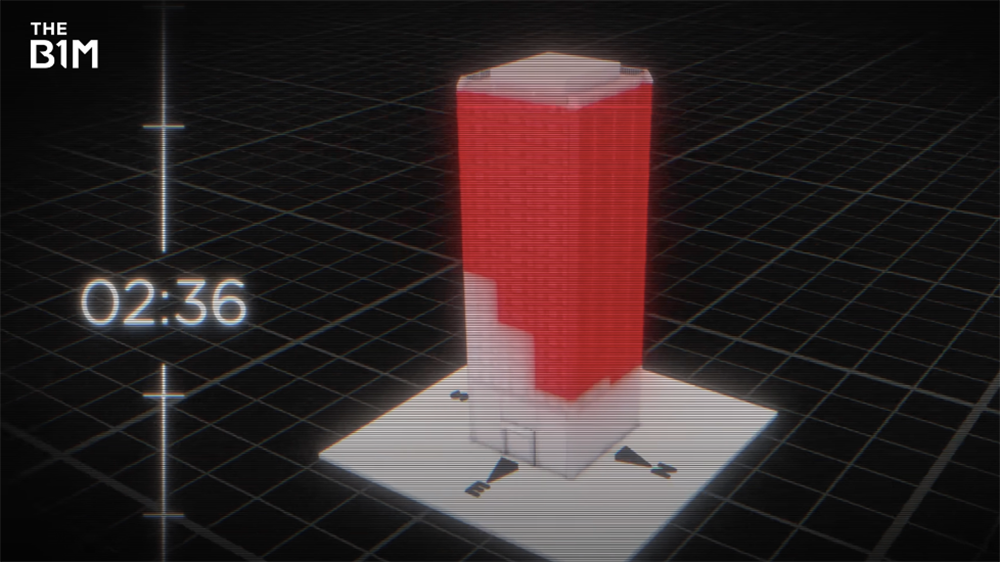

The Metropolitan Police declares a major incident after more calls from residents and, by 2am, only around half of the 297 occupants have escaped. At 2:35am, the fire has continued accelerating across the north and east sides, with flames now spreading to the south.

Those calling 999 are no longer advised to stay put, which is a standard policy when there's a fire in a high-rise building. They're now being told to leave. An hour later, the south and west elevations are ablaze and by 4:30am the entire building is engulfed. The fire climbed 19 storeys in a mere 12 minutes.

Above: A model of the tower, showing the spread of the fire. Model produced by The B1M from the Grenfell Tower Inquiry Report.

An entire day was spent bringing the fire fully under control, but by then the damage was already done. While 223 people managed to get out, 72 lives were lost. Almost half of them were disabled people and children.

The Grenfell Tower fire is one of the worst things to happen in the UK this century. Millions of Britons will never forget where we were when they heard the news.

But despite that, it's been easy to lose track of everything that's happened since. It feels like things have goten lost in this fog of bureaucracy, inquest and reports, and that there's been little in the way of progress.

Which is why The B1M wanted to find out what is happening, why it feels like not enough action has been taken, and how can it possibly be that people are going to bed tonight in buildings that could kill them.

The Causes

A week after the fire, some of the answers began to emerge. Police determined that the fire started with a faulty fridge freezer inside the flat where that first call was made.

The machine’s manufacturer and the resident himself have been cleared of any wrongdoing. But in the months and years that followed, those responsible for the building and its maintenance began to have their innocence firmly questioned, especially those involved in the decision to cover the tower in a particular type of cladding. That was a key element of the renovation that took place not long before the fire, partly to improve the appearance of a structure that had been built in the 1970s.

The project team selected a system of panels made from polyethylene plastic, surrounded by thin layers of aluminium – hence the name aluminium composite material (ACM). As well as helping to boost the building's visual appeal and thermal efficiency, it was chosen for another key reason: it was cheap.

Above: Fire crews fought to bring the blaze under control as dawn broke over London on 14 June 2017. Image licensed to The B1M from Alamy.

Indeed a lot of the decision making here was to do with money. Believe it or not, Grenfell Tower actually sits in the most expensive neighbourhood in all of London. It's called the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), where the average house price is over £1.1M.

An investigation discovered that in the years before the Grenfell disaster, the council made £129M from selling properties. The refurbishment of Grenfell cost around £9M, but in the same period, they spent more than £60M on new property.

When it came to refitting that building at the other end of the borough, where things weren't quite as luxurious, they went for the budget option. Rydon, the main contractor for the refurbishment, found that picking ACM over other alternatives like zinc cladding could save around half a million pounds.

Even when it emerged the figure had been overestimated by subcontractor Harley Facades, Rydon organised the finances so the error wouldn't hurt their profits. Or, in the words of the firm's commercial manager, Zak Maynard, in an email to his boss, it would leave them “quids in.”

It was that cost-cutting measure that would have devastating consequences. They were opting for a material that was highly flammable and shockingly that wasn't even a secret.

Since as far back as 2005, Arconic, the firm that makes the cladding, had seen one of its products fail fire safety tests in France on multiple occasions.

One version of the manufacturer's cladding is known as a cassette system, where the panels are folded so the fixings can't be seen.

Above: Grenfell Tower after the renovation. Image courtesy of Grenfell Tower Inquiry.

However, experiments have shown the cassette performs far worse when exposed to fire than the alternative riveted methods, and it was the cassette system that was chosen for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower.

It was supplied by a firm called AAP, which is a subsidiary of Arconic. However, during the inquiry an email came to light, sent by one of Arconic’s bosses to his co-workers.

Written back in 2010, it showed that not only were Arconic aware of the test data, they were asking for it to be kept “very confidential.” Still, sales continued for years afterwards.

Another test was carried out in the UK even earlier by the Building Research Establishment or BRE. The catastrophic results were shared with the government but not the building industry.

It wasn't just this one firm supplying what turned out to be dangerous products for use on the building. The refit also featured insulation from Celotex and Kingspan, although the latter only provided around 5% of it.

Still, the important thing is, all of these products were combustible and were sold using test data that had been deliberately manipulated.

The Stay-Put Policy

Now, the cladding has been identified as the primary cause of the fire's spread, but that wasn't the only factor that made this disaster so deadly.

The first major report into what happened, published back in 2019, partly took aim at the London Fire Brigade. Its decision to revoke the stay put policy nearly two hours after the fire had started was seen as far too late.

We should briefly explain why residents living in a building where there's a fire in another part of it are told to stay put in the first place. They're asked to remain in their homes, close all doors and windows, and wait until either the fire is put out or they're rescued.

It's because most high rises are designed so a fire can be contained and cannot spread internally. They might also have narrow single staircases like at Grenfell, making mass evacuation difficult.

Because it was obvious that the fire was spreading fast on the outside rather than on the inside, critics say people should have been told to get out much sooner.

To make matters worse, there were no sprinkler systems in place and the fire doors only offered half the amount of protection they were supposed to.

“We'd been instructed by our landlord with a stay put policy. So my first thought was, I'm just going to remain here. I'm going to stay in the flat and call the fire brigade,” explained Edward Daffarn, a former resident at Grenfell, who survived the fire.

“And then literally as I was thinking that, my phone rang. It was a neighbour of mine who had already got out of the building. And he just shouted down the phone at me. He just said: ‘Get out. Get out now.’ There was something so powerful in his voice that I just, there and then, made my decision I was going to go.”

Above: Grenfell Tower resident Edward Daffarn chose to leave the burning building.

The building's landlord was the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, or TMO, which has been accused of a 'culture of concealment' over a previous fire in 2015. It was found to have hidden key information about fire safety from its own board and treated the matter as an inconvenience.

The Report

If you think that's where the controversy ends, sadly it represents just the tip of the iceberg. At the conclusion of the inquiry, a huge report was published that finally offered some closure on what led to this catastrophe. It ran to 1,700 pages and it didn't hold back in its condemnation of various organisations who all had some involvement in what transpired on that dreadful night.

“Those who lived in the tower were badly failed over a number of years and in a number different ways by those who were responsible for ensuring the safety of the building and its occupants,” said the Chair of the Inquiry, Sir Martin Moore-Bick.

That list of those responsible that he is referring to was incredibly extensive. It included the UK Government, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the Tenant Management Organisation.

Those involved in supplying and manufacturing the cladding material were also heavily criticised, including firms involved in the refurb, the contractors and the architect Studio E.

They were singled out for taking a casual approach to contractual relations, specifically for not checking the materials met regulations.

These firms were all accused of systematic dishonesty. According to the report, Celotex was said to have “misled its customers and the wider market,” Kingspan “cynically exploited the industry's lack of detailed knowledge” and Arconic “deliberately concealed” the “true extent” of its product's dangers.

Then you have the people who certified the use of flammable materials, consultants, the London Fire Brigade… it just goes on and on.

Moore-Bick added: “Not all of them bear the same degree of responsibility for the eventual disaster, but as our reports show, all contributed to it in one way or another, in most cases through incompetence, but in some cases through dishonesty and greed.

"Decades of Failure"

We've already covered what the cladding manufacturers and other firms behind the refurb did wrong. But as to what the UK government did wrong, in the eyes of the report's authors, it was more about what it didn't do.

From as far back as the 1990s, governments run by both of the UK's two main political parties oversaw decades of failure. 26 years before Grenfell, another tower block, this time in Liverpool, caught fire with flames spreading up the combustible cladding.

Thankfully, nobody was killed in that incident, but it was one of many opportunities for the government to identify the risks of those kind of materials and to take action to address them, according to the report.

Above: The Grenfell Tower Inquiry report was published in 2024.

And that wasn't the only warning sign that got ignored prior to the Grenfell disaster. Along with another resident, Daffarn unearthed some serious problems with the building, but wasn't listened to.

“[There were] fire extinguishers with ‘condemned’ written on their sides, the lifts never worked, they were legitimate concerns,” he recalled.

“We wrote a blog in November 2016 saying that it will take a serious fire and the loss of life in a property managed by our landlord before anything is done about the way that our buildings are being looked after, and then, terrifyingly, all those predictions were found to be true.”

The Progress

It's been almost a year since the inquiry published its final report, and eight long years since the fire itself. But what's actually happened in that time? Surely you'd think there'd be some kind of massive overhaul to prevent something like this from ever happening again. Yes, there have been some big developments, but we're still a very long way from getting this situation fully resolved.

Firstly, ACM cladding is now banned on all new high-rise residential building projects in the UK. That's been in effect since late 2018.

Then came the Building Safety Act 2022, which gave residents and homeowners more rights, powers and protections. For example, leaseholders living in high-rises buildings no longer have to pay to have unsafe cladding removed.

Fresh regulations were introduced to give more clarity on how these structures should be constructed and maintained safely, and three new bodies were created to provide oversight of the changes.

More recently, in February 2025, the UK government set out what it called tough new reforms to fix the worst issues exposed by the tragedy.

They include a new construction regulator to make sure those responsible for building safety are held to account. Crucially, there will now be tougher oversight of testing, certification, manufacturing and use of products like cladding. And if residents have concerns about where they live, those reforms ensure stronger legal rights to challenge landlords on safety.

That same month, the UK government accepted the findings of the inquiry's report, pledging to take action on all 58 of the recommendations contained within it.

49 of those recommendations were accepted in full. They cover everything from fire safety and regulations to evacuation plans. But nine of them were only accepted in principle, leaving some room for doubt on whether they'll ever be fully implemented.

"One of the things we're going to be doing as a committee is going through the recommendations that the government have now accepted in full, which I think is the right first step,” Florence Eshalomi MP told The B1M. She chairs a committee that scrutinises the work of the department responsible for housing and the response to Grenfell.

“We had in our evidence sessions some of the survivors from Grenfell, some of the next of kin family members, and on the back of our mini-enquiry we're going to write a formal letter to the government with some our initial recommendations.”

Above: The B1M's Fred Mills interviewing Florence Eshalomi MP in Westminster.

You would assume that since that cladding ban came in more than six years ago that there would no longer be any buildings that don't meet the requirements. But shockingly, that's not even close to being true.

The government's own data from February 2025 revealed that some 2,000 social housing buildings haven't been remediated yet. They've still got dangerous cladding on them that hasn't been replaced with something safer. Even more unbelievably, almost 500 of those buildings have no form of remediation plan in place at all.

And it's not just social housing tenants who've been living in buildings with major fire safety issues. Thousands of leaseholders — that's people who own a property but not the land it sits on — have also found themselves in homes with similar defects to Grenfell Tower.

“It was in the first few weeks after Grenfell where there were a lot of security fire safety checks of buildings to make sure the cladding was safe. We were told initially by a property management company and the fire service that things looked OK,” said Giles Grover, co-lead of End Our Cladding Scandal, a campaign group of leaseholders who've been fighting to ensure all buildings with unsafe materials are fixed.

“Literally two or three weeks later we got some results saying it's the same ACM category three that's on Grenfell's. So from then on our lives have changed completely.”

Grover, who lives in Manchester, became frustrated with the lack of action from developers and local authorities on who should pay for the work. It got to a point where they felt they had to take matters into their own hands.

“We just end up going around in circles for at least a year. So I became the property manager of my building — probably one of the worst ideas I've ever had. But the managing agent wasn't doing the best job, not really covering themselves in glory, should we say,” he explained.

“So I took it on. I thought, ‘right, I'll be able to sort this. I can fix my building.’ Yeah, that was 2019. So six and a half years ago, and I've been a campaigner since then. That's been pretty much what I do full time really, day in, day out.”

Back down in London, another resident, Robert Zampetti, has had to take the owner of his building to court because they still haven't rectified what he calls a death trap. It’s fitted with expanded polystyrene, or EPS, for insulation and cosmetic purposes.

“EPS is highly flammable. There are situations, I am told, where it can be used, but then you have to think very carefully about what's in front and in back of it. And that just not, hasn't been done here,” Zampetti said.

Although Zampetti's building was identified as needing remediation, disagreements between the developer and the freeholder which owns the building means that work still hasn't started. He and his fellow leaseholders got so fed up they applied for what's called a first tier tribunal to get the process unstuck.

Unidentified Buildings

We should clarify that not all those buildings we highlighted before have or did have ACM cladding on them. When it comes to that type specifically, more than 80% of high-rises have been fully remediated.

But that still leaves dozens of buildings where the work hasn't finished or hasn't even started yet. According to a National Audit Office report that was published in November 2024, up to 60% of the buildings with dangerous clad on them haven't even been identified yet.

A deadline has now been set for all work to be completed on high rises over 18 metres, but that deadline is in 2029 and even that is only for a small proportion of the buildings out there that may have cladding in need of replacement.

“What happens to everyone else? No one knows when their homes, their building will be made safe. That's the issue,” said Grover. “Having a high-level target date? Great, But knowing when my home will be safe, when I can move on with my life, that's what people want to know.”

Above: Unsafe cladding remains on thousands of buildings in the UK.

It's going to be expensive, too. Fixing unsafe cladding on all residential buildings over 11 metres tall has been estimated at more than £16BN. Just over £9BN of that would need to come from central government with the rest coming from developers, private owners and social housing providers. Taxpayer funding has been capped at £5.1BN.

The Wait for Justice

So now we know the sheer magnitude of the failures that led to the Grenfell Tower disaster, and that multiple parties had a role to play in it, what are the consequences?

Well, criminal proceedings are a very real prospect, including prosecution on things like corporate manslaughter, gross negligence manslaughter and misconduct in public office.

The Met Police has been looking into these possible offences since before the final report was published. But we're not going to know the outcome of that process until at least the end of 2026.

In the meantime, seven of the firms who were involved in the tower's refurbishment may face punishment of a different kind. The government's announced debarment investigations, which could see them banned from working on future public contracts.

Even so, the three firms who are involved in producing the cladding and insulation products in the Tower have all come out to defend themselves.

Arconic’s response to the final reports maintains their product was safe to use as a building material and rejected any claim that AAP sold an unsafe product.

It also stressed that it did not conceal information from or mislead any certification body, customer or the public, despite this seeming to contradict the results of the inquiry.

In its own statement, Celotex took a different approach, revealing how it's been making improvements since Grenfell. These include reviewing and improving process controls, quality management and the approach to marketing to meet industry best practise.

And Kingspan has acknowledged the wholly unacceptable historical failings that occurred in its UK insulation business and that it has emphatically addressed these issues. But it also pointed out the principal reason for the fire's spread was the ACM cladding, which it didn't make.

“Some, at least, of the core participants would indulge in what I termed a merry-go-round of buck-passing,” said the inquiry’s lead counsel Richard Millet KC. “I had hoped that my task … would be made easier by candid admission of blame.”

But that wouldn't happen. Millet showed what he called a spider's web of blame on the final day of proceedings, demonstrating how companies tried to place others at fault for the disaster.

Above: Today Grenfell Tower is wrapped in protective sheeting. Works to dismantle it are due to begin in the months ahead. Image by The B1M.

For the families, survivors, and the many, many people who were so deeply affected by what happened here in 2017, there's been a long and agonising wait for answers and for justice.

One of the questions has been, what's going happen to the future of the tower itself? Is it gonna stay standing or is it going to be demolished? And we recently got some clarity on that.

The government confirmed in February 2025 that it will be carefully taken down to the ground, from top to bottom, in a process that's going to take about two years. Nothing is going to happen until after the eight-year anniversary of the disaster this June.

But it's a decision that not everyone agrees with, and some people with connections to those who died believe they weren't properly consulted.

Many feel the tower should remain standing as a lasting reminder to the tragedy, even just in some form, or that it should at least remain in position until there have been prosecutions.

But that's going to take a while. And according to the government, engineers report the building is significantly damaged. Although it's been kept up until now, that's largely because of those special protective measures, and it's expected that the tower's condition is going to worsen over time.

Never Again

This has been one of the hardest and most challenging stories The B1M has ever told. There's so much detail, so much history, so much nuance, so many personal stories, hours and hours of inquiry footage and that 1,700 page report.

How could this have happened in London? And why has so little has been done about it? Yes, there have been some steps, but we're still in a position where this cladding remains on buildings, putting people's lives at risk.

Every time we go inside a building, we put our faith in the people who designed, built and maintain it. They have a responsibility to keep us safe. The horror of Grenfell Tower shows us what happens when that responsibility gets pushed aside by greed.

This video is dedicated to the victims and survivors of the Grenfell Tower fire.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Grenfell Tower Inquiry, ABC News, BBC News / Newsnight, Bloomberg, CBC News, ChiralJon / CC BY 2.0, David Pickup, Declan Conor, 5 News, ITV News, Natalie Oxford / CC BY 4.0, NBC News, Nick Hawkes, On Demand News, Reuters, Sky News, Tamas Babai and The Independent.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.