What is China Hiding Under Its New London Embassy?

- Youtube Views 1,528,566 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Brilliant.

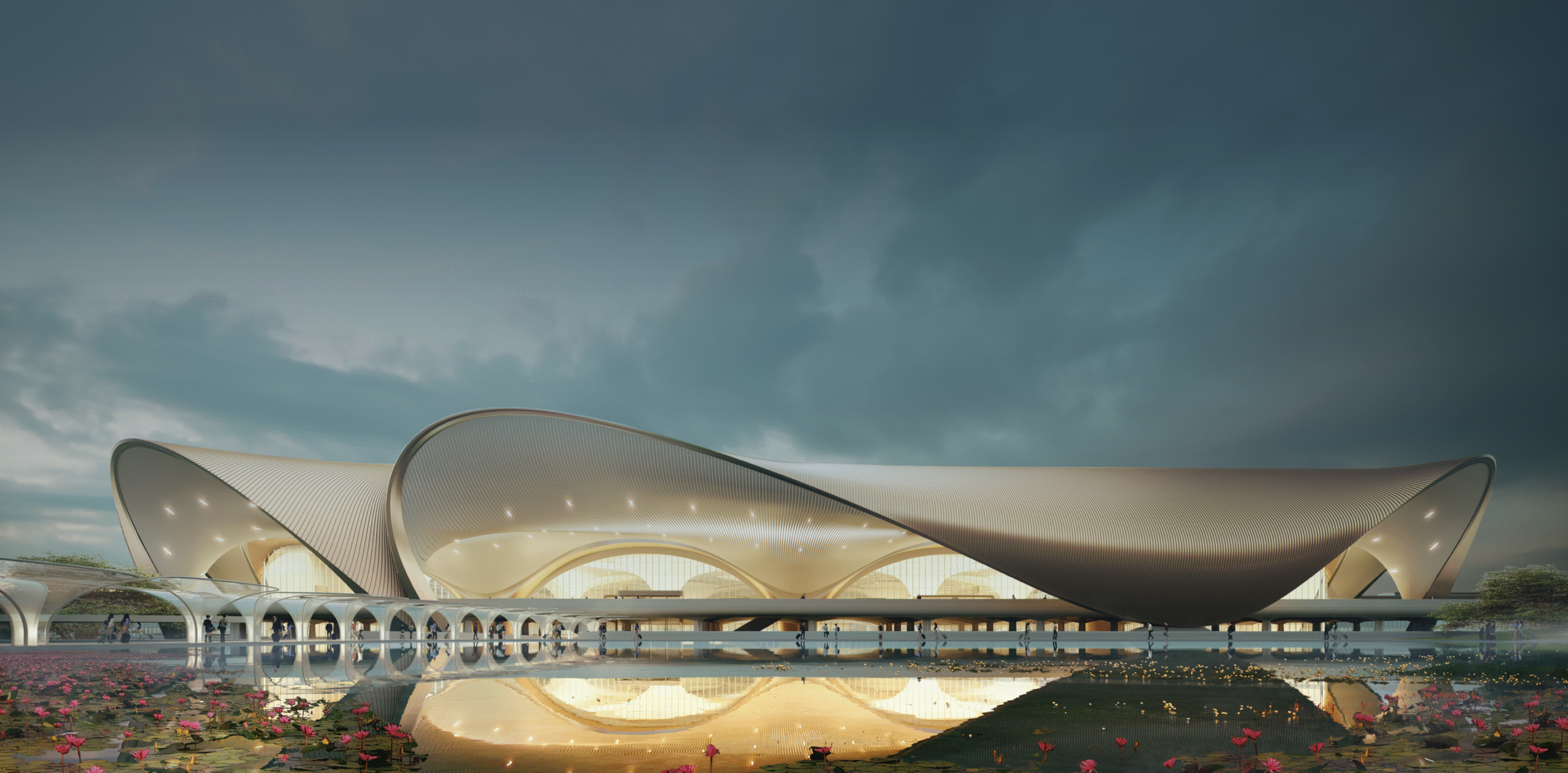

LONDON’S ROYAL MINT COURT once sat at the heart of the British establishment, but, depending on who you listen to, it could soon become a grave threat to national security. That’s because a planning application is underway to convert this storied site into the new Embassy of the People's Republic of China.

Warnings are being sounded by everyone from local residents to heads of spy agencies: secret dungeons, hidden tunnels, wire tap facilities. According to its critics this has the potential to become the centre of the biggest espionage operations in Europe.

But, it could also be what its owners say it is: the home of a fraught but budding relationship between two nations with a lot of history.

If it gets built, Royal Mint Court wouldn’t just be the biggest embassy in London, but in the whole of Europe. Although that’s a big if, because since plans were first drawn up in 2018, this has turned into the most controversial development in Britain.

Above: The Johnson Smirke Building, the centrepiece of Royal Mint Court.

Embassies occupy an unusual place in our built environment. On a functional level they are offices, full of people doing the kind of boring things we all do in offices. But beyond that, it’s a statement, an image of a country projected through Portland stone and cream stucco.

They’re governed by a very unusual set of laws, chief among them being the golden rule of international diplomacy which means the building and the staff inside it are off limits to anyone except the country it represents. Over the years, this has become very useful for conducting more than just diplomatic business. Former British Military Intelligence officer Philip Ingram told us more:

“The role of an Embassy is to represent the government of the country that that embassy represents to the government of the countries that the embassy is based in… but then it also acts as a cover for secret intelligence”

London’s 49-51 Portland Place is currently where the People’s Republic of China currently calls home in the United Kingdom. In a sign of how far back relations between the two countries go, this is actually the first embassy China established anywhere in the world.

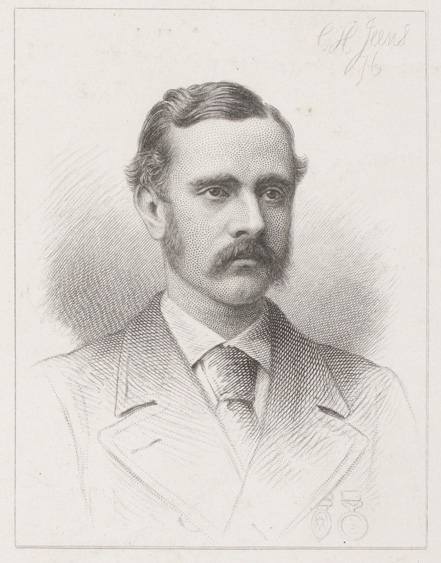

It was set up by the Qing dynasty in 1876 in the wake of the Margary Affair, in which Colonial explorer Augustus Margary was killed while establishing trade routes in western China. British officials used this as a pretext to force China to sign an unequal treaty which demanded, among a lot of other things, that an envoy from the Qing dynasty be sent to personally apologise to Queen Victoria.

Above: Augustus Margary.

The house the legation stayed in became its permanent diplomatic mission which has remained there ever since. The current building however is an enlarged reconstruction. As the number of staff grew, the original was knocked down and rebuilt in 1985 with a reinforced concrete frame faced with brick. The design of the facade was kept but the rear was extended and mansard roofs were added on top.

It may look big, but it’s not quite big enough. Much of China’s consular and visa work is spread across offices around London. So, in 2018, the People’s Republic snapped up a semi-abandonned former industrial site: Royal Mint Court.

The site contains several buildings spread across five and a half acres of prime London real estate. As the name suggests, it used to be the home of the Royal Mint, where all of Britain’s money was printed. As recently as 1970, every pound and penny in the country came out of this compound.

As august as the site may be, the complex itself wasn’t exactly “move in ready”. Various tenants passed through the mint since it closed in 1980, but it sat empty for years before being bought by the Chinese government.

To transform it from a fixer upper into a world class embassy, the Chinese government hired David Chipperfield Architects, one of Britain’s most celebrated studios.

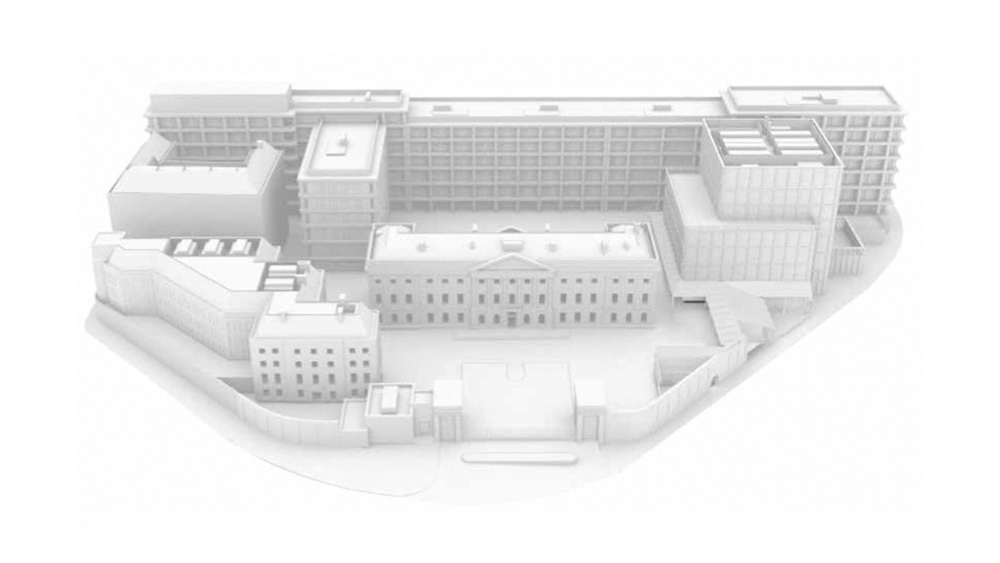

Above: An overview of David Chipperfield Architects plans.

The plan they came up with would see the iconic Johnson Smirke Building remain the centrepiece of the complex, with the ground floor used for ceremonial engagements. The entire building would be refurbished and upgraded with a modern MEP system.

Another historic building on the site, The Seaman’s Register, would be significantly remodelled to transform it into a single, coherent building. Its Georgian entrance would be kept and restored, and the ground floor fitted out for diplomatic reception areas. The 1980s exterior on the west side would be replaced with a vertical brick facade to unify the building’s aesthetic.

The biggest challenge was presented by the Dexter and Murray House, two office blocks added in the 1980s. The brief was to keep as much of the original buildings as possible, but here Chipperfield came up against a whole raft of issues.

Enclosed almost entirely by old glass panels, insulation is a chronic problem. Making this worse is the expressive steelwork that comes out of the frame of the building. This may have been the height of fashion 40 years ago, but everywhere it joins with the glazed facade it creates a thermal bridge.

To solve this, both buildings were extensively redesigned. The larger Dexer House, at the rear, is to become accommodation for embassy staff. The inefficient cladding and 80s steelwork is out and a restrained, minimalist facade is in. This new look also gives a more demure framing for the Johnson Smirke building.

In keeping with the brief to re-use as much as possible, the overall structure including the internal steel frame and floorplates were to be kept, albeit with a few tweaks. The original office building featured deep floorplates which are unsuitable for accommodation.

To solve this, the line of the facade would be taken back into the building, reducing the interior size and providing each apartment with a balcony. To reduce heat loss, the new facade would be a mix of materials and the floorslab edge given more insulation.

Above: The west elevation of Embassy House.

Murray House would be redeveloped as another showpiece building, The Cultural Exchange. The lower ground floor will be used for Visa services with offices and a space for cultural events above.

Just like with Embassy House, much of the structure of the original building is being kept, but in a nod to the UK and China’s shared history of ceramics, its finish is to be clad in celadon glazing. A grey-green colour traditionally used in Chinese pottery to represent the sky after rain – so, perfect for London.

Back in 2018 when planning began, spirits were high. Ambassador Liu Xiaoming declared that the new premises were the “golden fruit of a China-UK "’Golden Era’” and an embodiment of “China's dream for a harmonious world”. In June 2021 the Chinese Diplomatic Mission submitted its plans to the local authority. And almost immediately, their hopes came crashing down to earth.

In the intervening years, relations between China and the UK had deteriorated and as a result, the fruit also began to sour. Heritage groups objected to the symbolism of such an historic site being transformed into a foreign embassy, while local residents living next door to the site said their concerns had been ignored.

At a local council meeting, a motion was tabled to rename neighbouring streets in protest of China’s human rights record.

But the loudest objections came from the shadows. Concerns from the intelligence community circled on the threat of espionage. It turned out the prime location of the embassy would give it access to much more than just prestige.

Royal Mint Court sits between the City of London and here is Canary Wharf, which together they make up the second largest financial hub in the world. According to Ingram,

“It's got a physical view of a lot of the buildings in the City of London. And where you've got a view, you can have antennae that can intercept wireless signals”.

Above: The City of London.

But what’s above the embassy is not nearly as concerning as what’s below it. The masterplan of the Embassy’s basement submitted to the local planning authorities shows service cores, vehicle entrances and a parking layout. But it doesn’t show much else.

With secure buildings it’s normal to redact some information on publicly available documents, but the sheer size of the restricted basement areas caused panic among security analysts.

Such worries aren’t unprecedented. In 2020 the Irish government rejected a proposed extension to the Russian embassy in Dublin, which contained plans for a vast basement. The facility would have included 20 storage areas, 13 toilets, and four unmarked rooms.

But there was another very specific reason officials had to be concerned about the threat this basement posed. Running through the area are communications cables linking London’s two financial hubs.

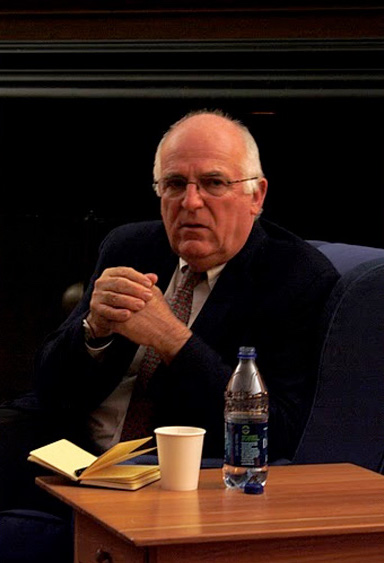

Although the exact location of these cables is secret, the risk to them was enough to cause the former head of MI6, Sir Richard Dearlove, to speak out against the plan.

Above: Sir Richard Dearlove.

In an interview with the i newspaper, he claimed “If there are cables under the site… the Chinese with impunity… can link into them [and] listen to everything or collect anything and everything going down those communication chains.”

Shortly after the planning application was made, the head of Britain’s domestic spy agency, MI5 and the director of the FBI gave a speech warning of Beijing’s “industrial” levels of espionage.

In a statement, the Chinese embassy condemned these remarks calling them “fabrications” and urged the UK to “do more that is conducive to mutually beneficial cooperation between China and the UK”

But in December 2022 when the local planning committee convened to pass judgement on the proposal, its fate was already sealed. Councilors voted unanimously to reject permission for the new embassy.

No appeal was launched against the verdict and with that, the plan was dead in the water. But 18 months later, the UK held a general election in which Labour was returned to power. Just a few days later, another application for planning permission was submitted for an embassy at Royal Mint Gardens, using an almost identical set of documents.

But why would the local planning committee have a change of heart now? Well, the election had dealt the Chinese government a rather favourable hand. To build anything in the UK, whether it's a bungalow or a skyscraper, the project owner first needs to apply for planning permission through their local council – in this case, Tower Hamlets.

99 percent of the time, their decision is final, but, in special cases, a government minister, the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, has the ability to “call in” an application and make the final decision themselves. And in November 2024, that’s exactly what happened.

Post-election, a flurry of diplomatic activity between the two governments ensued, in an effort to enter yet another new era of relations.

Above: UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves meeting Chinese Minister of Finance, Lan Fo'an in 2025.

“The Chancellor of the Exchequer wants to exploit opportunities with the second largest economy in the world, which is China. And therefore, to try and get something back you have to give something.”

That something is the embassy. But as the new government flashed Beijing an ankle, the backlash at home was huge. Activists, the media and politicians of all affiliations mobilised to protest against any change of heart.

With the final decision out of their hands, the Tower Hamlets planning committee rejected the re-submitted proposal in a symbolic vote.

The opposition even spread beyond Britain’s borders. In June this year the White House warned the new embassy would pose a national security risk and could endanger intelligence sharing between the two countries.

A final decision on whether or not permission will be granted is due in September. Which way it will go is anybody's guess. But regardless, this whole episode highlights a dramatic reversal of fortunes for China and the UK.

China is no longer the humiliated party arriving on bended knee, while the UK is tossing up whether it can afford to trade its security for its economy. Behind closed doors, the story of this embassy is anything but diplomatic.

To try everything Brilliant has to offer for free, visit https://brilliant.org/TheB1M/ You’ll also get 20% off an annual premium subscription.

Additional footage and images courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects, BBC News, Sky News, Royal Mint Museum, RTÉ News.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.