Is Colorado’s Massive Dam Expansion in Trouble?

- Youtube Views 515,931 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Sky Systemz.

TUCKED away in the mountains of Colorado is one of America's most unusual construction projects.

The Gross Reservoir has been supplying the city of Denver with much of its water for more than half a century.

But not enough it would seem. With more demand on the system than ever before and natural disasters becoming increasingly likely, this man-made lake now needs to be a lot bigger.

It's reasonable to assume a reservoir can only be as big as the dam that created it. Which is why teams here are having to pull off a rare and difficult task first. They're expanding the dam itself by building a new one on top of it.

And yet, with the finish line now in sight, there's a serious problem that won't go away — one that's already seen this gigantic scheme stopped in its tracks.

Waterworld

Just outside Denver, Colorado is where the Rocky Mountains begin and a great deal of water can be found. There are lakes, reservoirs, the Colorado River, and its tributaries all within reach.

It's a good place to be if you like the quiet life. Except that is for one particular site in Boulder County, which has become a hive of activity in recent years.

Above: The Gross Reservoir is situated northwest of Denver. Image courtesy of Mitch Tobin + The Water Desk + Lighthawk.

Back in the 1950s, a large gravity dam was built here to serve the Denver metropolitan area. Due to its rising population, the city needed a new water source to keep up with increased demand and resources, and so the Gross Reservoir was born.

But reservoirs don't just fill up on their own, of course. A massive wall of concrete, the Gross Dam, had to be built first.

It would capture water coming in mainly from the Fraser River, which joins onto the mighty Colorado River via the Moffat Tunnel.

Okay, but before we move on, why is it called the Gross Reservoir? Well, it's not because it's disgusting, or due to its size, which is pretty substantial. It's actually named after Dwight D. Gross, who was the former chief engineer of Denver Water.

That's the utility company that owns and operates both the reservoir and the dam. Sorry to ruin the fun, but at least you now know.

Expanding capacity

When full, the reservoir is capable of holding 42,000 acre feet — around 52 million cubic metres — of water. And for decades, that was absolutely fine.

Until 2020, when Denver Water got permission to expand the reservoir by making the dam even bigger by over a hundred feet.

That would see capacity increase almost threefold to 119,000 acre feet, or nearly 150 million cubic metres. Enough to supply 72,000 homes with water every year.

Above: The original Gross Dam under construction in the '50s. Image courtesy of Carnegie Library for Local History, Boulder.

"What that led to is a ginormous project to build a 131-foot dam raise on top of a 340-foot-tall dam," said Jeff Martin, who leads the team at Denver Water, with responsibility for the entire programme from concept right through to completion.

"Building a 471-foot concrete dam in 2025 is a challenging endeavour on a number of fronts. That is big under any standards throughout the world. And it's extremely rare what we're tackling really just to provide a secure water future to the Denver area."

Why does it need securing? Well because over the years, Denver and neighbouring Boulder County have become increasingly vulnerable to water-related disasters.

Climate conundrum

There's more than just snowy mountains in Colorado. It can get very hot, dry, and also pretty wet here too. 2002 saw an unusually serious drought, along with the Hayman Fire, which destroyed well over 100 homes.

So, having more water available to deal with such problems, if and when they occur, starts to make sense.

Population growth doesn't show any signs of stopping either. In 2020, Denver Water announced that daily users had risen to 1.5 million people — 100,000 higher than just four years before.

There's a pretty big imbalance with where it stores its water as well. 90% of it is held in reservoirs to the south of Denver, with the other 10% to the north where Gross Dam is.

But despite how it might sound, expanding this rather imposing piece of infrastructure is actually not a new idea. In fact, it was kind of the plan right from the beginning.

You see, the dam was constructed with the intention of being raised at least once, should that become necessary in the future, which it clearly has.

Above: Denver Water's user base has been growing exponentially.

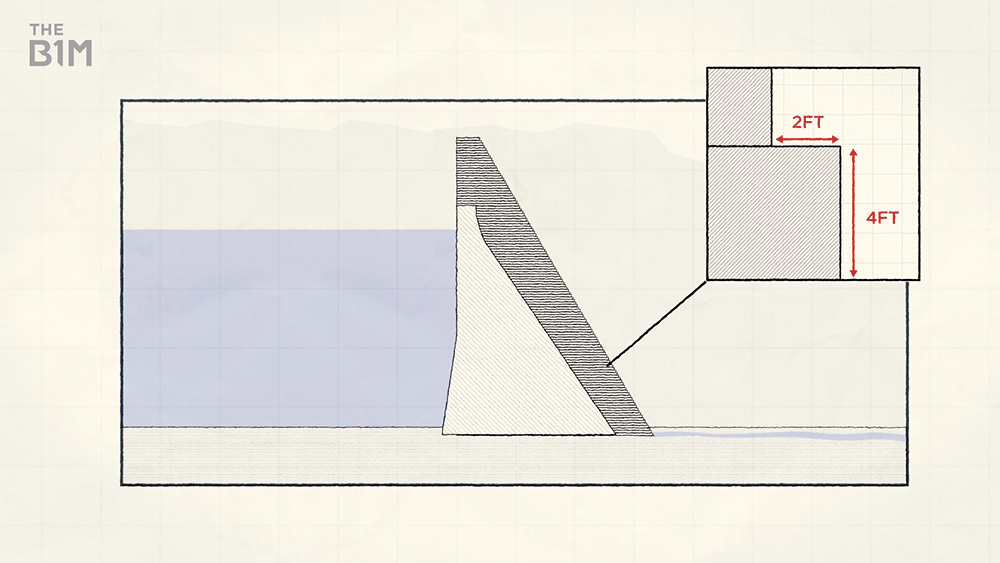

The idea is obviously to add more concrete to the existing dam, but not just on top. They're having to build up the south facing or dry side as well to help maintain stability.

To achieve this, 118 concrete steps are being constructed from the ground right up the top of the new dam.

Then the crest — or tip — goes on, followed by a control building, electronics, railing, and bridge across the spillway.

Construction began in 2022, and by June 2025, workers had reached the height of the original dam, more than 7,000 feet above sea level.

As for the method used to create these steps, Denver Water has chosen a different approach to the original dam's builders.

(Un)conventional concrete

"There's two ways to make a concrete dam. One is with what we call conventional concrete," explained Martin. "That's how the original dam was built, and it's basically built in 50-foot blocks all the way up. Just like Hoover [Dam] was, and some of the other iconic concrete dams throughout the world were done.

"In the 1980s, a new method came into existence through innovation. It's called roller compacted concrete."

Above: Each step on the new dam is four feet high and set back two feet from the one underneath.

What does it involve? First, the concrete is brought in by dump truck, which, well, dumps the material on top of the surface.

Next, it's spread by a bulldozer before being rolled and compressed by a smooth drum compactor. The concrete's made on site — a mixture of rocks, cement, fly ash, and water.

While other dams have been raised before, this is the largest one in the world to be done using RCC.

"We had over 600,000 yards of conventional concrete, and we're going to overlay that with over 700,000 yards of new roller compacted concrete," Martin added.

"The mix design itself, the temperatures that it had to maintain during placement, and how it was placed against the old dam were all extremely critical details on making sure that this dam behaves as one dam going forward."

This choice of material offers lower curing temperatures, meaning it doesn't take as long to set as regular concrete. Embodied carbon is reduced as well, and it's less likely to crack.

Stumbling block

Everything appears to be going to plan so far, then. However, In April 2025, all construction on the project was put on hold following a court injunction.

A US district judge ruled in favour of environmental groups who've been campaigning against this expansion for years. They include the Waterkeeper Alliance, Sierra Club, and Save the Colorado.

They believe the new larger reservoir will have a negative effect on the wider Colorado River water system as well as nearby residents.

Above: Gary Wockner of Save The Colorado.

"It would drain more water out of the Colorado River. It's in crisis mode. All the states in the southwest United States are trying to decide how to use less Colorado River water, and this one would use more," commented Save The Colorado director Gary Wockner.

"The second reason is that they would it would be and it has been the biggest construction project in Boulder County history. There's about a thousand houses up and around the area. It's been an extraordinary nightmare for those people living through this 24-7 construction process."

Adding credence to these claims, it emerged the US Army Corps of Engineers, which supplied the permits, didn't factor in the full environmental impact when it approved the project.

According to the judge, viable alternatives to this expansion were not properly addressed, which led to a somewhat unlikely win for Gary and his team in court when you consider who they were up against.

Back in action

But it was only a temporary pause. Just a month later, the judge did a U-turn, after claims from Denver Water that leaving the dam unfinished could lead to serious consequences. Like flooding.

That meant construction could continue, but there was still one pretty big issue remaining. Although they got the green light to carry out the works, permission was not given to actually fill the expanded reservoir — at least not yet.

New permits would need to be signed first, but because the Army Corps of Engineers made extensive and serious errors, it's unlikely to be straightforward. So there's a chance that all of this could be for nothing.

Above: The process of filling the enlarged reservoir is expected to take around five years, but we still don't know when, or even if that can happen.

Okay, but let's rewind a bit and dig a little deeper into what exactly it is that campaigners are unhappy about.

If this dam's already been here for about 70 years, then what's wrong with just making it a bit bigger? Surely that's better than building an entirely new dam and reservoir somewhere else?

Mitigation measures

This is one of the mitigation measures that Denver Water has put in place to limit what could otherwise be a much larger impact on the local environment.

By storing extra water in the reservoir, they can also direct more of it into the adjacent creek, improving fish habitats.

They're also introducing new wetlands and preserving other areas to offset some of the deforestation that has to happen on a project like this.

Around 200,000 trees are being removed, which is sort of inevitable when so much land is being inundated, and water quality has to be maintained.

"There's only one way to tackle a project like this, and that's with a culture of environmental stewardship and making sure that we're fully analysing the impacts from the project," said Martin.

"We've done a lot of different mitigation to make sure that in the end that this is a net environmental benefit to the state of Colorado."

Above: Denver Water's Jeff Martin.

That might be so, but Gary isn't convinced. He believes the impact of these dams is just too great, not just on the local area, but on the whole Colorado River basin.

"Dams kill rivers. That's what dams do. They block a river — if it's a hydropower dam they block a river and completely change the flow of the water in the river," said Wockner.

"The climate scientists claim drought and climate change have lowered the flow in the whole entire Colorado River around 20% from its original flow. And so the river's already been devastated. This will make it worse, and that's why we're opposing it."

The price tag

Then there's the cost of all this. When the project gained approval in 2021, the price was set at $531 million, and that remains the most widely reported figure.

But when you factor in the unexpected legal costs and the new permits that now need to be done, there's a good chance that number's going to rise.

As for where that money comes from, unlike a lot of American infrastructure projects, it won't be tax dollars.

Denver Water is funded entirely by ratepayers, fees for connecting new customers, and the sale of renewable energy. Gross Dam has been home to its own hydro plant since 2007.

Despite the problems the companies faced, their reservoir's latest upgrade isn't too far from the end. 2026 is when they plan to top out on the dam and finish the spillway and supporting buildings. A year later, it'll be time to start filling the reservoir, assuming they've been cleared to do so.

Above: Construction is nearing completion. Image courtesy of Denver Water.

Like so many other projects that have had some major issues, the Gross Reservoir Expansion is becoming known more for what's gone wrong than what's gone right.

But while the setbacks and environmental concerns shouldn't be overlooked, what they're trying to achieve here deserves recognition too.

Whether or not this is a good thing for Denver, Boulder County, or the whole of Colorado is clearly a contested topic.

But what can't be denied is that this is a feat of construction that truly raises the bar.

See how SkyOS is giving billions back and rebuilding the digital foundation of America’s physical industries here.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Denver Water, Carnegie Library for Local History Boulder, CBS, Denver7, Doka, FOX31 Denver, Lighthawk, Mitch Tobin, 9NEWS, Searchlight Pictures, Steve Riggins and The Water Desk.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.