Why America is Removing These Dams

- Youtube Views 1,656,658 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Masterworks.

DAMS are some of the world’s most impressive feats of engineering.

In the US, there are over 90,000 of them that generate electricity, control flooding and supply water to surrounding communities.

Like the four dams along the Klamath River stretching across the Oregon-California border. But there’s a big - wait for it - dam problem. These structures aren’t so great for the river’s fish and water quality.

After over a decade of debate over money, ecology and salmon, officials called for a drastic move: the demolition of all four dams.

It'll be largest river restoration and removal project that's ever been done.

Now if you thought that building a dam was tough, wait until you hear how you tear one down.

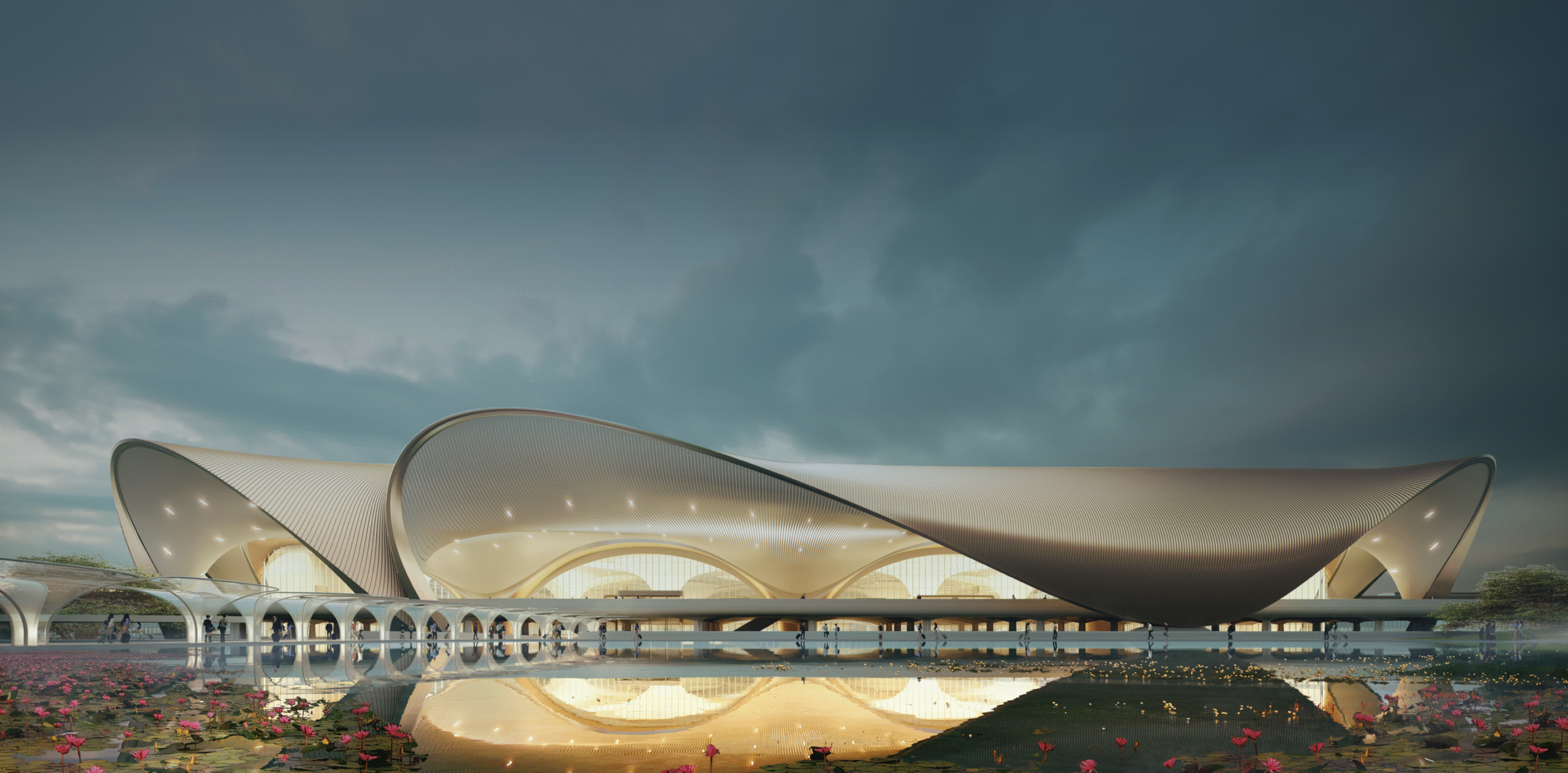

Above: The Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River. Courtesy of Michael Wier / CalTrout.

The Klamath River is known for its stunning scenery and wildlife, flowing more than 400km through parts of Oregon and California and drains a basin covering 31,000 square km.

At one point, the river was home to the third largest salmon population on the West Coast, providing a vital resource to local indigenous groups. But that all changed following the construction of hydroelectric dams on the river in the early 1900s.

From around 1895 to 1915, breakthroughs in hydroelectric design led to the construction of many new dams and power plants – like the ones in Klamath.

Today the dams produce enough energy to power 70,000 homes at their peak, though they usually aren’t operating at full capacity because of low water levels and other issues.

And like any major infrastructure project, there’s always a tradeoff.

While the structures have prevented potential flooding, provided tax revenue and recreational activities - they’ve also blocked the fish from reaching spawning habitats upstream.

Because of this, the salmon population has dwindled to less than 10 percent of its original volume.

Now experts worry the Klamath salmon are on the verge of extinction, which not only affects the local tribal groups, but the wildlife who depend on the salmon too.

This isn’t the only impact of the dams. During the warmer months, the water's are frequently plagued with toxic blue-green algae blooms, which occur when nutrient rich water gets trapped in the shallow reservoirs.

Environmentalists and local tribal groups have long fought to find a solution, while some homeowners worry removing the dam will cost them tax money and lost property values.

In the end, PacifiCorp, the energy supplier itself, said removal would be cheaper than the alternative of building fish ladders, and that the electricity the dam generated could easily be replaced.

And in 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission officially authorised the $450M removal of four major dams. Copco Dams 1&2, JC Boyle Dam and Iron Gate Dam.

No dam project of this size have ever been torn down before – and it’ll require meticulous planning and construction work to be done correctly.

There are two methods to remove a dam: instantaneous or staged.

Instantaneous removal happens quickly. Think hours or days.

Here a reservoir drawdown takes place, which is a process that involves releasing the water and built up sediment stored behind the dams downstream.

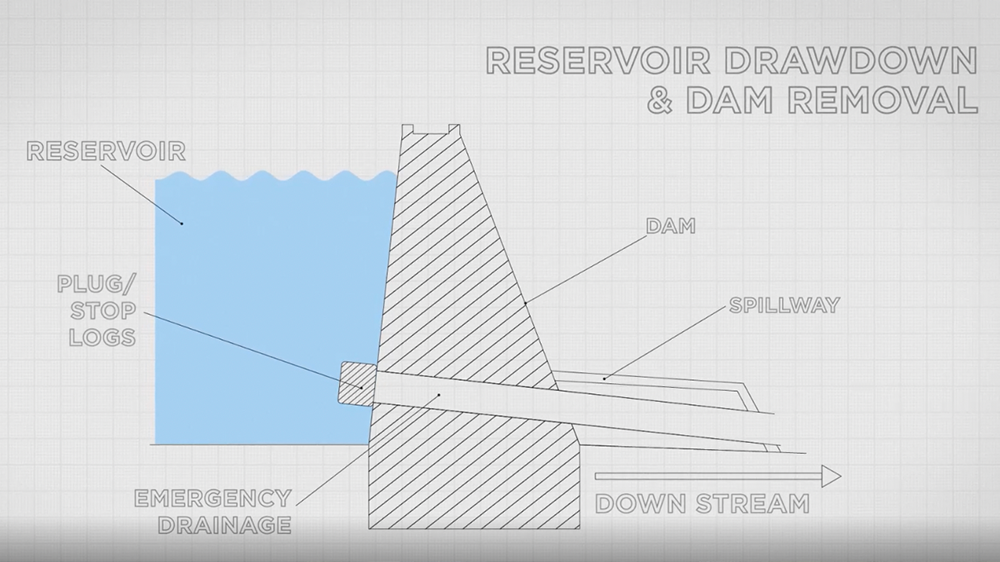

Above: This is what a typical design of a dam might look like.

Now, most dams have an emergency drainage system in case the water level needs to be lowered quickly.

This is usually in the form of either a low level conduit, which is just a channel that can be opened for water to flow through or a stoplog, which is essentially a stack of logs or beams that can be raised to let water through.

Once the water is released downstream, the dam itself is demolished with explosives and the rubble is removed from the site.

Staged removal happens over a longer period of time - usually months or years.

This method is reserved for taller dams with larger amounts of built up sediment that would pose environmental risks if released too quickly.

To do so, rivers are pumped or diverted away from the construction site through tunnels or channels, allowing for more control during the reservoir drawdown and sediment release.

Once the rivers are diverted and the basin is dry, the dam is demolished using tools like excavators or explosives.

This longer staged method is the basis for the Klamath dam removals, with slight variations depending on size and materials of each one. This will ultimately return the river to free-flowing condition.

Starting in 2023, Copco No. 2, the smallest of the four, will be the first dam to undergo demolition using the drill and shoot method - followed later by the other three.

"We will actually get underway with the drilling of a brand new ten foot diameter tunnel through the base of the dam in the fall of this year," Klamath River Renewal Corporation CEO Mark Bransom said.

"There are a series of box culverts underneath the concrete spillway that have stop logs, then concrete stop logs at the upstream end of the dam. And when we're ready to initiate the drawdown at boil will simply blast out those stop logs."

Unlike the others, Copco No. 2 has no real reservoir, so drawdown of it won't be needed. But this will be a necessary step for the remaining dams.

In early 2024, crews will open up low level outlets for the rest of the dams to slowly initiate drawdown of water and sediment at a rate of 1.5 metres per day.

Scheduling this during the winter is advantageous as it is the most biologically dormant time of year, so any sediment released into the water is expected to have the least amount of potential impact.

"The amount of sediment that we imagine and expect from the modelling will be introduced and flushed through the river is essentially equivalent to what the Klamath River transports on an annual basis," Bransom said.

The three remaining drawdowns will take place at the same time to take advantage of the water power to help mobilise and push the water through.

Above: An aerial shot of Copco Dam No. 1. Courtesy of Michael Wier / CalTrout.

The river will then be diverted through new or existing diversion tunnels from the original construction of the dams. This causes the channel to dry up, allowing for a safe demolition of the dams.

Now dam removal itself is only part of the equation. Following drawdown, a 2,200 acre footprint behind the dams will remain, that will be in need of restoration through the establishment of native vegetation and enhancement of habitat for the return of the salmon.

The scale of this dam removal is unprecedented, and it hasn’t come without its controversy. There’s no doubt the complexities of the demolition and restoration require a massive effort from managing entities.

But while it may be the largest effort in US history, it doesn’t mark the first dam removal.

In fact, the project is actually part of a larger removal trend happening across the country. In 2022 alone, 20 states tore down 65 dams in an effort to reconnect streams and rivers.

Now to be clear - not every dam needs to be torn down- there are several that still provide their intended purpose.

But as the decades go by, environmental standards change, unexpected impacts emerge, calling for their benefits to be reevaluated.

What’s happening here on the Klamath River shows the power of both construction, and deconstruction. Infrastructure has the ability to push technology forward and change the livelihood of millions of people.

While it’ll take years to see the effects of this dam removal, it’s a powerful reminder of how this industry is constantly evolving and adapting as the world continues to develop.

This video contains paid promotion for Masterworks.

Special thanks to Mark Bransom and David Coffman. Footage and images courtesy of Klamath River Renewal Corporation, News Watch 12, Resource Environmental Solutions LLC and ABC News.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.