Building the World's Tallest Megadam

- Youtube Views 1,431,192 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Straight Arrow News.

IMAGINE for a second if you built a dam to contain London. For a start, it would have to be incredibly tall.

This same dam would overshadow Paris, Singapore, and… well, actually, most cities.

This is what the poorest country in Central Asia is attempting to do. And, if successful, it’ll be the first country in history to pull it off.

Tajikistan is building the world’s tallest dam.

At 335 metres high it will generate power equivalent to three nuclear reactors. Not only will it solve the country’s energy crisis, it has the potential to radically transform the region and lift its people out of poverty.

But this has been in the making for a long time. And we mean a very long time.

Because the world’s tallest dam is actually a Soviet megaproject. Construction began in 1976, and now, half a century later, it’s finally being finished.

Soviet megaproject

Say the words “Rogun Project” to anyone in the former USSR and you’ll conjure up an almost mythical image.

Like the Palace of the Soviets that almost came to be… but instead of in Moscow, this Soviet feverdream was in the rural mountains of Central Asia.

But what do we mean by Soviet megaproject? Well, the USSR was famous for launching absolutely enormous construction projects. Often in extreme conditions and at immense human and financial cost.

Whether it was a 227 kilometer canal in the White Sea dug largely with prison labor, a huge steelworks city modeled on the U.S. and built from scratch in the Urals, or some of the largest dams Europe has ever seen.

But unlike the Palace of the Soviets, many of these dams were actually built.

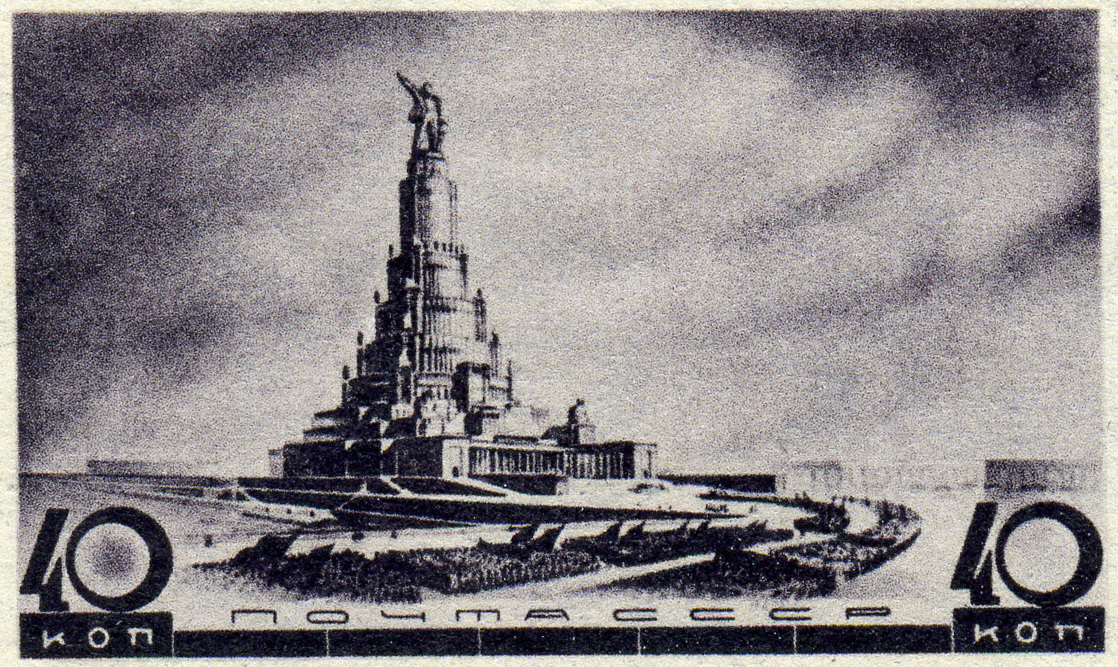

Above: The Palace of the Soviets on a postage stamp. The building was never completed.

They included the Volga Hydroelectric Station in central Russia, the Bratsk Dam on the Angara River in Siberia, and, yes, plans for the Rogun Dam in what is now Tajikistan.

But the Rogun dam would never have been possible without the innovation and engineering might that these other dams brought.

The Bratsk Dam in particular. At 125 metres high it was nearly as tall as a skyscraper itself, and the Bratsk Reservoir behind it is one of the largest man-made lakes in the world.

The reservoir stretches for 5,400 square kilometres, making it larger than some countries. But hey, it’s not like they’re short of space in Russia.

Bratsk dam is located here, deep in remote Siberia on the Anfara River.

Construction began in 1954 and at its peak employed 40,000 people. A new city, Bratsk, was built from scratch to house the workforce.

The dam was a concrete gravity dam and was designed so that its own weight would resist the pressure of the water.

A gravity dam holds back water because it’s so massive that the horizontal pressure of the reservoir physically cannot push it over or slide it downstream.

Think of it like a giant wedge of concrete anchored in rock:

the heavier and wider it is at the base, the harder it is for water pressure to move it.

As is typical for Siberia, it was built under extreme weather conditions, with winter temperatures plunging below -40C.

Construction workers faced permafrost, intimidatingly long transport distances and complete isolation.

Concrete had to be heated during pouring to prevent freezing, and equipment was adapted for permafrost and the extreme cold.

Above: The Bratsk Dam in Siberia.

After diverting the river through temporary tunnels and coffer dams, the main dam was then built in blocks, about 26 to 30 metres wide.

Flooding the Bratsk Reservoir took several years and required the resettlement of 30,000 people as the surrounding villages and farmland were submerged.

Bratsk was soon called the “light of Siberia”. It motivated the country, and became the stuff of Soviet legends.

1976

It was in the wake of this success that the Rogun Project was launched in 1976, as part of the USSR’s push to industrialize Central Asia and expand irrigation and energy supplies.

You see, Central Asia had incredible deposits of oil, natural gas, uranium, and non-ferrous metals. And all of these were things the USSR needed to support its European industrial base, which at this point in time was beginning to stagnate.

The push into Central Asia included steel plants, coal mines, roads, railways… and the tallest dam in the world. But not the one you’re thinking of.

The Soviets actually built the tallest dam in the world once before, and they built it in Tajikistan too.

This is the Nurek Dam, completed in 1979. At 300 metres high it is roughly the same height as the Eiffel Tower. It was the world’s first “supertall” dam.

And it served as a precursor to almost everything the Rogun dam would face.

It was built on the same river in the same mountainous terrain.

Tens of thousands of villagers were resettled to create its reservoir. Construction involved tens of thousands of workers, including many brought in from other Soviet republics.

The dam altered local ecosystems and contributed to the USSR’s broader water mismanagement in Central Asia, famously linked, albeit indirectly, to the Aral Sea disaster.

It was a prestige project to show that socialism could bring progress to one of the Union’s poorest regions.

By all means, it was a success. Even after the collapse of the union the dam provided up to 90% of the country’s electricity.

It was natural then that the Soviets looked to build another, even bigger dam. Further up the river.

They envisioned this new dam would generate massive amounts of electricity. And, as a bonus, would control the Vakhsh River’s seasonal flooding and provide irrigation water for cotton fields in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

Its energy would feed not just Tajikistan, but also Uzbekistan and southern Kazakhstan, creating an integrated Central Asian grid. It would be a revolution. And we know how the USSR feels about revolutions.

Work began in 1976 with excavation and the building of a coffer dam, that is a temporary structure built inside the river that pumps out water to keep the worksite dry.

Then the project stalled. It was far too ambitious for its own good.

While they had managed to build the Nurek Dam, this new site on the Vakhsh River was extremely challenging: it had an unstable geology, extremely high seismic risk, and required the need for massive, expensive tunneling.

Above: The Nurek Dam was the tallest dam in the world before Rogun.

Early work revealed leakage and landslide risks and forced repeated design changes. By the 1980s, under Brezhnev and then Gorbachev, the USSR faced stagnation and limited resources for giant infrastructure projects like this.

The money went elsewhere: the ongoing Afghanistan war, the arms race, and the Chernobyl cleanup.

Central Asia, which was already seen as peripheral and not as important to the USSR, suffered from reduced funding and faded from view.

And even during the Soviet era, Rogun was controversial. Downstream republics like Uzbekistan feared the dam would give Tajikistan too much control over water flows critical for cotton irrigation. This made Moscow cautious about pushing the project too hard in the later Soviet years.

By the time the USSR disintegrated, construction was already behind schedule. Tajikistan, newly independent in 1991, inherited the unfinished dam but lacked the money, expertise, or materials to continue.

The giant project had been planned as an all-Union effort, needing equipment, funding, and workers from across the entire USSR. All of this vanished overnight.

Why the dam stalled

To make things worse, the country then promptly descended into a violent civil war right after independence.

The Rogun construction site was looted, equipment destroyed, and many engineers and workers fled. Any chance of any major progress after 1992 evaporated.

But then something happened at the turn of the millennium.

By the year 2000, the country was stabilizing, and the government was looking for ways to rebuild the economy.

Restarting Rogun promised energy independence and export revenue. It promised money.

The entire country suffered from blackouts and chronic energy shortages. Especially in the colder months.

Tajikistan had to rely on importing energy from its neighbours, Uzbekistan and Russia.

Around 90 to 92 percent of the country’s energy comes from hydroelectric power, which means that unfortunately, it’s highly prone to seasonal shortages. Most of Tajikistan’s rivers are fed by glaciers and snow in the Pamirs and other mountains.

In spring and during summer the normally snowy caps of the mountains in Central Asia melt. This water has to go somewhere and it swells the country’s rivers and fills the reservoirs, powering the dams.

But in winter these same mountains and glaciers freeze and instead of raining it mostly snows. There is then less water to power the dams.

The Nurek Dam tries to combat this by storing water to use in these seasons. But it is not enough.

Tajikistan was in dire need of another source of electricity. It needed the Rogun dam.

As luck would have it, around this time Russia was beginning to stabilize. The country was experiencing an economic upturn after a terrible depression. The 90s were officially over.

Russia, through companies like Rusal, the aluminum giant, expressed interest in financing Rogun because it needed cheap electricity for aluminum production. This spurred preliminary work to begin again on the megadam.

Above: Work begins on the Rogun Dam. Image Courtesy of WeBuild.

Unfortunately this didn’t last long.

But building the world’s tallest dam isn’t cheap, and the cost kept spiralling. At this point, in the mid 2000s, the price was in the tens of billions of dollars.

President Emomali Rahmon made Rogun a national symbol, even encouraging citizens to buy shares in the dam, but it failed to generate enough funding.

Finally in 2016 Italian company Salini Impregilo, now Webuild, took over construction. And, boy, did they have their work cut out for them.

Back in 1993, the site suffered serious flooding which destroyed much of the existing construction works. The numerous earthquakes didn’t help matters either.

In fact, it was the Earthquakes that really scared the engineers.

How to earthquake-proof a megadam

Let’s pause for a second and really look at that in context.

The only structure comparable to this dam in height is a supertall skyscraper. Not a regular skyscraper, a city defining 300-metre plus skyscraper. Think... The Shard in London… or the John Hancock Center in Chicago… or Tokyo’s new tallest building The Torch.

Tokyo is another city where seismic activity is a key factor in the safety of a building. These supertall structures have to shake. But they have to stay standing.

Torch Tower can withstand violent earthquakes because of Base Isolation. This means its foundations decouple the building from ground motion. Instead of the whole tower shaking with the earth, the isolators absorb and slow down this seismic energy.

All throughout the skyscraper there are mass dampers. Essentially giant pendulums or tuned systems within the structure that sway in the opposite direction of the building and keep it steady.

All of these are ingenious solutions. None of them can be transferred to a dam.

A dam cannot be separated from its base. It has to be firm and solid and hold back thousands of litres of water, an almost unimaginable weight.

So engineers came up with a number of solutions.

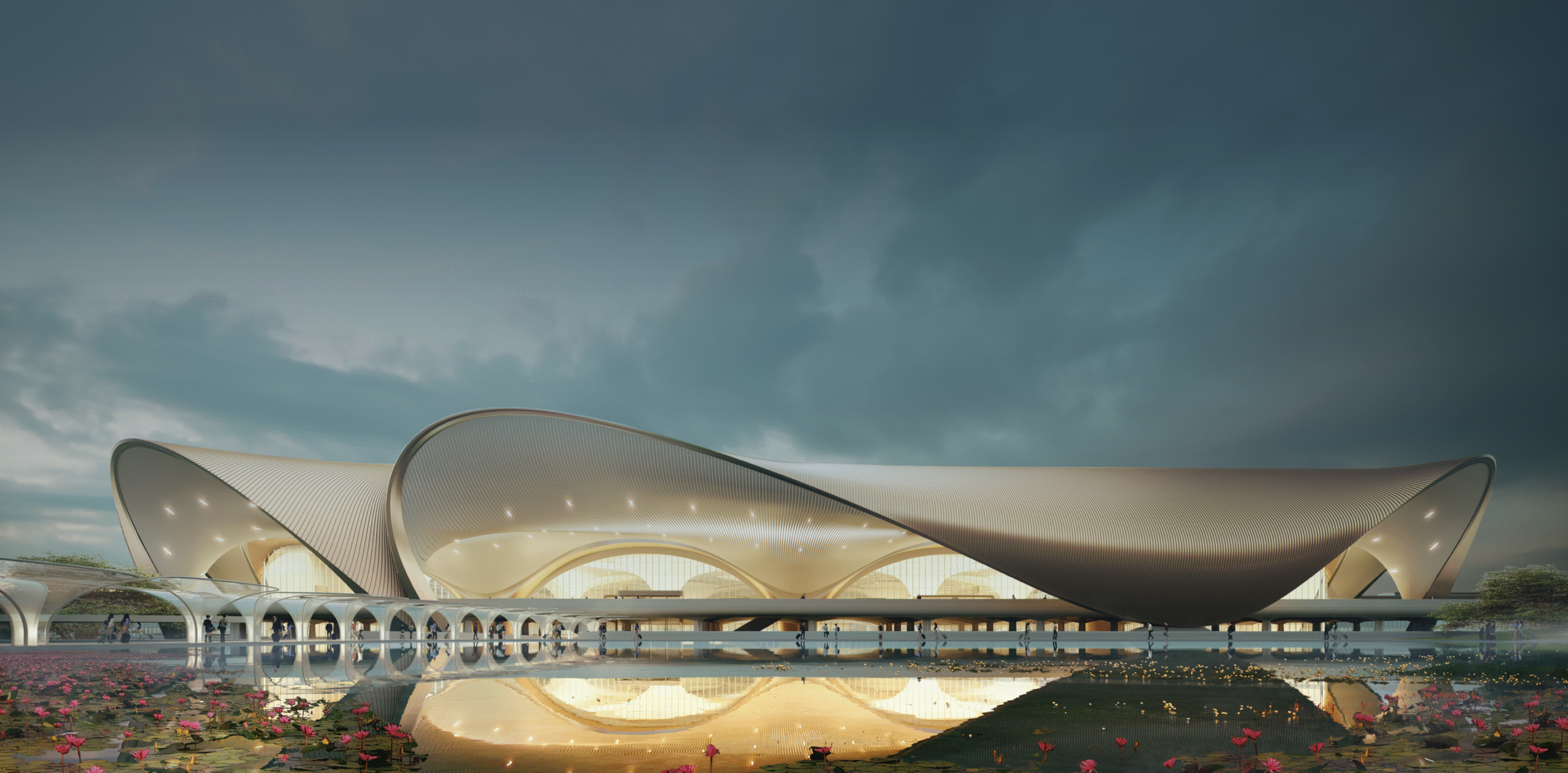

Above: The Rogun Dam will be the tallest in the world. Image courtesy of WeBuild.

Rogun is designed as a rockfill embankment dam with a central clay core. Unlike concrete arch or gravity dams, a rockfill structure is flexible, meaning it can be flexible in an earthquake without cracking.

The clay core provides watertightness, while the massive rockfill shoulders dissipate the energy from the earthquake.

This material behaves somewhat like a cushion: during an earthquake it can settle, compress, and shift without catastrophic failure.

The foundations of the dam have been reinforced to prevent liquefaction. This is what happens when soil loses its strength following a quake.

Emergency spillways and tunnels will also make sure the dam won’t be overtopped if landslides or quake-related blockages affect water levels. This is when the water in the reservoir spills over the dam wall.

And they really can’t overprepare in this situation - Rogun Dam is in a zone where quakes of magnitude 7 or even 8 are possible.

Diverting the river

Before building could even begin, engineering and construction teams had to divert the powerful Vakhsh River.

To build any large dam, the river must be diverted away from the construction site so workers can build on a dry foundation. WIth Rogun, this meant creating huge underground tunnels through the mountainside.

Four diversion tunnels were designed, each around 1.1 to 1.5 km long and about 11 to 15 m in diameter. Two were built on the left bank during the Soviet period, which engineers had to rehabilitate years later to ensure they were fit for purpose. They then completed two more on the right bank.

These tunnels act like giant bypass pipes, channeling the Vakhsh around the dam site.

By October 2016, Tajikistan announced the successful diversion of the Vakhsh River into the newly completed tunnels on the right bank. It was full steam ahead.

Once the diversion was in place, the riverbed at the dam site was drained. This allowed excavation down to bedrock so that the new rockfill embankment could be placed.

Constructing the dam

Construction began by carefully compacting layers of clay at the centerline of the dam site. This clay spine keeps water from leaking through.

On either side of the clay core, massive amounts of rock and gravel were dumped and compacted in layers.

The dam wasn’t built all at once. First, a starter dam was raised to a height of about 75 to 100 metres. This allowed partial impoundment of water and testing of systems.

Then, successive stages of rockfill and clay placement gradually increased the dam height.

Above: The Rogun Dam was built in tough conditions. Image courtesy of WeBuild.

By 2018, the water had risen enough for the first turbine to begin producing electricity.

The plan is for the dam to be fully complete by 2029, with the reservoir full by 2036.

In August 2025, it was reported that the dam’s crest had reached about 1,110 metres above sea level. That’s higher than Saudi Arabia’s future Jeddah Tower.

This is a major milestone, and close to the eventual full height, 1,300 m above sea level at crest. But there is still a large volume of embankment rockfill and clay core work to build.

While two of the six turbines are already commissioned and operating, one in 2018, another in 2019. Their production is not yet at full capacity.

Gradual filling of the reservoir is scheduled to begin once enough height and sealing are in place, but the reservoir won’t be at its full level until 2036.

The total cost to complete remains large, with estimates of around USD $6.2 to 6.4BN. The battle to secure that entire sum remains ongoing for now.

This dam has not been without its controversies.

Like the Nurek dam before it, once its reservoirs are full, entire valleys will be inundated and local communities will have to be displaced. 46,628 people in fact, from 69 villages.

As of 2024, over 15,000 residents have already been relocated.

This has resulted in loss of farming land and income for many people. And the new settlements are often less than adequate with limited access to schools and healthcare infrastructure.

Tensions with neighbouring Uzbekistan remain as well, with the country even hinting at possible conflict.

This isn’t the first time a megadam has sparked international chaos. The Grand Renaissance dam, the absolute massive megaproject in Ethiopia, has just been officially inaugurated and is now functioning. And down the Nile Egypt isn’t too happy about that.

The Rogun project has the potential to create conflict too, yes, but it could also achieve something miraculous. By exporting clean energy to neighbouring countries it could replace fossil fuels in the region.

These colossal projects reshape mountains, rivers, and even entire countries. There is a tremendous amount of responsibility on the engineers and decision makers to get them right.

Once you’ve built the world’s tallest dam, you can’t really go back.

Download the Straight Arrow News app by clicking here https://www.san.com/b1m to stay informed with Unbiased. Straight Facts.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Rogun Dam and WeBuild.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.