London’s Indestructible Nuclear-Proof Tower

- Youtube Views 729,132 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

On the eighth of October 1965 a single telephone call changed the history of London and the United Kingdom forever.

Over the last few years an enormous cylindrical tower had taken shape on the city’s skyline - taller than anything else in the entire country.

It was designed to withstand a nuclear blast.

And it didn’t appear on any maps. Officially, it didn’t exist at all.

This was the GPO Tower, or what we now call the BT Tower.

And that telephone call, made between then prime minister, Harold Wilson and the mayor of Birmingham, George Barrow, displayed for the first time its incredible power.

This strange, giant cylinder would connect a country that had been shattered by World War II.

Rebuilding London

The London of the 1950s and 60s was very different to the London of today.

Decimated by the Second World War, entire districts and neighbourhoods had been flattened by bombing. And the infrastructure that had survived was outdated and creaking under the demands of a rapidly modernising society.

The tallest building was still the 111m St Paul’s cathedral, which had remarkably outlived the Blitz.

Despite this, rebuilding London actually presented an incredible opportunity, especially as the city was undergoing a telecommunications revolution.

Once reserved only for the wealthy elite, telephones were quickly becoming essential for everyday Londoners.

On top of that, television, still a novelty during the war, was now a national obsession. As such signals had to travel further and faster. They also had to be more reliable than ever before.

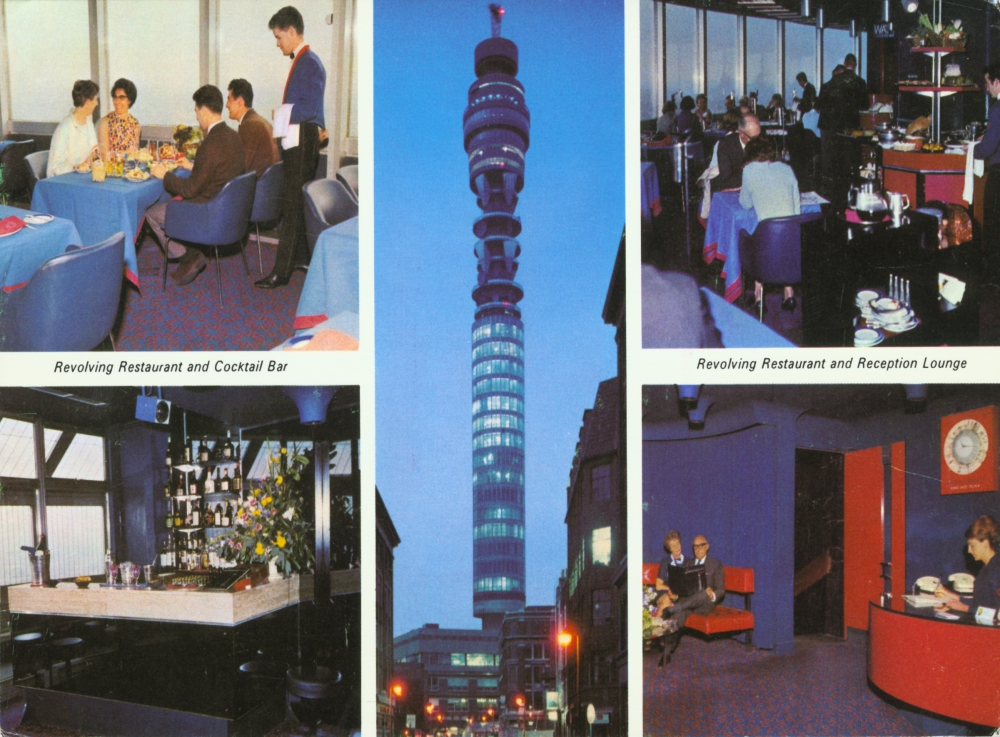

Above: An original postcard of BT Tower and the revolving restaurant. Image courtesy of BT Archives.

And all of this fell at the feet of… the General Post Office. The GPO oversaw not just all of Britain's postal services, but its telephone and television services too.

And it was buckling under the pressure.

Until this point, the UK had relied on traditional copper cables laid underground, but these were limited. Amplifiers were required every few kilometres, and laying new trunk routes through a city as dense as London was next to impossible.

Engineers were desperately in need of a better solution.

Microwave radio transmission changed everything. It meant that telephone calls and television pictures could be carried wirelessly all across the country.

There was just one problem. Microwave signals travel in straight lines meaning lines of sight between each transmission mast was required.

That meant that in a sprawling metropolis like London, engineers needed a tower tall enough to rise clear above the rooftops.

Building London’s tallest tower

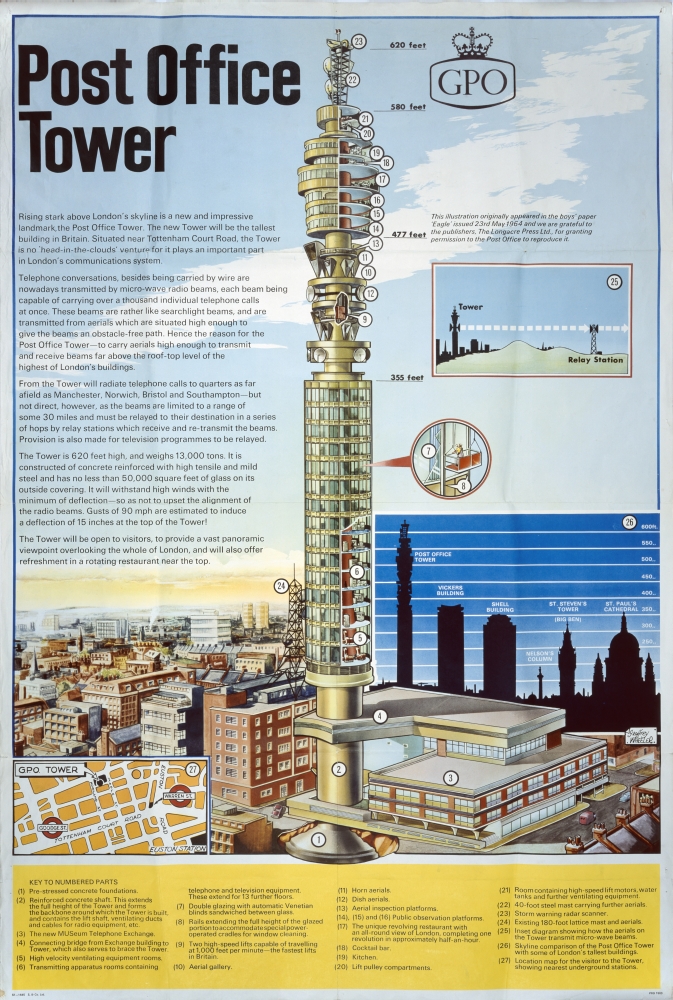

In 1955, Britain began planning a new trunk microwave network. Relay towers would be built across the country.

They would be in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Bristol, and beyond. In London would be a central node, tying it all together.

This node would house not only dishes, antennas, and offices but to help recoup the £2.5M to build at the time - equivalent to more than £60M today - it would also hold a restaurant.

At the time, engineers and architects alike knew that what they were designing was more than just public infrastructure.

By the very nature of its location and its scale, it would have to be a new landmark. A modern building for a modern Britain.

Enter Eric Bedford. He was the chief architect of the Ministry of Public Building and Works and was entrusted with the design of the tower. He was also the youngest to ever hold the position.

His proposition was daring: a cylindrical shaft of reinforced concrete, 177 metres tall. Vastly dwarfing anything that had ever been built in London - or the UK - before.

Unlike square or octagonal towers, this circular form offered the best wind resistance, ensuring that gusts would sweep around its surface rather than battering flat walls.

You see, this wasn’t just about style. It was about precision. For microwave dishes to function, they needed accuracy.

A structure that swayed even slightly could cause connections to fail. Bedford’s circular concept was, really, the only answer.

It was designed to shift no more than 25 centimetres in winds of up to 150 kilometres an hour.

To stabilise it, Bedford designed massive foundations. Unfortunately surveyors found the hard chalk that was needed to support these foundations was more than 52 metres below London. Too deep to be of any use.

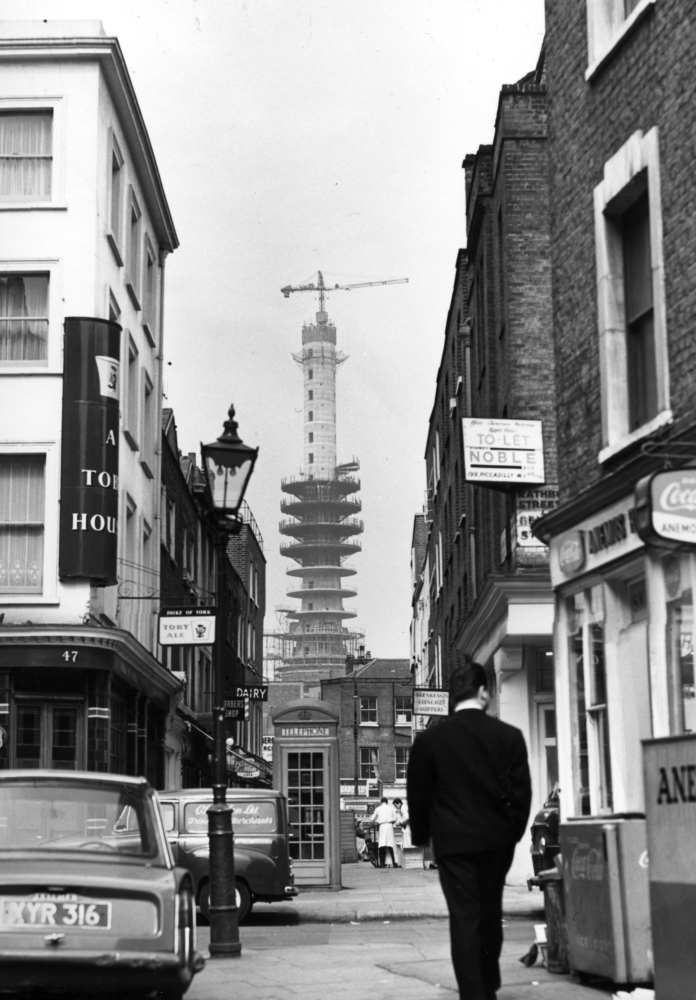

Above: BT Tower under construction. Image courtesy of BT Archives.

Instead, engineers sank a concrete raft 27 by 27 metres across and 1 metre thick, reinforced with 6 layers of cables.

A concrete pyramid was built on top of this raft which would then support the immense weight of the tower, which was more than 13,000 tonnes.

Inside, the tower’s core housed two high-speed lifts. Around them, thick concrete walls bore the vertical load.

Every few metres, protruding platforms held out the heavy microwave dishes.

Work began in June 1961, and Londoners soon noticed the strange cylinder rising steadily above Fitzrovia.

The construction method was cutting-edge for its time. Built using a combination of a climbing crane and a specialized climbing formwork system to construct its core, a method that was a predecessor to modern systems we use today.

A crane at the very top lifted materials and climbed with the tower. While for the concrete core, once a section hardened, the formwork was jacked up, and another pour began.

This allowed the tower to rise quickly and safely. A week-by-week ascent that became a spectacle in itself.

By 1963, the tower had reached its full height. Standing above the rooftops, it was already the tallest structure in London. But the work was far from done.

Steelwork for the upper levels was lifted into place by cranes perched hundreds of feet above the ground.

A terrifying task in the days before modern safety harnesses and regulations.

The microwave dishes were installed on cantilevered platforms. Each dish was up to 4 metres across, built from aluminium with protective covers.

They were precisely angled to connect with relay towers across Britain, forming a national web of microwave beams.

The central node was complete.

A strange new icon

At its peak, the tower bristled with more than 50 dishes, giving it the appearance of something out of the future.

The Post Office Tower was officially opened on October 8th, 1965, by Prime Minister Harold Wilson.

Its dominance of the skyline was unmatched. Visible from across London, it became an instant landmark, surpassing even the chimneys of Battersea Power Station.

For engineers, it represented the future of communications.

Television pictures, telephone calls, and data all flowed through the tower. It was, in every sense, the beating heart of Britain’s new communications network.

But for the public, it was the revolving restaurant that captured the imagination.

Located on the 34th floor the restaurant completed a full rotation every 23 minutes, offering diners panoramic views of London.

It quickly became one of the most glamorous venues in the city.

But behind the glamour, there was a darker reality. The Post Office Tower was also a piece of Cold War infrastructure.

Its microwave links were vital for defence. In the event of war, signals from government, military, and emergency services would be routed through the tower. That made it a prime target.

This meant the tower could not appear on any official maps and parliamentary questions about it were stonewalled.

It was even an offence under the Official Secrets Act to photograph it in certain contexts.

Above: A newspaper clipping from when the tower was completed. Image courtesy of BT Archives.

The tower had other secrets too.

Unlike many skyscrapers of its era, it was built with an unusual brief: to withstand the unthinkable. A nuclear strike.

Its narrow cylindrical form, apart from reducing wind loads, was also designed to lessen the impact of a blast wave.

The heavily reinforced concrete shaft at its core could remain standing even if much of the structure around it was obliterated.

Communications equipment was tucked away deep inside, shielded by concrete and steel, ensuring that Britain could stay connected in a time of crisis.

Of course, this is all relative. A direct hit would reduce even the toughest structures to rubble. But the BT Tower’s design meant it could endure the peripheral shockwaves of an attack better than most.

Inside the tower itself, life was more functional than glamorous. Floors housed racks of equipment: microwave transmitters, amplifiers, switching gear. Engineers worked around the clock to maintain the system.

The lifts were among the fastest in Europe, taking staff and visitors to the top in under 30 seconds.

Power was supplied by multiple feeds, with backup generators to keep communications running… in any emergency.

Above: The tower was soon made obsolete. Image courtesy of BT Archives.

People who worked there described the tower as a world of its own.

Its resilience was tested on October 31st, 1971 when a bomb planted by the Provisional IRA exploded in the restaurant toilets on the 31st floor.

The blast caused significant damage and injured several people. Though the restaurant reopened briefly, the sense of risk remained.

In 1980, it closed permanently. From then on, the tower’s role as a public attraction faded, and its communications function became its primary identity.

But the very reason the tower was built soon became its biggest problem.

Soon obsolete

By the 1980s, new technology was emerging. Fibre optic cables could carry far more data, more reliably, and without the line-of-sight limitations of microwave signals.

Within a generation, the tower’s original purpose was obsolete. The dishes were stripped away, leaving a cleaner silhouette but also stripping the tower of its purpose.

Today, it’s far from London’s tallest building, yet its height is still impressive compared to its surroundings.

Above: The tower when completed in the 1960s. Image courtesy of BT Archives.

What’s unique about it is that unlike the city or Canary Wharf, BT Tower stands remarkably alone. There’s no cluster of skyscrapers here.

Planners have resisted high-rise development in Fitzrovia to avoid blocking sightlines to and from the tower.

If tall buildings had been constructed nearby, they would have blocked its signals.

For decades, that alone was enough to limit development in the area. Even after the dishes were removed in the 2000s and these lines of site were no longer needed, that planning legacy has remained.

Now, travelling up the tower today you can see some truly remarkable, uninterrupted views of the entire city of London.

Which makes it perfect for its new purpose… a hotel.

BT sold the tower to MCR Hotels, an American company that has partnered with Heatherwick Studio to transform the icon.

Heatherwick is well known for its ambitious, often sculptural work. The studio designed New York’s Vessel and Little Island. Their reimagining of BT Tower will no doubt be just as impressive, and unexpected.

There are of course numerous challenges they will face. The least of which because BT Tower is Grade II listed, meaning its historic and architectural character is protected. Any major changes have to respect that heritage status.

The tower cannot be easily destroyed either, if it can survive a nuclear blast it can survive modern London developers. Meaning, it can’t just be demolished to make way for a shiny new skyscraper.

But maybe that’s a good thing. Modern cities can be quick to write off old buildings, especially those made in the middle of the 20th century that dare to be modernist or, god help us, brutalist.

However the future may shape it, this indestructible cylinder is a towering monument to post-war Britain and its indestructible spirit.

Additional footage and images courtesy of BT Tower Archives.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.