The Philippines’ $15BN Gamble on a Sinking Airport

- Youtube Views 1,951,586 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated by Fred Mills.

ONE of the largest airports in the world is being built in the Philippines.

Twice as big as JFK International and nearly three times bigger than Sydney Airport, New Manila International will engulf a staggering 2,500 hectares of land and once complete, it’ll be ready for 100 million annual passengers.

The problem is that within 30 years, sinking land and floods could render this $15 billion project defunct.

Why build it?

In its bid to lead the way for Southeast Asia, the Philippines is taking an enormous gamble on NMIA, or New Manila International Airport.

The nation’s biggest and busiest airport, Ninoy Aquino International, is completely oversubscribed. Last year it welcomed 50 million people through its terminals - that’s even higher than pre-pandemic numbers.

But Ninoy Aquino wasn’t designed for this level of traffic. In fact, it was only meant to handle between 35 and 40 million passengers each year and that’s led to this airport gaining a reputation for major crowding and delays.

Above: Ninoy Aquino Airport has gained a reputation for crowding and delays.

When airports run into this issue, they often go for expansion to solve their problems. It’s a lot simpler to keep the main logistics hub in one place - not to mention a heck of a lot cheaper than building a whole new airport.

But there’s a problem - Ninoy Aquino is completely locked in.

It’s surrounded by thousands of homes split into barangays and in a city as densely populated as Manila, rehoming this population is pretty much out of the question.

In fact, Manila is so densely populated, if you want to find a new spot for an airport you have to get creative - which brings us to Manila Bay.

An airport on the water

The land for this airport is being raised from the sea. Expressways and rail line connections, currently under construction, will lead to NMIA including two separate toll roads measuring eight and 18 kilometres each.

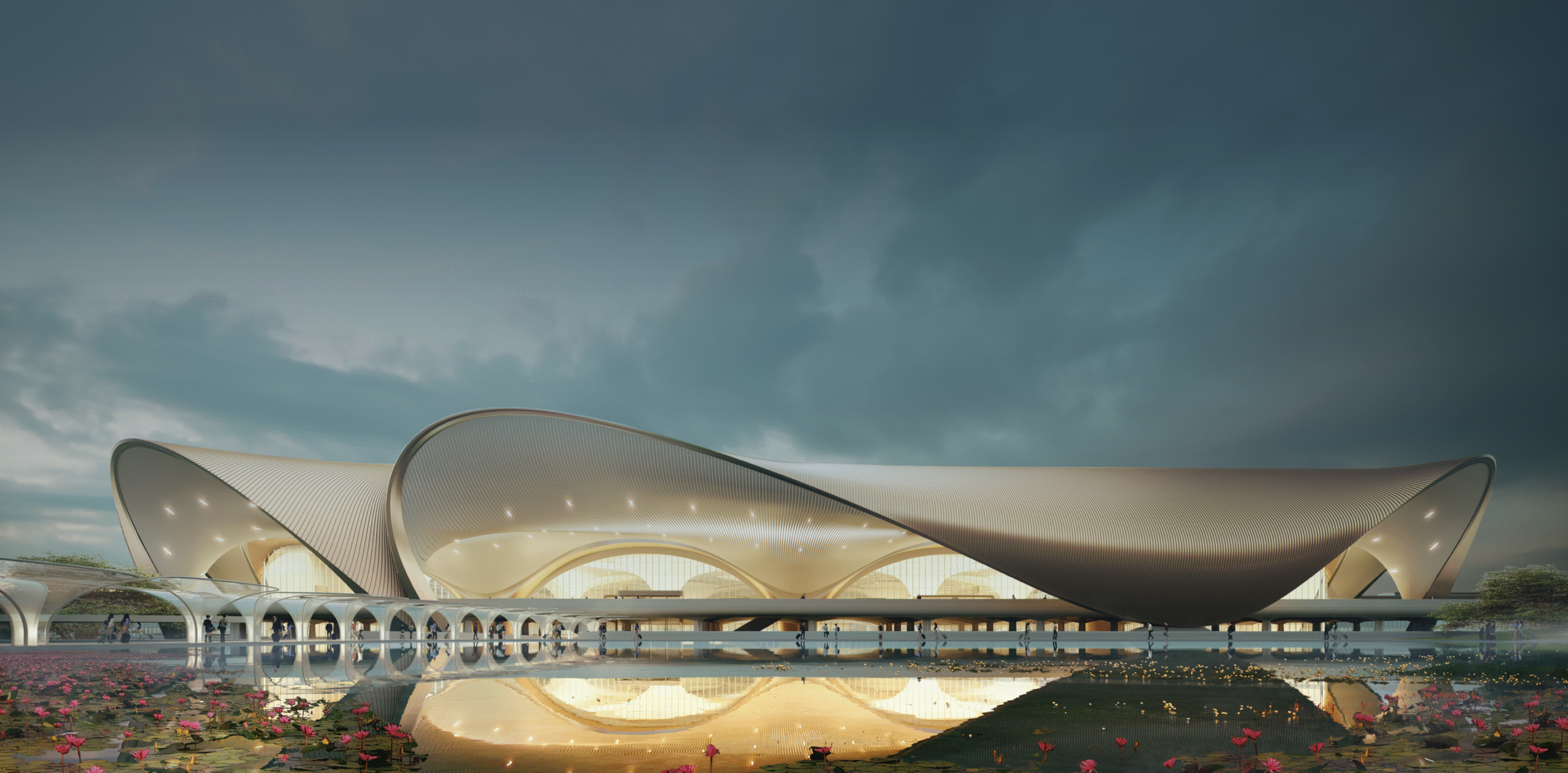

Follow those roads to the airport and you’ll experience a passenger terminal big enough to take your breath away.

Above: New Manila International Airport will feature one, enormous passenger terminal capable of handling 100m people each year. Courtesy of SMC.

A lot of modern, large-scale airports feature multiple terminal buildings to help filter passengers but not here.

A whopping 100 million travellers a year will go through a huge, singular facility spread across 350,000m2 - that’s equivalent to about 70 White Houses - and it looks spectacular.

While there’s only one passenger terminal, airports are about more than just travellers. A huge amount of money is made from freight and so a cargo terminal will be constructed spanning 52,000m2, fit to process more than half a million tonnes of cargo every year.

But visually, there’s no denying the passenger terminal steals the show with six concourses attached to the main hub and in time, four runways ranging from 2,600m to 3,500m will be laid, set for a reported capacity of 240 aircraft every hour.

For context, Ninoy Aquino processes about 40 aircraft per hour, Heathrow processes near 60 and the world’s busiest airport, Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta, processes on average nearly 100 aircraft every hour.

The vision for New Manila International is bold, right down to its foundations.

Go back four short years to 2021 and this site was just sea and fields but it's gone through a dramatic transformation. A massive footprint of land has been developed using 150 million cubic metres of borrow material which is a mix of sand and sediment collected from around the world.

Above: A huge footprint of land has been created to host the new airport. Courtesy of Global Witness.

There are a few different ways to do that, all centring around a few key principles.

For New Manila International, the Dutch dredging company, Boskalis employed a selection of vessels known as dredgers to act like hoovers and suck up sand from one location and transport it to another.

Once the sand was deposited into Manila Bay, Boskalis went about preparing the land.

However, the problem with dumping sand and sediment into the sea is soil liquefaction. The material saturates with water, which makes the base unstable - not ideal for something as heavy as an airport.

Boskalis’ solution is called dynamic compaction, a process in which 10 to 20 ton hammers are dropped repeatedly from 10 to 25 metres high.

That compresses the soil, displacing any water within and making it a sturdier surface to build on, a bit like squeezing a sponge.

Earlier this year it was reported 80% of the land had already been prepared but that’s behind schedule and the blame goes back to borrow material.

By nature of the name, the sand used to create these foundations comes from elsewhere and Boskalis ran out.

The stuff we built our sand castles out of as kids is actually an incredibly hot commodity - behind water, it's the most consumed natural resource on the planet.

Nearly seven billion tons of sand and sediment are dredged from our seas around the world each year but as massive as those reserves are, they’re limited.

Sand is used for everything from concrete, mortar and glass to your more obvious applications like golf course bunkers and playground sand pits.

Worldwide demand has turned into a vicious war with people killed in the struggle for this material.

Riverbeds and beaches are being stripped as developers search for more and more and once Boskalis ran out of sand from the original site, the project had no choice but to halt, delaying the opening date by a year.

Work is now back underway on the final sections of land development but that’s just one of a number of controversial hurdles to cross.

Is it doomed?

As with any megaproject, the next problem is only ever just around the corner and in the case of this airport, it comes in the form of sinking land and floods.

Assessments carried out by the airport’s developer, SMC, predicted sea levels will rise by about 5.3mm per year up to 2050.

But a variety of experts, including Olaf Neussner, a Disaster Risk Reduction Consultant in the Philippines, says that figure is completely undercooked for the region.

“My take would be you should take the worst case scenario to see what you’re expecting but the feasibility study went the other way, they took the most optimistic data. There is an average of sea level rise in the whole world and this is in the range of 5mm per year but it’s not the same all over the world. The measurements in Manila Bay are much higher."

His estimate is much closer to somewhere between 13mm to 15mm of sea level rise each year, nearly three times higher than SMC’s verdict.

If you’re wondering how the sea level could be higher in one area than another, it comes down to currents and temperature: a process called sterodynamic sea level change.

Ocean currents transport heat around the planet via the sea but as the ice sheets melt, more freshwater is created, changing the sea’s density and temperature. In turn, that changes the speed and location of where currents carry water.

It means any coastlines close to melting ice feel less of an impact from sea level rises than countries further away and when you couple that with storm surges, characterised by an abnormal rise in sea levels due to high winds and low atmospheric pressure, you have a problem.

Manila sits in a typhoon region that faces powerful tropical cyclones and Bulacan, where the airport is being built, is one of the top-10 flood prone areas in the country.

“Rain patterns are changing towards drier dry seasons and wetter wet seasons", said Neussner. "That means you might have droughts when you don’t want them and you might have too much rain and then floods so the most likely scenario is increased floods in some areas including of course Manila or the new airport area.”

Manila Bay and all coastal areas in the Philippines sit along the Pacific Ring of Fire, a zone of high seismic activity and that means earthquakes and tsunamis are much more likely.

New Manila International Airport is being constructed in a proverbial bear pit and it’s not like land reclamation guarantees granite-like stability.

The ground should be sturdy enough to build on top of but preparing for an earthquake is a different ballgame.

Part of the issue is that Manila Bay features thick layers of very soft clay and loose sand - a nightmare for liquefaction and soil movement.

To slow the sink and protect the land, engineers have a few tricks up their sleeves, starting with rock revetments. They line the site like a large boundary wall with sloped sides to defend against tidal deterioration.

The land underneath where the airport will sit is then fitted with geogrids that act like ribs to improve ground stability, while deep cement mixing or prefabricated vertical drains target the clay like layer.

But it doesn’t stop there: to really condense the sand, horizontal vibrations and fluid penetrate through the ground to reduce soil friction and densify the layers, a process known as vibroflotation.

There are mitigating devices to strengthen the ground but that doesn’t protect the airport from flooding so the land mass will rise to a height of about four metres.

The problem is that Global Witness reports the engineering assumptions are excessively optimistic. If experts are to be believed, flights could be grounded and runways covered in water within thirty years - that’s if ground sinking doesn’t cause greater issues first.

Severe environmental damage caused to the ecosystem in Manila Bay, one of the most important coastal areas in the country, has been labeled as potentially irreversible - just to add to the controversies.

SMC will point to a commitment to plant new mangroves and a platform for migratory birds but scientists say the wrong species of mangroves have been planted.

There’s also the impact of displacement as Francisca Stuardo from Global Witness explains:

“Over 700 families and around 3,000 people will be directly impacted by this airport by being displaced, some of them with little or no compensation and it has a trickle down effect because it’s not only the families displaced but the communities. Their livelihoods depend on the coastal areas where the airport will take place.”

We’ve talked a lot here about land reclamation and the ways in which New Manila International is being created but according to the developer, this isn’t land reclamation at all.

They’ve labeled the project a land development, seemingly bypassing strict government controls over creating new land in the sea and while you can clearly see some preexisting land where the project began, the sheer amount of sand dredged and dumped makes the argument a difficult sell.

SMC hasn’t responded to The B1M’s request for comment.

Despite the odds, New Manila International continues its development. Construction of the airport itself is set to begin in 2026 and roadways to the site are well underway.

Above: A render of the passenger terminal at New Manila International Airport. Courtesy of SMC.

The whole project is just one piece of a wider vision to create a 12,000 hectare city featuring houses, government buildings, a seaport and an industrial zone and while the old saying rings true that you need to spend money to make money, at $15 billion this project feels like an enormous gamble.

If all goes to plan, this could be one of the most impressive airports anywhere on the planet but if you listen to the experts, New Manila International could be in for some serious turbulence.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Global Witness, Lights On You, SMC Infrastructure, ANC 24/7, MNL.FLIGHTS, ElectricTV, Just Ozed, Kelly, Basilio Sepe, Tom Fisk, Kindel Media, Sky Sports News, US Gov, Guardian News and Palafox.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.