Will There Be Another World's Tallest Building?

- Youtube Views 1,837,115 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

FROM the Tower of Babel to the pyramids, St Paul’s Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, and, finally, that great 20th-century invention, the skyscraper - we’ve always yearned to touch the sky.

The skyscraper is both a symbol for mankind’s limitless ambition and an immensely practical and profitable solution to our increasingly urbanised lives.

However, the economics of the skyscraper has long been a contentious subject.

Building higher can increase revenue, as each additional floor creates opportunities for retail, office and residential spaces.

For decades, conventional wisdom said that 63 storeys was the optimal height for a skyscraper. Building any less essentially leaves money on the table, while building higher risks overshooting construction costs leaving developers without a profit.

While 63 storeys may sound precise, it is, in fact, a rough figure that clearly depends on a variety of conditional factors - but it illustrates the argument: at a certain point, skyscrapers are no longer economically feasible.

Beyond that point, they cease their practical purpose and become something else.

Above: The Burj Khalifa officially opened in 2010, becoming the tallest building in the world.

This is no more apparent than in the race to build the world’s tallest building, where the limits of practicality knock against the expanse of human ambition.

The last century has seen the title change hands from building to building no less than nine times, but with the construction of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa in

2010 - a building that jumped more than 300 metres higher than its predecessor - we have seen that race cool, and perhaps end.

The Burj Khalifa is the first structure since Chicago’s Sears Tower to hold onto the title of world’s tallest building for longer than a decade.

In that time, competing projects to the Burj have come and gone, brought back down to earth by mounting costs and their own impracticality. The desire to be the tallest appears to be fading. Have we finally found the meeting point of hubris and economics? Have we built the world’s last tallest building?

The Burj Khalifa is an icon - and it was built to be one.

2020 marks a decade since the 828 metre-high tower officially opened - the culmination of five years of construction work from foundation to spire, more than 10 years of planning, and some 22 million man hours.

Above: Dubai built a number of extravagant tourist attractions in the late 90s and early 00s, including the Burj al Arab.

Plans for the tower first emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Keen to diversify its economy away from the oil industry and to leave its mark on the world, the small port city of Dubai began to invest heavily in creating tourist attractions and turned its eye to that most superlative of construction titles: the world’s tallest building.

At that time, a number of projects were attempting to overtake the reigning Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur.

The Shanghai World Finance Centre and the 508 metre high Taipei 101 were both already under construction, and the long-gestating World Trade Centre had ambitions to bring the title back to New York.

Dubai officials didn’t want to invest in constructing the world’s tallest building only for its record to be broken a few years later by another project.

They wanted to create a building so high that it would reign as the world’s tallest for decades.

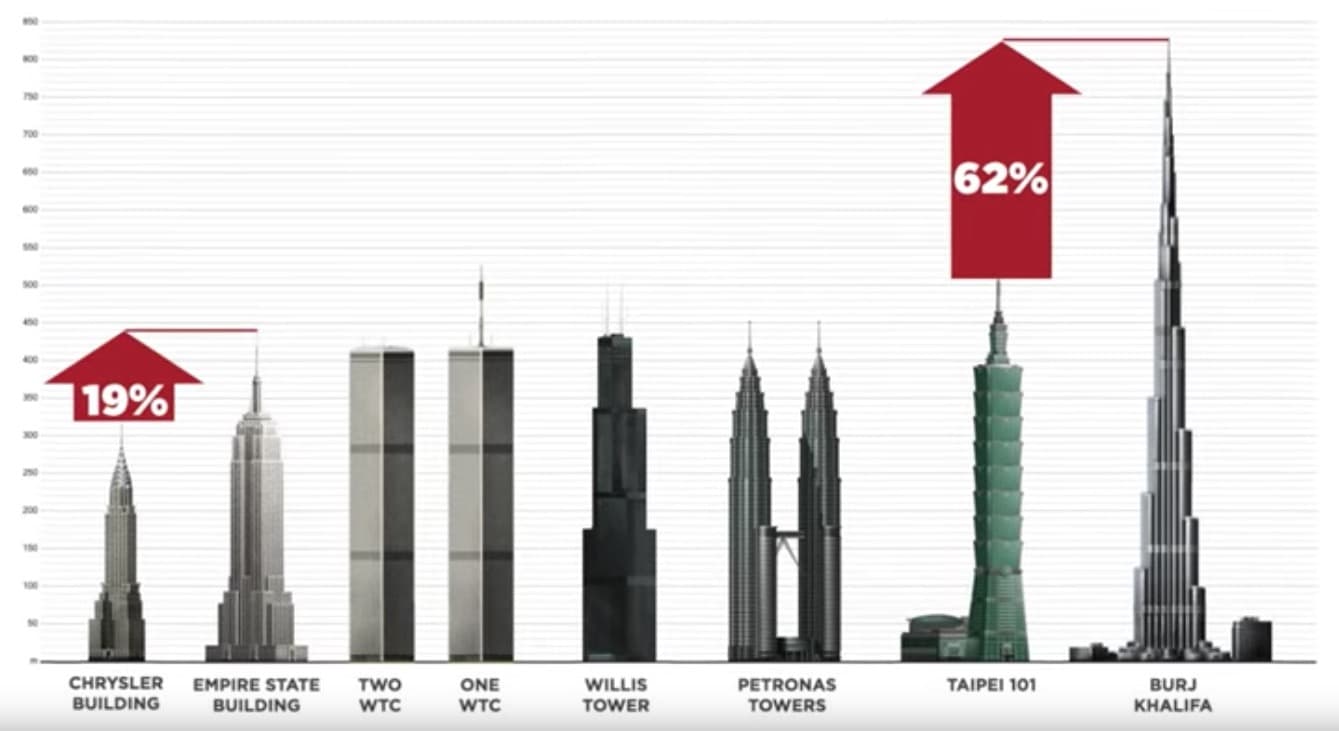

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill envisioned an unheard of 62 percent increase in height from the last world’s tallest. To put that in perspective, over the past century no other contender has gone higher than 19 percent - including the Empire State Building.

Above: The Burj Khalifa saw an unprecedented 62% increase in height from its predecessor (image courtesy of Skyscraper Page).

The construction of the Burj Khalifa was the result of a perfect storm; an alignment of critical components needed to create such a structure. Funded by a city eager to prove itself on the world stage combined with a near bottomless pit of money to draw from.

None of the usual requirements and restraints of practicality applied here, and no one questioned whether a city of little more than a million people needed a USD $1.5 billion skyscraper.

In the years since the Burj Khalifa’s opening a number of projects have sought to take its crown.

In 2013, the 838 metre Sky City skyscraper was proposed in China; an incredibly ambitious pre-fabricated project that would have been built in just 120 days. Foundations were laid, but safety concerns and a failure to obtain proper approval from the government pushed the project back and it stalled. The foundations are now used by locals as a fish farm.

China has had several other notable proposals. In 2014 there was the Suzhou Zhongnan Center which was also set to reach 838 metres. Construction stalled in 2015 and the project is now officially on hold.

Shenzhen also proposed an 830 metre tower as part of the Hubei Old Village Redevelopment, although construction has yet to start and the project appears to be stalled.

Above: The proposed Suzhou Zhongnan Center was scaled back then ultimately cancelled (image courtesy of Gensler, ECADI).

Saudi Arabia’s Jeddah Tower is by far the closest a building has come to taking the Burj’s crown.

The project shares a number of similarities with the Burj. Rising from a small desert city with aims to move away from an oil-dependent economy, and backed by a government with a near endless amount of money. The tower is even designed by the same architect and employs the same Y-shaped floor-plan as the Burj - an innovative technique used to offset wind loads.

The Jeddah Tower had plans to rise to 1000 metres - making it the first man-made structure to reach the kilometre high mark.

Construction started in April 2013 and was set to take just over five years to complete.

However, the project currently sits at a height of around 260 metres, with work appearing to have stopped sometime in 2018. There are several reports that the tower is officially on hold, a virtual kiss of death for a project like this.

Several factors have led to the scheme stalling, including the much-publicised anti-corruption purge of 2017 which claimed two of the building’s most prominent backers, growing costs and the shifting priorities of the Saudi government.

Not to be outdone, Dubai announced its own competitor to the Jeddah Tower with Dubai Creek Tower - a 1,300 metre high observation tower that would have dwarfed both Jeddah Tower and the Burj Khalifa.

While foundations were laid in 2017, no progress has been made since, and with construction on Jeddah Tower yet to resume there seems to be little motivation for them to continue.

Above: Dubai's answer to Jeddah Tower, the proposed Dubai Creek Tower (image courtesy of Santiago Calatrava).

So where will the next world’s tallest building come from?

The most obvious answer would appear to be China. They have money to spend, a vast urban population, and an eagerness to prove themselves on the world stage.

Yet, China’s cooling economy has seen a number of their recent mega-projects cancelled or postponed.

It is worth noting that taking away the Burj’s vanity height, the highest occupiable floor of China’s tallest building, the Shanghai Tower, is just two metres below that of the Burj’s. If the Burj did not have it’s nearly 200 metre high spire the towers would be approximately the same height.

While Shanghai Tower is an impressive architectural icon of modern China, the building has been plagued with an astoundingly low occupancy rate, crippling debt, and bureaucratic red tape that has delayed tenants who have been ready to move in for years. These problems are made painfully visible at night, when half of the tower fails to light up.

As such, China’s reluctance to invest in another mega-tall structure so soon after the failures of Shanghai Tower is perhaps understandable.

India also has ambitions to compete with Dubai - unveiling plans in 2017 for a new tower in Mumbai.

The plans were immediately met with an outcry from locals, who pointed to the country’s considerable socio-economic problems, much needed public infrastructure, and food and water shortages - all seen as far greater priorities than building a large skyscraper.

Building the world’s tallest building is now such an immense undertaking that it cannot be achieved by developers alone. That’s why, looking back over the last few decades in skyscraper construction, these remarkably tall buildings are no longer named after corporations, but after cities and countries.

The days of the Sears and Petronas Towers are gone. We now have Taipei 101 and Shanghai Tower. Even the Burj Khalifa’s original name was the Burj Dubai, before being renamed in honour of the ruler of Abu Dhabi.

Above: The former tallest building of the world, Taipei 101.

These projects require an enormous amount of money behind them, they also require the rewriting of local building regulations and flight paths. They need the unequivocal support and oftentimes the financial backing of their governments, otherwise they will never get out of the ground.

This perfect storm needed to create the world’s next tallest building - a booming economy, a near endless supply of money, a desire to be put on the world map, and unconditional support from the government - now has to match the immense height that Dubai has already presented to the world.

It was a lot easier to build a 500 metre plus skyscraper ten years ago than it is to build an 800 metre plus one now.

Currently, there isn’t anywhere in the world that has the financial backing and ambition to beat Dubai, and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill may have achieved exactly what they were asked to when first conceiving the Burj Khalifa: to create a world’s tallest building that would last.

So, will we ever build taller? Is this the end of the race? For now, it would seem so.

.jpg?Action=thumbnail&algorithm=fill_proportional&width=550)

Above: The Empire State Building was the tallest building in the world for forty years.

When the Empire State Building opened to the public 88 years ago, actress Fay Wray said: “When I’m in New York I look at the Empire State Building and feel as though it belongs to me… or is it vice versa?”

That is what great construction accomplishes. The Empire State Building was so tall, so grand, that it seemed almost impossible. It was unthinkable that anyone could build taller, and it took 40 years for its record to be beaten.

Why do we build tall buildings? Because we can. And when the time is right, when that perfect storm appears again, we will.

Narrated by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of 22 Bishopsgate, Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill, Santiago Calatrava, EMAAR Properties, Lienyuan Lee, Skyscraper Page, Broad Group, Gensler, ECADI, Goettsch Partners, Jeddah Economic Company, Bakhsh, S. Nitzold, Alejandro VN, Harmen Patil.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.