Why Colombia’s $4BN Dam Failed

- Youtube Views 16,715 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted and narrated by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Brilliant.

This is the city of Puerto Valdivia.

And it’s being evacuated.

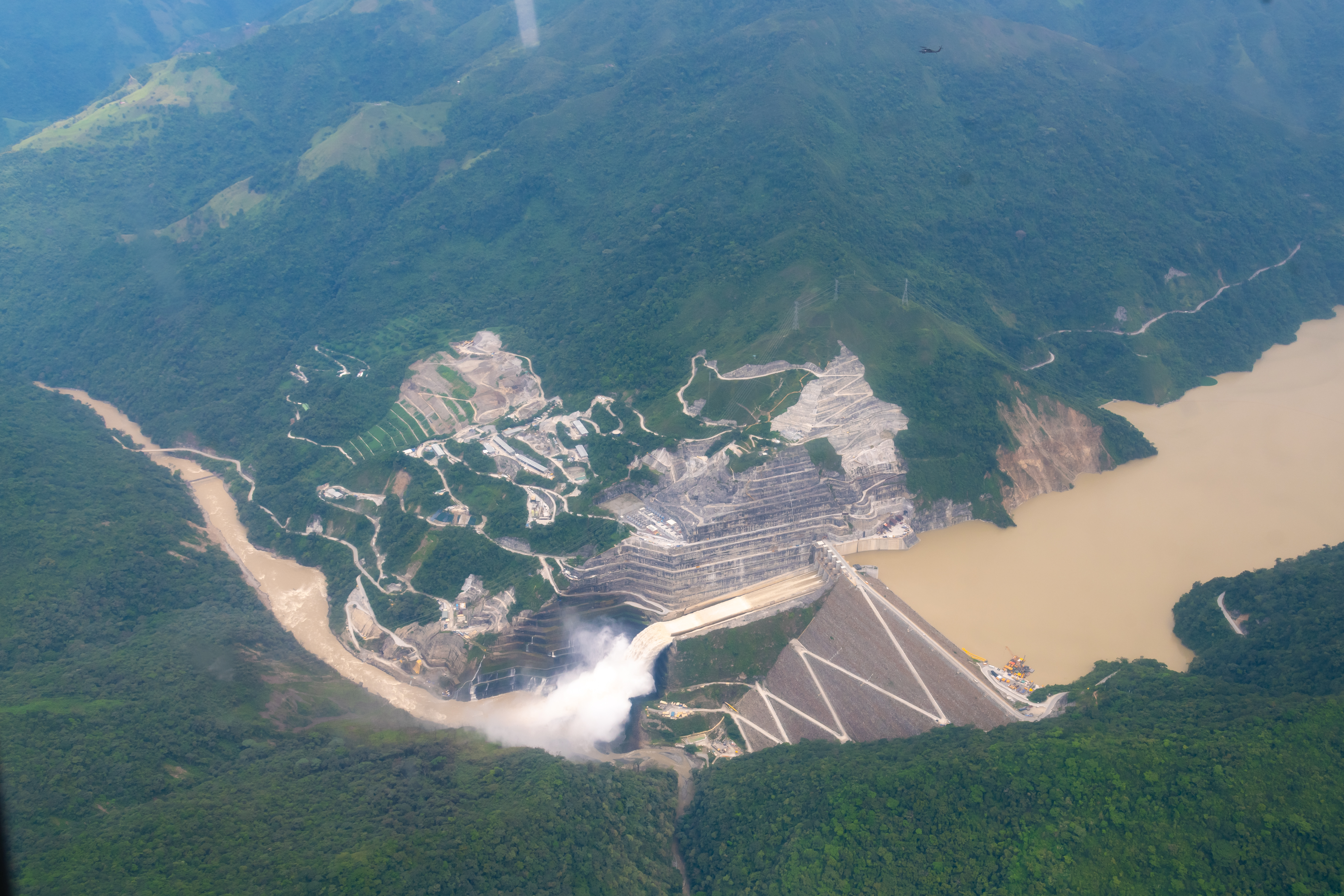

The largest dam Colombia has ever built is about to fail and the 25,000 people who live downstream need to get out of the way. Fast. This is the Ituango Dam, central to Colombia’s ambitions to become energy independent, and part of its massive infrastructure building boom.

It is 225 metres high - taller than a skyscraper. Behind it is a reservoir that can reach up to 127 km in length and hold 2.72 billion cubic metres of water. And it's all about to come tumbling down.

How did we get here?

Evacuation

On the 13th of May 2018 authorities sounded the alarm and evacuated at first just 600 residents of Puerto Valdivia. A few days later the entire city had to be abandoned and the residents of Puerto Valdivia moved to temporary shelters.

The flooding that came destroyed 59 homes, two schools, a health care center, critical infrastructure, and the city’s famous bridge. What was left became a ghost town. This mass displacement only exasperated existing social problems in a region already affected by violence and instability.

This was just a taste of what could happen if the entire project were to collapse. This was just the side tunnels.

Above: Downstream of the dam had to be evacuated.

If Hidroituango breaks, it would endanger the lives of the 120,000 people who live in the Cauca River Basin. Despite getting the all clear to return, few wanted to. The town was destroyed. More than 400 families were now homeless.

What’s worse is this wasn’t caused by some ancient dam in desperate need of fixing.

The Ituango Dam was brand new, due to be completed just a few weeks after disaster struck. This was supposed to be a modern, state of the art project to lift the country to a higher level.

Biggest dam ever

It was designed to be Colombia’s largest hydroelectric project, and eventually supply 17% of the country’s electricity. And that was power that Colombia desperately needed.

The two decades prior had seen a swell in the country’s population. From 33M in 1990 to 46M just before the dam started construction, to more than 53M today.

That’s like adding the entire country of Australia to Colombia over just a few decades. Unsurprisingly, the country’s power grid was struggling to keep up.

An enormous dam like Ituango could prevent future shortages, blackouts, or reliance on expensive thermal plants.

There’s a reason why Colombia is so eager on dam power.

Hydropower already supplied most of the country’s electricity and it remains one of the cheapest sources of energy in the region.

Above: This was on of the largest infrastructure projects in the country's history.

Unfortunately, many of Colombia’s other hydro projects date from the 1970s or 90s at the latest.

They needed newer, more efficient, higher-capacity hydroelectric facilities so they could scale back and eventually retire these older plants.

Taming the river

Colombia is also home to some of the world’s mightiest rivers that while providing agricultural abundance can also be unpredictable. Aside from providing power, the dam would also tame the Cauca River.

The Cauca River is Colombia’s second-largest after the Magdalena. It slithers through the Andes for 965 km, flowing through major cities before finally joining the Magdalena near Magangué.

Indigenous groups and Afro-Colombian communities depend on it for fishing and transport, while the river valley houses millions of Colombians, making it one of the most densely populated Andean corridors.

But it also plays another, vital role. It supports the Valle del Cauca, which is one of Colombia’s largest and most productive agricultural regions.

The Cauca River supports Colombia’s sugarcane industry, with more than 200,000 hectares of sugarcane crops. Over 90% of Colombia’s sugar and 100% of its ethanol fuel blends come from the Cauca Valley - and its irrigation systems draw directly from the river.

Higher up in the basin, especially here in the Eje Cafetero, the Cauca’s tributaries sustain another famous Colombian export. Coffee.

Altogether this one river sustains one of the richest farming regions in Latin America and supports food security for millions. But where the river gives, it can also take away. The Cauca River has historically caused crop destruction, livestock loss, soil erosion and infrastructure damage thanks to seasonal flooding.

Columbia’s mighty new dam could act like a buffer, evening out the extremes of the Cauca River. Hidroituango’s reservoir provides flood-control capacity, which can lower peak flows during rainy seasons, protect riverbank communities and their fields, and reduce recovery costs after major floods.

From every angle, this was supposed to be a win.

An impossible location

And so construction began in 2010. Immediately, the location of the dam in the Central Andes proved incredibly difficult. Not just geographically. Politically, the region surrounding Hidroituango has been, well, violent. That’s thanks to Colombia’s other famous export.

As a result, the dam’s reservoir is thought to cover dozens of mass graves.

Above: Building the dam was supposed to be a sign of peace.

Experts estimate that there were 3,500 murders, 600 forced disappearances, and 110,000 displacements in the region between 1990 and 2016 alone.

Financed with public money, Hidroituango was marketed by the government as a step forward from that violence. A development project that was supposed to bring peace and prosperity to a place that had never known it.

Just to get to the site workers had to build roads on cliff-like slopes. Huge pieces of construction equipment had to be carried around narrow mountain passes.

Building a megadam

The first step of building any dam is - say it with us now - diverting the river. If you’ve watched enough B1M videos you should know that ordinarily the river is diverted through temporary cofferdams or channels, leaving the site dry for construction.

This is as true as it is for the largest dams in the world as it is for the highest or the very smallest The canyon walls for the site were deep. Engineers had only a single option. They had to dig tunnels through the mountains.

And then, in 2012, while the main construction of the diversion tunnels was just beginning, the project was mired in controversy thanks to a nefarious bidding process, alleged corruption and delay after delay. Despite this, work on the tunnels began.

Now if you’ve watched enough of our videos you know this is when we usually start talking about TBMs, AKA tunnel boring machines. But there is no way that kind of machine would fit here. So the tunnels were dug the old fashioned way. With explosives.

The Ituango tunnels were excavated mostly with a drill-and-blast technique. First, rigs drilled multiple holes into the rock face.

Then the holes were filled with controlled charges, and explosives were detonated in a timed sequence to fracture the rock.

The rock was then removed by loaders and trucks, and shotcrete - also known as sprayed concrete - as well as rock bolts, steel ribs, and mesh were added to stabilize the cavity.

Above: The site was incredibly difficult.

These deep tunnel works required constant ventilation, drainage, and monitoring to prevent collapses because this is the Central Andes. Which is one of the most geologically active regions in the world. Landslides and earthquakes are pretty much par for the course.

By 2014, four years after construction started, the tunnels were complete, and the river could finally be diverted.

Rushed construction

Now… this is important, because it’s what led to the disaster that came four years later in 2018.

Empresas Públicas de Medellín, or EPM is the state-owned utilities company in Colombia that designed and built the dam.

By 2015, the project was very much behind schedule. In fact, the entire project was supposed to be completed the year before. So, EPM signed a USD$100,000 contract to speed up construction.

Construction ran 24/7 and managed to recover 18 months of delays. But shortcuts were taken.

EPM had an array of financial incentives to keep production on schedule. They were set to receive USD $22.3M if the project began to deliver energy as promised before December. The company had already reported the revenue from the dam in its financial budget, and thus would have begun to lose credit standing if the profits weren’t realised.

By 2017 the dam was 70% complete. And by the 13th of May 2018 the entire project was just weeks away from being finished. This is when one of the dam’s diversion tunnels collapsed.

Disaster strikes

Authorities ordered the evacuation of more than 25,000 people downstream, fearing the dam could burst.

So how did this happen?

The diversion tunnels were excavated through highly fractured rock in the steep Andes -engineers expected difficult ground, but the reality was even more unstable. Tunnels crossed through fault lines and crushed rock, which are prone to sudden deformation. Groundwater had softened the rock, meaning it couldn’t hold as much weight as it should have.

The quality of the rocks varied greatly over just a few metres, from strong to crumbly, making long-term stability hard to predict.

There was just a lot more of the Cauca River running through the system because it was no longer the dry season. It was a particularly nasty wet one.

One small problem could easily escalate. Even a small deformation in the tunnel lining could cause cracking, allow water intrusion, or create larger structural damage.

And that is exactly what happened.

Above: The spillways overflowed and threatened the dam.

A deformation in one of the diversion tunnels created a blockage, a backup of huge water pressure behind the obstruction. With nowhere for the river to go, the tunnel effectively became a pressurized cavity, and collapsed.

Once the tunnel collapsed the river lost its primary diversion route, overwhelming the other two tunnels. Within days all diversion tunnels were destabilized or had collapsed. They lost control of the river.

In response to this engineers had to rapidly increase the height of the dam in a matter of weeks. They continued their 24/7 construction schedule with dump trucks and loaders, this time motivated not by money, but by fear of the dam’s eventual failure.

The wall was raised to 225 metres, high enough to contain the rising water.

They then had to open and use the spillway - which had not been used or even tested yet.

Once opened, the spillway provided a controlled outlet for the Cauca River, restoring partial stability.

But it was far from over.

Among the downstream consequences were the unplanned flooding of the machine house, structural damage to intake components, and months of interrupted construction.

A Dutch underwater construction specialist was tasked with the underwater isolation of the dam’s intake structures.

They made custom-designed mechanical plugs, which allowed divers to seal off and dewater entire sections of the dam.

New diversion tunnels were built, many of the old ones abandoned. Presently, there are still four more turbines to bring online, once those are installed the dam will be nearly complete. Full completion is now due to be 2027.

Many lessons have had to be taken away from the Colombia Dam disaster. Mainly that money and political pressure cannot substitute for rigorous engineering practice.

Local communities were not properly consulted either and environmental impact reports failed to take into account the enormous risk and cost to human life the failure of such a project would result in.

While it’s all well and good to reach for the sky with ambitious country-changing megaprojets. You have to remain at least a little grounded to ensure those projects don’t change your country for the worse.

This video and article contain paid promotion for Brilliant.

Additional footage and images: Loren Moss, Noticias TN, Al Jeezera, EPM and El Tiempo.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.