How Disneyland Was Built

- Youtube Views 377,373 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

IN THE SUMMER of 1955, Walt Disney had a problem. He was a few weeks off opening his most audacious venture yet and he had a decision to make: should he install flushing toilets or drinking fountains?

His plumbers had gone on strike and there was not enough time to do both. It was the last thing he needed. He was heavily in debt and had decided to stake not just his reputation but his personal fortune on building an amusement park, something which was normally free to enter.

But he needn’t have worried. By combining technical wizardry with the magic of the big screen, Disney had hit upon perhaps his most consequential innovation yet and one which would transform his dwindling kingdom into a global empire.

At the end of WWII, Walt Disney was in a bind. His movie studio had made it through the war making propaganda films, but he was now heavily in debt and it was beginning to seem like the glory days of Disney were in the past. But the man behind the world’s most famous mouse wasn’t done yet.

Above: Walt Disney in 1935.

A chance visit to a railroad fair in Chicago in 1948 sparked an interest in fairground rides. Amusement parks and fairs were nothing new at the time, but for Disney they lacked a certain magic. Usually they were designed around rides, with some attention given to scene setting and decoration, but nothing resembling a creative vision.

Disney wanted to create something new. A place with rides and attractions, but more than that, it would tell a story. It would project an image of an idyllic world, one of innocence and wholesomeness, where children could let their imaginations run free.

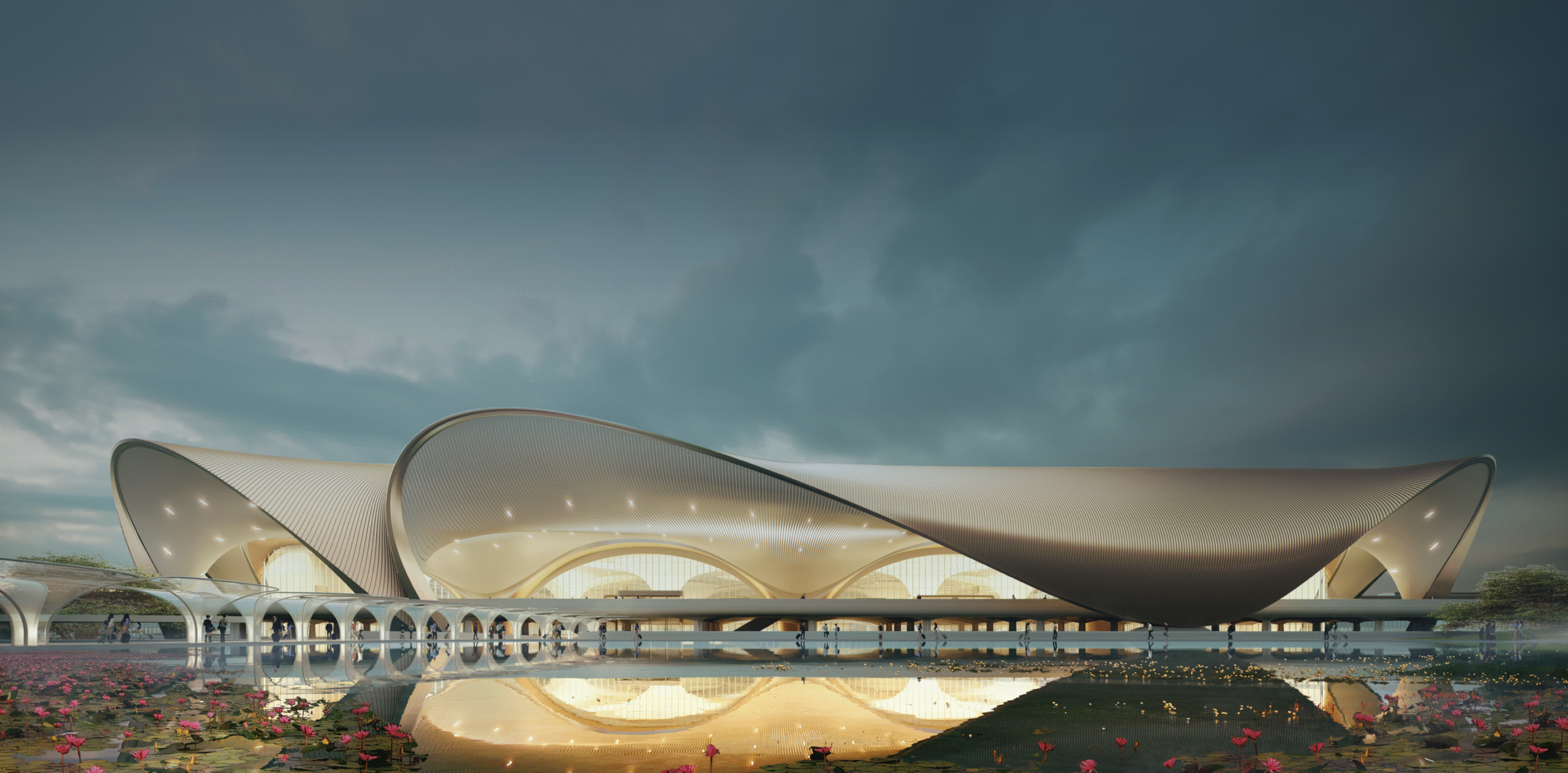

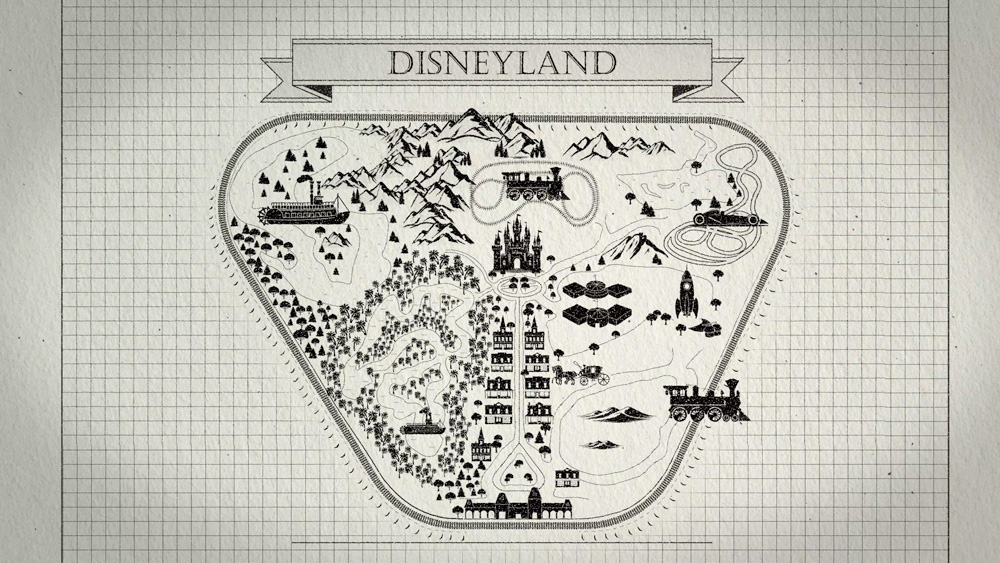

Above: An illustration of the original Disneyland layout.

To get his idea off the ground, Disney called in art director Herb Ryman and over the course of a frantic weekend in September 1953 they developed the initial concept for Disneyland. What they created was something radically different to anything that had come before.

The first major difference came in the layout. While researching other parks, Disney found one of their weaknesses was they often lacked a coherent plan, making them confusing to navigate.

If he were to create the happiest place on earth, it would have to be simple to get around and to do that, Disney had to meticulously design the flow of people as well as the attractions. That began at the entrance.

At the time, amusement parks in the US were typically free to enter and as such had multiple entrances. Disneyland however would have just one. By restricting the access to the park in this way, Disney was able to create a tightly curated experience from the moment guests stepped foot in his park.

Visitors would be greeted by an embankment, on which sat a station for a miniature railway, that ran the perimeter of the park. This would also conceal the park’s first illusion, the embankment doubling up as a physical barrier to prevent the sights and sounds of the outside world getting in.

From there, they would enter the park via a tunnel, which Disney called the “stage curtains”. A small plaque marking the point at which guests left the real world and entered the world of Disney’s imagination.

Above: The plaque welcoming visitors to Disneyland.

First stop after entering was Main Street USA, an idealised version of the American high street, heavily based on Disney’s hometown of Marceline, Missouri. From there, the park would make use of eye-catching visual elements, which Disney would coin as “weenies”, to pull people around the park.

The grandest of these would of course be a fantasy castle, which would draw visitors towards a central plaza: the hub from which every land, ride and attraction would radiate out. As well as making navigation easier, it would create a point at which people could meet and rest.

Branching off from this were a series of themed areas. Other parks had often included novelty buildings to give a sense of the exotic, but these would be standalone features, rather than part of a coherent theme. What Disney planned was total immersion. Just like the park itself, each land would be visually cut off from anything that might spoil the illusion.

Above: Visitors to Disneyland were drawn towards a central plaza which other attractions radiated away from.

With the concept sketches complete, Disney sent his brother Roy off to New York to raise the money for the build. But how do you turn something this new and unique into a reality? Disney had no experience building anything on this scale, let alone anything that broke with so much precedent.

He figured: relying purely on imagination would get him nowhere, but engineering on its own wasn’t entertaining. He needed people who could combine artistic creativity and practical skills to create something unique. What he needed was an imagineer.

Fortunately, Hollywood was full of them. He turned to set designers and artists in his own company, but also from a powerful rival. 20th Century Fox had a backlot four times the size of Disneyland and was filled with scenic artists used to building everything from city streets to steamboats. It was from here that Disney filled the ranks of his new army of imagineers.

The design process started with a pitch, which was then worked up into storyboards and further on into models of increasing sizes. The whole process was fluid, with constant revisions and alterations made throughout, including on some of the park’s biggest structures.

Above: Neuschwanstein Castle, in southern Germany.

Neuschwanstein Castle, in southern Germany was used as the inspiration for the iconic Sleeping Beauty Castle, which lies at the head of the park. It has a gatehouse, turrets and palace, all of which provided the reference for Disney’s version.

On the front of the palace, it also has a balcony, which leads from the spectacular Singer’s Hall. This detail was initially included in the plans but in a sign of how fluid the development was, it was changed purely by chance.

During the design phase, imagineers had taken the model apart for cleaning, only to quickly reassemble it when Walt Disney came to visit. In the rush, they put the palace back on the wrong way round. Disney noticed the mistake but preferred the way it looked and ordered it to be built as the model stood. The balcony still lives on today, but on the back of the castle.

This level of improvisation didn’t stop at the design stage. The Jungle Cruise has become one of the most popular rides of Disneyland and has since been replicated at other Disney parks. Designing a ride like this today requires months of planning and design work by huge teams of people.

Back in 1954 though, the ride’s layout was solely down to one man, legendary art director Harper Goff. With a bulldozer driver looking on, Goff took a stick and walked around the ride’s plot, drawing a line in the soil. Once completed, he drew a parallel line a few metres away.

The bulldozer followed, piling up the excavated soil on the embankments and the layout of the Jungle Cruise was complete.

Now this might all sound a bit “free jazz” but there was a lot at stake. If Disney didn’t pull this off, he stood to lose everything. As Disney’s ambitions for the park grew, so did the bill to pay for it all. By the time construction began, he had taken out USD$17M in loans: over USD$600M today.

He’d even put his own personal fortune on the line, selling properties and cashing in his life insurance to raise funds.

Above: The entrance to Disneyland.

In 1954, he had financing in place but with such a huge amount of money at stake, he needed the park to start earning as soon as possible. And that meant, opening in time for the lucrative vacation season the following summer.

On 16 July, 1954, a year and a day before the grand opening, Disneyland broke ground. To supplement his crack squad of imagineers, Disney brought in two crucial figures to oversee the constriction: Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood and Joe Fowler.

Wood was a savvy businessman with a keen eye for organisation. It was he who had found the site Disneyland was to be built on: 160 acres of orange and walnut groves in Anaheim, California. At the time Anaheim was a rural farming town, but its flat land was perfect for building on and and access to the recently completed freeway meant downtown Los Angeles was just 30 minutes away.

Wood had previously worked at General Dynamics, training teams of people to build aeroplanes and soon set about organising the thousands of daily people on site.

Fowler, meanwhile, was a retired admiral and veteran of both world wars. He had spent the last few decades overseeing the construction of warships for the navy. Initially, he’d been drafted in to oversee the construction of the Mark Twain steamboat. But his ability to wrangle logistics made him invaluable for the wider construction effort of the park.

Fowler’s initial assessment of the plans were bleak. Of the 20 attractions planned to be ready for opening day, only six were likely to be ready, 11 were doubtful and three would definitely not be ready.

Together, Fowler and Wood adopted a strategy that prioritised the important storytelling aspects of the park while finding ways to cut corners and find efficiencies elsewhere. Their aim wasn’t perfection, instead they raced to get everything “good enough for opening day”, with a view to continue work afterwards.

But among the cost saving and improvisation were some truly impressive innovations. Main Street USA is designed to welcome visitors into a quaint, wholesome vision of Americana.

But it doesn’t take long to spot the movie magic at work here. Only the ground floor of each building is occupied, because the upper floors are too small. That’s because this whole street uses forced perspective.

Above: Main Street USA in Disneyland.

The technique has long been used in Hollywood, where sets are built at distorted angles to create the illusion of depth, or height in a studio.

Building a lifesize American high street was beyond even Disney’s means, but shrinking everything would just make the street look small. Instead, the buildings were constructed to a range of sizes, with ground floors built at a near 1:1 scale and the first and second floors built at increasingly smaller scales.

By decreasing the height of the building the higher it gets, our eyes are tricked into thinking they are further away and we assume it's taller than it is.

The most effective use of forced perspective however, is on the iconic sleeping beauty castle. The tallest tip of the castle rises 23-metres off the ground making it slightly taller than the White House. So big, but not a towering fortress.

To make it appear bigger, like Main Street, each storey is built at a slightly smaller scale. But that effect is enhanced by introducing so many disconnected elements, all of a different height. Because there are no consistent storeys, our brain has less of a reference for how tall it should be, making the castle appear taller.

On July 17, 1955, after a year of frantic construction the moment of truth had arrived: the opening day of Disneyland. Everything had been building up to this moment. Thousands of guests were invited and a live TV broadcast was scheduled. But the opening was blighted by a series of disasters.

The park was swamped with people after thousands of counterfeit tickets were sold. Just as Joe Fowler had predicted, many of the rides weren’t finished and most of those that were ended up breaking down.

Above: Sleeping Beauty Castle.

A gas leak near the Sleeping Beauty Castle nearly burned it to the ground and the Mark Twain almost sank with the amount of people boarding it.

As for the striking plumbers: Walt had opted to finish the toilets on time, rather than drinking fountains, leading people to accuse him of a cynical ploy to buy drinks instead of providing free water.

But ultimately, none of that mattered. Just as his first cartoons had done nearly 30 years earlier, Disneyland had captured the public imagination. Work on the park went on and over the following years rides were continuously improved. Despite the princely entrance fee of USD $1 for adults and USD¢50 for children, within two months of opening, 1 million people had visited the park.

Disneyland had become so iconic, on a trip to America in 1959, President of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, publicly expressed his and his wife’s disappointment that they were barred from visiting.

For his part, Disney was never completely satisfied with Disneyland and with the lessons he had learned, quickly turned his attention to building a bigger, better version of his park in Florida. Walt Disney died before he could ever see the completion of his next creation, but Disneyworld would prove to be one of the biggest and most sophisticated theme parks ever built.

70 years on, the rough edges of opening day are long forgotten. What endures is the blueprint Walt created: a place built with the tools of Hollywood, the discipline of engineering and an imagination all of his own. Disneyland didn’t just revive his studio, it rewrote the playbook for how we design experiences, cities and entire worlds.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Disney, Orange County Archives, City of Anaheim Public Library, Library of Congress, ABC.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.