Why Canada is Digging a Huge Pit Under Its Parliament

- Youtube Views 1,906,947 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

IT'S July 30th, 2020, and workers have started digging a huge hole, right outside parliament, in the Canadian capital.

Well, when we say ‘digging’ we actually mean blowing it up with explosives.

That date marked the launch of an extraordinary construction project now taking place underneath the most important building in the entire country.

Another blast quickly followed, then another, and three years later the result was a gigantic pit with Canada’s answer to Big Ben looming over the precipice.

Why is this happening? Because the future of the nation’s most prized asset is on the line — a building that has overseen the last century of its growth.

And this mammoth excavation has only just begun.

Background to the build

If we asked you to name the top three Canadian cities, what would you go for? Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver probably. They do have the biggest populations by metropolitan area.

Don’t forget Ottawa, though. After all, it is the capital city and has been since the country was founded in the 1800s.

Above: A map of Ottawa, where the English and French-speaking regions of Canada meet.

Queen Victoria chose it for its position near the border of Ontario and Quebec. And because it was surrounded by forests, meaning it could be defended more easily in case of any aggression from the United States.

To cement their newfound federal status, Canada needed somewhere to house their parliament.

They decided to put it on a hill overlooking the Ottawa River. It would consist of three separate buildings — or Blocks — arranged around a large lawn with the biggest in the middle.

This ‘Centre Block’ was to be the home of the House of Commons and the Senate Chambers, along with offices for MPs, ceremonial spaces and a library.

Up in flames

Construction began in 1859 and was finished 17 years later. Sadly, however, it was to have a relatively short life.

In 1916, the building burnt down in a huge fire — the true cause of which remains a mystery. Only the Library of Parliament survived.

A new Centre Block was quickly commissioned, finished in 1927, and this one lasted a lot longer — in fact, it’s still standing today.

Like the original, it was built in the Gothic Revival style, with gargoyles, grotesques and friezes adorning the exterior.

But it wasn’t just a simple replica. The giant Peace Tower was built to commemorate those who died in the First World War, and is 70% taller than its predecessor.

Above: Centre Block pre-renovation. With 53 bells inside it, the Peace Tower is just a few metres shorter than London’s Big Ben.

And yet, while the building might have remained intact, over the last century it has deteriorated.

When surveyors inspected the iconic building, they found eroded concrete supports, water infiltration in several areas and some of the structural steel was beginning to rust and break down.

It’s also now seen as vulnerable to threats that must not have been seen as a big problem back in the ‘20s.

The structure has no earthquake protection, and before you ask, yes, Canada does get those. They’re usually small, but there have been a few over magnitude 7 in the past.

Another one of those anywhere near Ottawa could be catastrophic for a building like this, made from more than 24 types of stone.

Then there’s the fact it lacks the sort of ultra-high security you would expect from a site of this importance.

And despite attracting more than three million tourists to Parliament Hill every year, there isn’t a great deal for them to do or see, and it can get overcrowded.

Time for a change

Which is why the Centre Block is now midway through a $5BN upgrade that will not just see it fully renovated but structurally reinforced.

Delivered by Public Services and Procurement Canada, it’s the largest and most complex project of its kind in the country’s history.

Above: Signs of damage could be seen all over the building. Image courtesy of Public Services and Procurement Canada.

You only need to gaze across that front lawn to see the scale of what’s happening, because half of it is gone.

In its place, for the time being, is a 23-metre-deep pit stretching across the entire length of the building.

To make it, explosives were used to cut through the bedrock, with 40,000 truckloads needed to carry the material away. Blasting began in 2020 and didn’t complete until 2023.

As for what this is all for, it’s to create room for a massive underground Welcome Centre. More on that in a bit.

A solid start

By the start of 2025, concrete was being poured for the parts of the new centre that have to go in first, such as walls, stairs and elevator shafts.

But the most complicated part of the excavation work is yet to come. This Welcome Centre has to extend underneath the main building, which currently has no basement levels at all. So, they’ve decided to add some in now, 100 years after the building was first constructed.

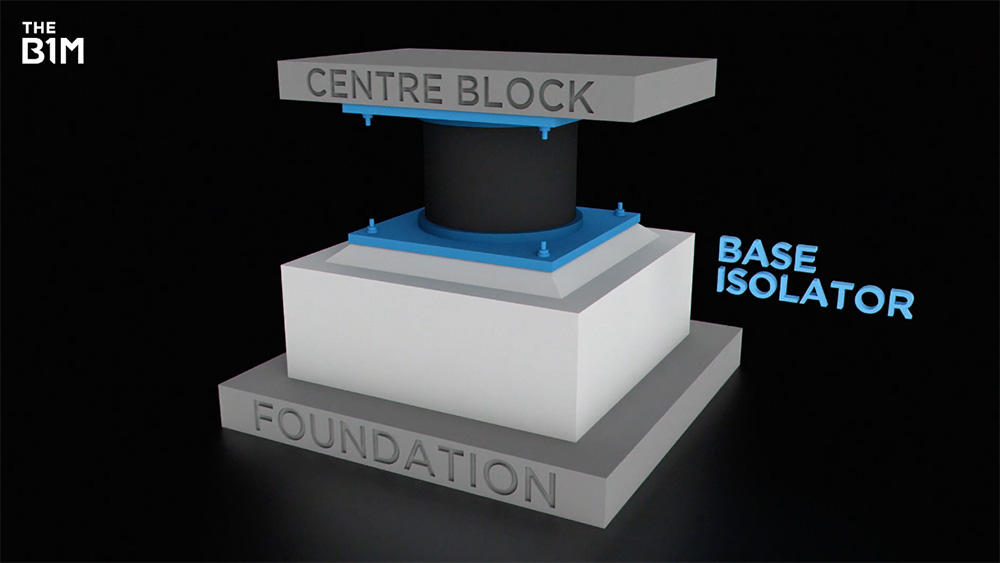

At the same time, a base isolation system will be installed to give the building earthquake protection. To do this, the entire Centre Block must be separated from its foundation.

Understandably, this is not simple. Before any more excavation is done, the Centre Block must be fully supported.

Above: Base isolators like this will have to be installed throughout the complex.

What they’re doing, then, is placing it all on temporary posts before the building is put on top of a new structural grid of steel and reinforced concrete.

Around 800 piles are being driven into the ground, which will be grouped together with steel bracing to create columns.

Workers will then excavate downwards in between these columns and after that the basement levels will begin to rise from the bottom up.

Then it’s time for those base isolators — more than 500 of them. These will sit in between the bottom of the building and the new foundation. Their job is to act as giant shock absorbers in an earthquake.

Although base isolators are not new — we’ve seen them fitted under nuclear fusion reactors and huge telescopes — this is the first time they’ve been installed in this way.

Reaching new heights

It’s an enormous engineering feat, but it’s far from the only big challenge that workers on this site are having to face.

Specialists were called in to secure the four pinnacles around the top of the Peace Tower while they awaited repair.

They did this by running large straps from the base of the flagpole and wrapping them around each pinnacle to hold them steady. And that meant abseiling across the clock faces.

Above: A worker hovers next to one of the pinnacles. Image courtesy of Public Services and Procurement Canada.

While those brave fellas were hanging out at the top of the tower they also fitted monitors, used to measure vibration levels during construction.

Around 500 of these have been placed over the whole site, because a rehabilitation project that ends up doing more damage than it fixes would be … not great.

Meanwhile, further below, another team is having to restore the stones that make up the exterior — all 365,000 of them.

If you thought cleaning your patio was time-consuming then this is a whole other level, but fortunately they have more than just a pressure washer at their disposal.

Lasers. Yes, really. These guys are armed with tools that use focused high-energy light to vaporise surface deposits, clearing away dirt while leaving the stonework unscathed.

Down to a fine art

Inside Centre Block, the building has been stripped right back to its structural elements, while efforts to restore and preserve over 20,000 heritage assets are underway.

50 rooms are being refurbished — some containing unique and irreplaceable works of art — and around 250 stained glass windows are getting a much-needed touch-up as well.

Then there’s the Decorative Arts team, who have been making their way across the building from East to West.

They’re examining the hundreds of sculptures that can be found almost everywhere you look, repairing any that have been harmed by years of erosion and weathering.

.jpg?updated=1760365155700)

Above: A sculptor restores one of the main pieces of stonework that needed attention. Image courtesy of Public Services and Procurement Canada.

So, there’s an incredible amount of work being done here, from heavy drilling and reinforcement down to the most detailed artistry.

But you might be wondering where all the people who are usually here have got to. In other words, the MPs, senators and other high-ranking individuals who tend to wear suits instead of hi-vis jackets.

They’ve had to move out — for now. While this is all going on, the House of Commons has relocated to the West Block, and the Senate is working out of the … well, the Senate of Canada Building. Makes sense.

And there’s a while to go yet until they can return — this project is set for completion in 2031, and the Centre Block won’t fully reopen for another year after that.

Warm welcome

When Mark Carney and his comrades are finally let back in, they — and the public — will be able to admire that stunning new Welcome Centre in all its glory.

Visitors and parliamentarians will enter under a new raised pathway outside the main building.

After passing through a secure screening area they’ll come to the Main Hall, with the foundation of the Peace Tower forming part of the design.

They’ll be able to see the top of it, too — through the skylights that cover the new space, filling the hall with light.

With connections to the West and East Blocks, the centre will act as a secure, accessible front door to Parliament.

Above: A cutaway graphic showing the new subterranean levels. Image courtesy of Public Services and Procurement Canada.

As for the Centre Block itself, Canadians will be handed back a treasure that has been both restored and fully modernised, ready for another century of service.

It’s obvious why historic buildings need to be maintained, but it’s not often you see a restoration project go to such lengths as what’s currently taking shape in Ottawa.

This isn’t just about patching up a crumbling icon; it’s a chance to ensure it can withstand whatever the future holds.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Public Services and Procurement Canada, Braeson Holland, CBC News, CENTRUS, ESO, Library and Archives Canada, National Post, Parliament of Canada, Senate of Canada and Universal.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.