Why a Mormon Mega-Temple is Being Dug-Up

- Youtube Views 384,754 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for Straight Arrow News.

SALT LAKE CITY holds the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest Mormon temple in the world. But it's being dug up…. well, its foundations are, all as part of an estimated $2.4BN project to stop it from falling over.

The temple exemplifies the hidden architecture of one of America’s strangest and most fascinating cities. The plan to keep it standing shows a remarkable u-turn from a city that has normally shrugged off its historic buildings.

A hefty building

The first thing you should know about the Salt Lake City Temple is that it’s very old and very big. It utterly dominates the Salt Lake City skyline - and that’s no accident.

The temple took over 40 years to construct and was finished over 130 years ago.

It was built from granite and quartz monzonite mined from Little Cottonwood Canyon.

It features walls up to nine feet thick, contains 170 rooms and sits on a site 11.4 acres big.

Above: The Temple towering over Salt Lake City.

But while it was built for many things, including weddings and ordinances, it was not built to withstand earthquakes.

And this is actually a big problem.

The Wasatch Fault runs right along the Salt Lake Valley, and geologists estimate a major earthquake - that is one at about a magnitude 7 - happens once a millenia.

That may sound like a lot of time, but the reality is there is a 57% probability of at least one earthquake of magnitude 6 or greater in the next 50 years.

To give you an idea of how devastating that could be, it would be the same size as the 1994 LA earthquake that forever changed building codes in the US.

Or the 2003 Iran earthquake that killed 26,000 people.

Aside from massive quakes there are still plenty of larger ones - magnitude 4 and above - that happen about 4 to 5 times a year within 300 kilometres of Salt Lake City.

A 6.0 quake would likely cause significant damage to the Temple and would require a multi-month, or longer, recovery, as well as a serious stabilization effort.

We don’t have to imagine especially hard when thinking about the damage that would be done to this building. We can look to New Zealand.

On 22 February 2011, Christchurch was struck by a magnitude 6.3 quake. The iconic Christchurch Cathedral was structurally damaged: its spire and upper tower collapsed, while the rest of the building was marked as unsafe.

Because of extensive structural risks, authorities decided the cathedral needed deconstruction and either partial or full demolition.

Heritage groups pushed back against demolition, arguing that the cathedral could be saved rather than torn down. The church was then rebuilt and seismically strengthened.

Future-proof

In many ways, the Church of Latter-day Saints is doing exactly this before disaster strikes.

To make it safer in a large earthquake, they’re “decoupling” the structure from any ground motion. This is what base-isolation is.

It allows the building above to move independently - or semi-independently - from the ground below, reducing the forces that the building itself feels during a quake.

The system is designed to allow up to 1.5 metres of horizontal movement in any direction during a strong quake.

Above: The complicated engineering holding the Temple up.

This would protect the building’s ornate stonework and masonry, as well its historic interior… and any people that would happen to be inside.

Here’s how they’re actually building the system.

They excavated around the temple’s original foundations, down to about 10.6 metres, to create a new lower level where the isolators will sit.

To support the structure while they dig, they used underpinning techniques: micropiles, secant piles, tie-back anchors, tensioned tie-rods, hand-constructed underpinning piers, plus consolidation grouting.

This underpinning is critical so that when they remove or modify original footings, the heavy stone walls don’t shift or settle dangerously.

Once the excavation was done, they built a new concrete foundation that was designed specifically to handle quakes.

This includes transfer beams and girders made from reinforced concrete that go around the temple’s perimeter as well as internally to distribute the immense weight of the church.

They ran lots and lots of post-tensioned cables through the foundation - more than 423 kilometres of them.

These cables physically tie the temple structure into the new foundation in a way that helps control how load transfers, especially during motion.

The old stone footings, and the temple’s existing weight, will bear down through this new system.

The old footings on top, transfer beams, isolators underneath, then the new footings.

All in all they’re installing 98 base isolators under the temple. Each isolator is immense, weighing about 8,000 kilos. The isolators are essentially “bearings” between the new concrete footing and the transfer structure.

During an earthquake they slide and move so that the temple doesn’t take the brunt of it. Try to think of it like a raft made of concrete‐filled steel pipes that are bored under the building.

Once the full weight is transferred to the isolators, they will back-excavate soil directly under the isolators. This is so that in a quake the structure can “float” on them, rather than being constrained by the soil underneath.

The isolator-bearing system is vertically stiff, meaning it resists vertical loads well like wind, but it’s also horizontally flexible. This is exactly what you want for base isolation.

Retrofitting a 19th-century stone building is much harder than building a new one.

They have to be extremely careful not to damage the stonework, or any part of the building.

Above: The Temple under construction.

Because of the complexity, the project is very time-consuming. The church originally hoped to finish by 2025, but more recently has pushed things into 2026.

This is because they’re not just installing isolators, they’re also reinforcing walls, spires, and other architectural elements, because isolation alone doesn’t guarantee zero damage in a worst case scenario.

The renovation includes creating more space for ritual baptisms and increasing seating in instruction rooms. They’re also building a north addition with a sealing wing - which is where Mormon’s get married.

This is a major upgrade to the church, which itself took over 40 years to construct.

This Temple is a declaration

You have to remember, this isn’t simply a church. This building is a declaration. In its time it was radical.

Led by the future first governor of Utah Brigham Young, 148 Mormons came to Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Their goal was to establish a secluded town safe from persecution.

At this time Mormonism was a fairly new and controversial religion, facing intense criticism and backlash from Christians.

In fact, the founder of the church, Joseph Smith, had been murdered just a few years prior.

When they arrived in Utah they found a harsh, isolated landscape. Despite this, Young set about creating his city.

He knew the importance of a symbol and so anchored his plans around what would become an enormous temple.

There were no railways. No quarries. No infrastructure. Work formally began on the Temple in 1853. Crews excavated footings and laid early foundations using sandstone. But almost immediately, the project faced its first major obstacle.

By the late 1850s, the region was on the brink of conflict. With U.S. troops marching toward Utah, workers buried the foundation under dirt to prevent it being destroyed. Construction halted.

It would take years before the site was ready to build again. And when it was, the decision was made to build it out of granite.

The problem? The nearest usable granite was 32 kilometres away in Little Cottonwood Canyon. And it wasn’t exactly easy to move.

With no heavy machinery workers blasted blocks of granite loose, hand-shaped them, and loaded each piece onto a wagon. Ox teams hauled the stones across rough, unfinished terrain. It would take up to four days for a single trip.

Every block had to be shaped with extraordinary precision. This was slow, painstaking work, and the scale was enormous. The walls would be 3 metres thick in places.

The design by architect Truman O. Angell combined Gothic and Romanesque elements, but everything had a symbolic value.

There were stars, suns, the and the now-famous statue of the angel Moroni.

This wasn’t only decorative flourish. It was storytelling. Reminiscent of renaissance churches, or even Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia today. He was using architecture to illustrate God.

Through the 1870s and 1880s, the towers climbed higher. Steam-powered tools eventually arrived, but the work was still intensely manual.

Craftsmen shaped stone by hand. Timber was cut locally. Metalwork was forged in small workshops.

And all the while, the settlement around the temple grew from a remote outpost into a city.

The birth of Salt Lake City

The Temple became the anchor point of Salt Lake City’s urban plan. Streets, public squares, and civic institutions aligned themselves around the temple block.

You see, Salt Lake City isn’t just another American grid city. It’s one of the most deliberately planned urban layouts in the world.

Brigham Young carried out the “Plat of Zion”. Essentially a template for a city that was drafted years earlier. It outlined an ideal urban settlement, a perfect grid of square blocks and wide streets. While other frontier towns evolved messily, Salt Lake City was engineered.

Within days of arriving, surveyors were marking out the first streets, laying down a grid aligned almost perfectly with the cardinal directions, north, south, east and west. At the centre an 11-acre block was reserved for the community’s most important building, the Salt Lake Temple.

Above: The Temple has shaped Salt Lake City around it.

A typical New York City block is about 80 by 200 metres. This was a fairly standard layout for cities of this time.

Now let’s compare it to Salt Lake City’s grid. Their blocks were 200 by 200 metres. The largest of any American city by far.

The streets were incredibly wide too. New York’s were about 18 metres, 30 at the most. Conversely every street in Salt Lake City was more than 40 metres wide. Enough space for a team of oxen to turn around without stopping traffic. We’ll take their word on it.

While this scale was strange for the time, it allowed the city to have a number of quirks. Quirks that turned out to be quite valuable.

Every block measured 10 acres, each divided into just eight enormous lots. They were effectively micro-farms.

This allowed Salt Lake City to function as a hybrid between rural and urban life. Families grew crops on their lots, the streets acted like irrigation channels during droughts, and the huge block size reflected a self-sustaining community model.

They also had other benefits, acting as firebreaks that protected against catastrophic blazes as well as providing straight, unobstructed utility corridors.

In the long run, those large blocks posed challenges for walkability and downtown density, but allowed the city to adapt very easily to the invention of the car.

The past is present

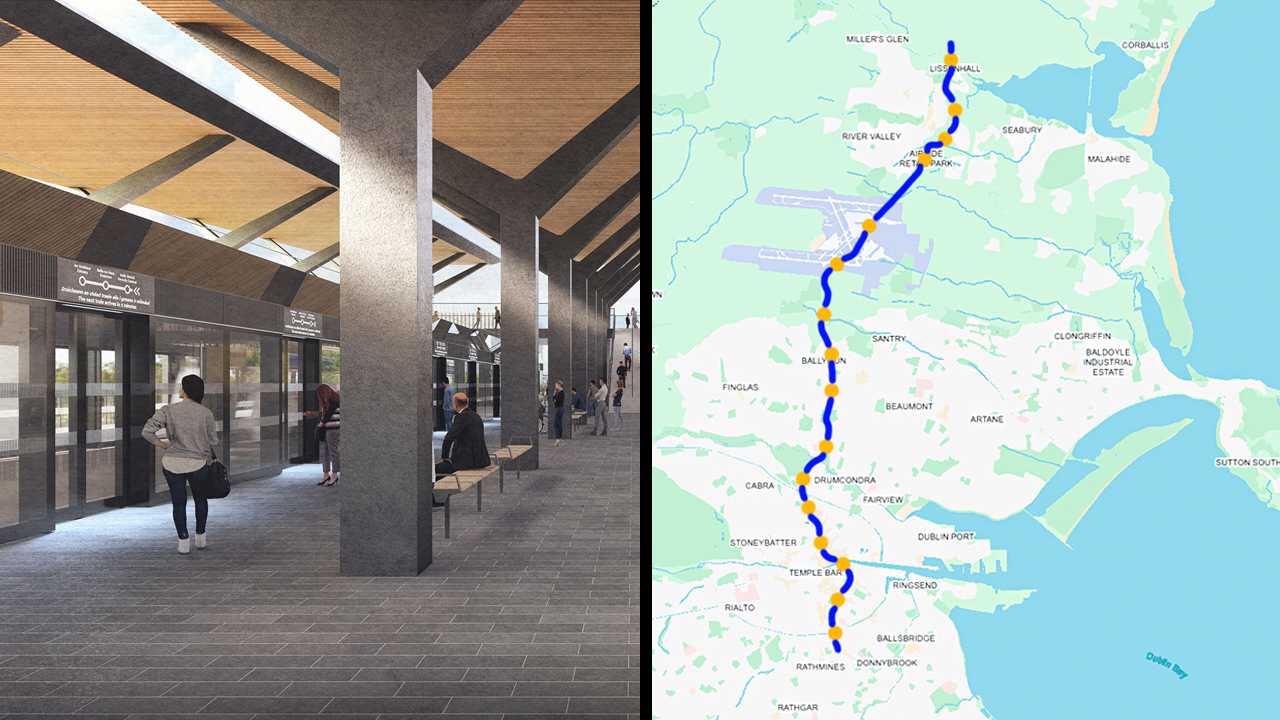

Over the 20th century, Salt Lake City expanded far beyond the original grid. But the city’s basic DNA, wide streets, generous rights-of-way, and steady block organisation, enabled major infrastructure projects, from interstate highways to TRAX light rail.

Salt Lake City has struggled to preserve many of its historic buildings, thanks in part to the city’s success. Skyrocketing land values and pressure from developers has meant the destruction of many heritage buildings.

Spending more than $2BN saving one of the city’s oldest and most iconic buildings will go a long way to showing the rest of the city why preservation is so important.

The hope is this project will have a ripple effect.

Works are due to complete in 2026 with doors to the temple opening in 2027.

Thanks to these engineers this building will go from being in danger of collapse in an earthquake to becoming one of the most seismically resilient historic structures in the world.

That’s well worth the effort.

Additional footage and images:The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Channel 4 News, Daniel Lademan, The Telegram and Christ Church Cathedral Reinstatement Project.

Download the Straight Arrow News app by clicking here https://www.san.com/b1m to stay informed with Unbiased. Straight Facts.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.