Building New York's 21st Century Superscraper

- Youtube Views 1,086,536 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

WITH more supertall skyscrapers currently under construction than were built in the entirety of the previous century, New York City’s skyline is changing like never before.

While the iconic Empire State and Chrysler buildings have dominated Midtown since the 1930s, one of the largest buildings New York has ever known is about to join them on the skyline.

Above: One Vanderbilt is one of the largest buildings ever constructed in New York (image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates).

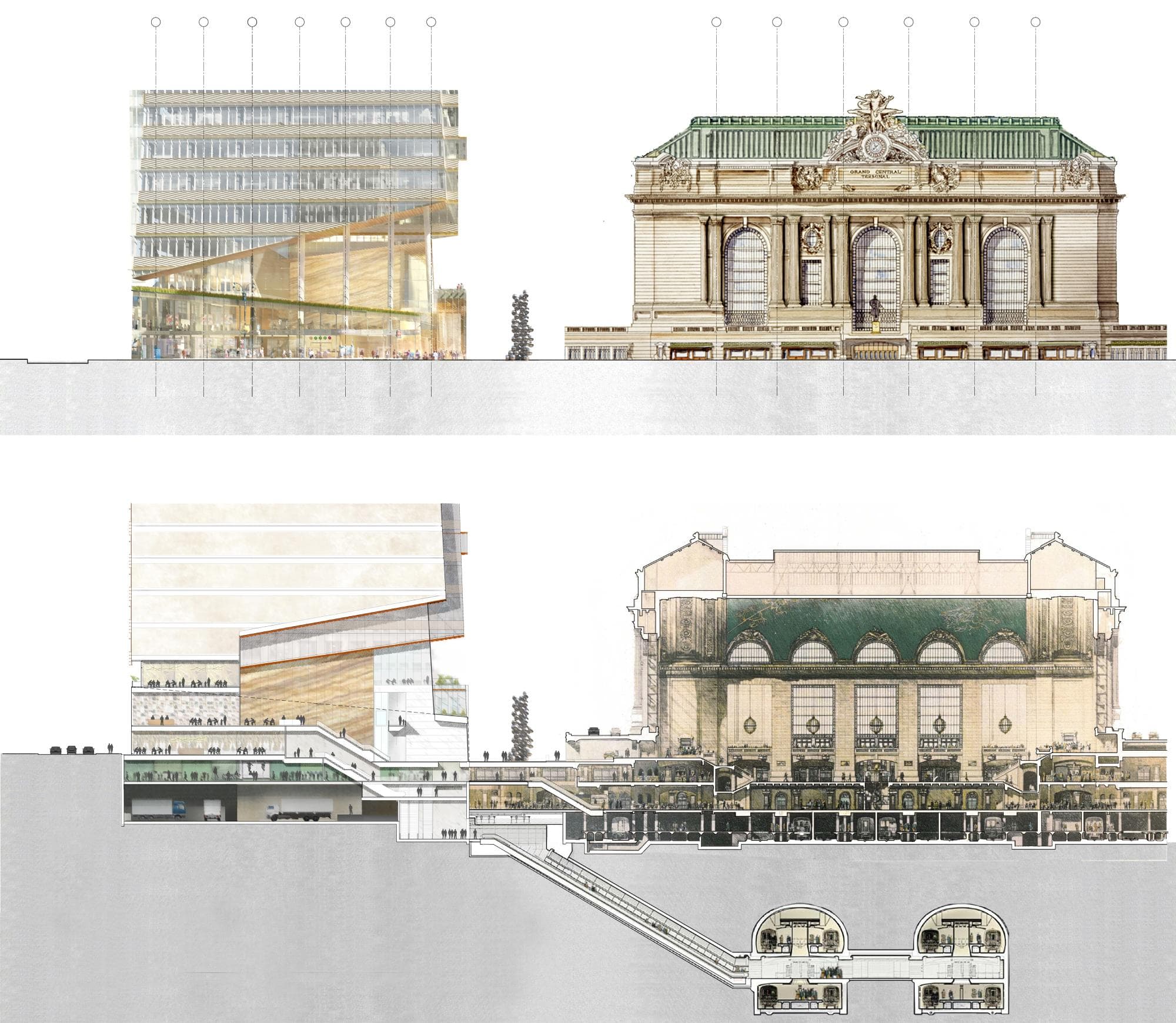

First conceived as far back as the early 2000s, the developers of One Vanderbilt began purchasing buildings adjacent to Grand Central Station with plans to construct a major new office tower on the block bound by Vanderbilt and Madison Avenues and by 42nd and 43rd Streets.

Having been postponed by the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, plans for a commercial skyscraper, 1,300 square metres of redeveloped pedestrian space along Vanderbilt Avenue and substantial improvements to the Grand Central Terminal transit network were first unveiled in 2014.

Designed as a modern take on New York’s famous tapering skyscrapers, One Vanderbilt carefully responds to its surrounding context while respectfully paying homage to the skyline that it joins.

Above: One Vanderbilt adds a modern twist to the iconic skyline it is joining (image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates).

While many of New York City’s historic skyscrapers tapered through setbacks that allowed natural light to reach street level, One Vanderbilt streamlines this concept with tapering sheer walls that rise as four uninterrupted forms culminating in a breath-taking summit.

Rising 427 metres above street level, the tower will stand taller than both the nearby Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, and upon its completion will contain one of the city’s highest outdoor observation decks.

One Vanderbilt achieves its height by purchasing air rights from a number of surrounding properties and effectively stacking them onto its site.

Despite the building's height, the tower will contain just 58 habitable floors - far fewer than other skyscrapers that are comparable in size.

This is due to substantially high storey heights throughout the structure, which range from 4.5 to 6.1 metres, considerably above average.

RISING FROM HERITAGE

Rising directly alongside one of the city’s most historic and well-known landmarks, the base of One Vanderbilt has been carefully designed to improve pedestrian access around Grand Central Station while nodding to the terminal’s heritage.

The new skyscraper’s base is formed from a series of angled cuts that create a visual procession from the tower to the station’s grand facade, while a striking sloping ceiling rises 32 metres above street level, opening sight lines to the terminal.

Above: The tower's base is designed to draw the eye to the historic facade of Grand Central Terminal (image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates).

In addition, the glass and terracotta materials employed across the tower’s facade hark back to those used during the early 1900s when the station was first constructed.

Significantly, New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority required developers to undertake major improvements around Grand Central Terminal, as part of their project.

From pedestrianising Vanderbilt Avenue between 42nd and 43rd streets to improving links between the subway and rail networks and allowing for the construction of the Long Island Rail Road’s East Side Access project, One Vanderbilt’s construction will ultimately enable a further 65,000 commuters to use the station each day.

Above: The construction of One Vanderbilt allowed for significant upgrades to be made to the New York transit system (image courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates).

At a cost of USD $220 million, these improvements are by far the largest private contribution made to New York’s transit system so far.

A NEW TOWER IS BORN

With the demolition of the existing structures on the site commencing in 2015, works to excavate down by 15 metres and remove some 46,000 cubic metres of material began in February 2017.

Constructing a major new skyscraper on a relatively small site in the middle of one of the world’s most densely occupied cities, is far from easy and the challenges of logistics played a key role in how the tower was built.

Conventionally, the multiple concrete pours needed to construct One Vanderbilt’s foundation mat would have taken place over a number of days, causing congestion and disruption in the surrounding area over an extended period of time.

Above: New York City's largest single concrete pour to date was carried out over an 18 hour period (image courtesy of Will Ellis).

To avoid this, the project team coordinated a single continuous pour using four concrete pumps and 420 concrete trucks over a condensed and highly intensive 18 hour period - an activity that the building’s developer claims was the largest concrete pour in New York’s history.

With foundations in place, the tower’s steel frame began to rise, reaching ground level in October 2017 and moving ahead of schedule reached to reach the ninth storey level by February 2018.

Unlike the construction of most skyscrapers, where the concrete core rises ahead of the building’s perimeter structure, One Vanderbilt’s steel frame and floor plates in fact progress first; a common building technique in New York City that has its roots in how different trades used to interact on sites.

However, forming the tower’s core after the steel frame had been erected created further logistical challenges, with the core’s formwork needing to be small enough to navigate through the steel structure to the core’s location.

Above: One Vanderbilt's steel structure rising ahead of the core of the building; a technique common in New York City (image courtesy of Max Touhey)

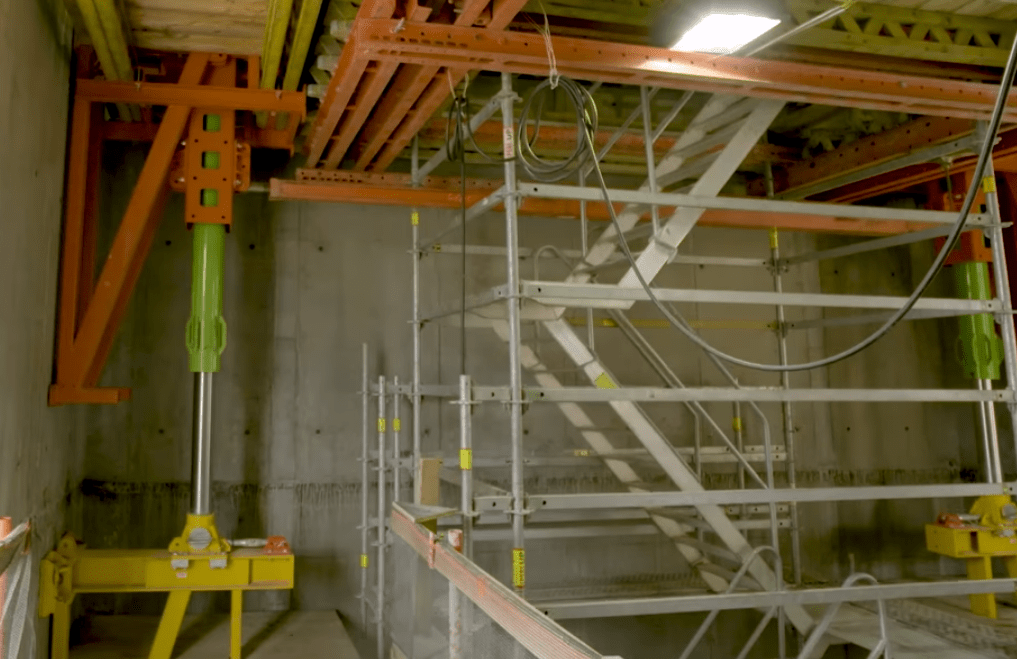

After careful planning, and with approvals in place from city authorities, formwork systems manufacturer PERI delivered One Vanderbilt’s core-forming system under the cover of darkness to avoid disruption.

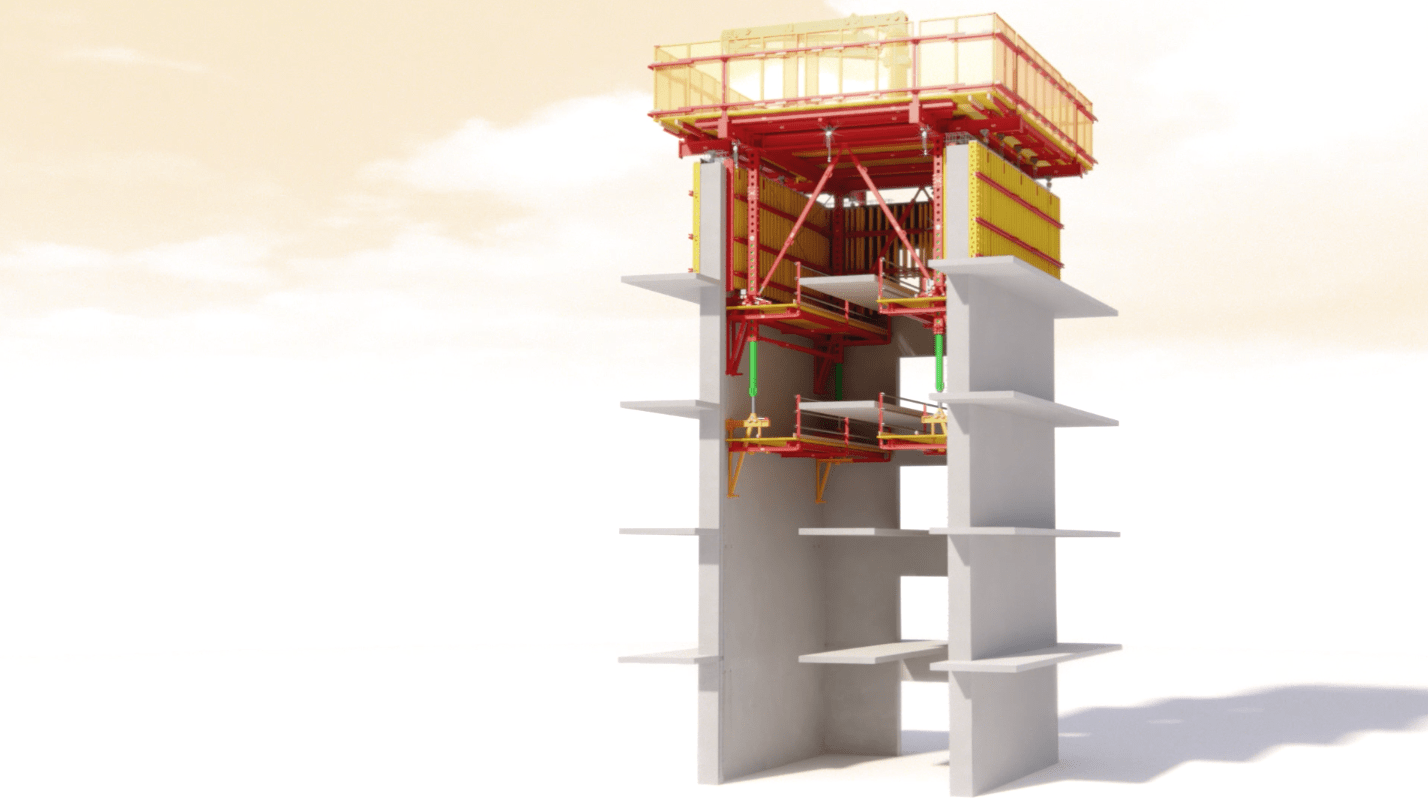

With the initial core walls poured, PERI’s ACS Core 400 formwork system was manoeuvred through One Vanderbilt’s steel frame and installed.

PERI’s system creates a safe environment for those working on the core and has the ability to self-climb the structure as it rises, avoiding the need to schedule time with the project’s cranes which are always in high demand on skyscraper sites.

As each storey of the core is completed, PERI’s innovative climbing sequence transfers the load of the formwork system from the upper working brackets (shown in red in the documentary above), to the lower climbing brackets (shown in yellow).

Hydraulic jacks (shown in green in the documentary) then push the entire system up to the next level.

The red working brackets are secured to embedded anchors in the next pour, and the load of the core system is transferred back to the red brackets. Then, the yellow climbing brackets are released, and the hydraulic jacks bring the lower deck up to join the rest of the core system.

Above and Below: One Vanderbilt's core system self climbs using hydraulics (images courtesy of Peri Formwork Systems).

This sequence is repeated to the very top of the tower.

Once completed, the core system is dismantled and lowered down the structure by cranes, either externally or through empty lift shafts.

The cranes themselves are eventually removed by other cranes or self-disassemble.

One Vanderbilt’s taper means that several elevator and service shafts within the core do not extend the full height of the building. PERI’s system is designed to be easily reconfigured as it rises, reflecting this element of the core design.

THE HEIGHT OF SUSTAINABILITY

Mindful of the environmental impact that urban development can have, developers and engineers have gone to considerable lengths to ensure that One Vanderbilt is at the forefront of sustainability; both in terms of design and construction delivery.

Despite the scheme requiring an extensive amount of demolition works prior to construction, the project team sought to recycle 75% of demolition waste and used an extensive tracking system to identify locally sourced materials, minimising transport emissions.

Above: One Vanderbilt will not only become one of the city's tallest buildings but one of its most sustainable as well (image courtesy of Michael Young).

Additionally, the steel rebar used in the tower consists of 90% recycled content - a significant step up from the standard 60% - and the use of industrial

by-products such as recycled slag and fly ash in One Vanderbilt’s concrete mix helps to further reduce the structure’s impact.

Internally, the tower features a 1.2-megawatt co-gen system that contributes to heating and cooling requirements, while floor to ceiling windows and column-free floor plates maximise natural light, reducing the extent of artificial lighting needed during the day.

The development also features a 22,000-litre rainwater recycling system and ultra-high-efficiency fixtures, reducing the tower’s water consumption by a remarkable 40%.

Above: One Vanderbilt is set to achieve a LEED Gold certification when completed (image courtesy of SL Green Realty).

Together, these systems put the skyscraper on track to achieve both a LEED Gold and WELL certification when it completes in 2020.

At a cost of USD $3 billion and nearly two decades after it was first conceived, One Vanderbilt is now beginning to make its mark on the world’s most famous skyline, a highly impressive scheme that blends heritage with sustainable design and engineering ingenuity to prove this city’s continuing expertise in skyscraper construction.

Learn more about PERI.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Peri Formwork Systems, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, Max Touhey, Michael Young, Jim Henderson, Will Ellis, SL Green Realty, Google Earth, Edward Skira, and Marcos Rivera. Narrated by Fred Mills.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.

Comments

Next up