Why Shanghai Tower Failed

- Youtube Views 7,764,015 VIDEO VIEWS

SOARING 632 metres above the financial heart of China, Shanghai Tower is the second tallest building in the world.

The striking structure features incredibly fast elevators, is home to our planet’s highest observation deck and claims to be the world’s most sustainable megatall skyscraper.

But despite its status as one of modern China’s most iconic mega projects and its ambition to be the crowning symbol of the country’s economic growth, Shanghai Tower has been plagued with challenges.

Above: Shanghai Tower rises 636 metres above the city's financial district.

Plans for Shanghai Tower date back to 1993. When economic reforms were introduced in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the cityscape of Shanghai began to rapidly transform.

To accommodate the demand for office space and to put the city on the world stage as China’s financial capital, a cluster of three eye-catching supertall skyscrapers were planned.

The Jin Mao Building, the first of this trio, was completed in 1999 and was followed nearly a decade later by the Shanghai World Financial Centre.

But Shanghai Tower was always intended to be the jewel in the crown.

Backed by a consortium of state-owned developers and primarily funded by Shanghai’s municipal government, work on the USD $2.4BN tower first commenced

in 2008.

Eight years and 128 storeys later, the twisting structure completed, stunning the world with its scale and unusual form while making the skyscraper super-block one of the densest places on Earth with more than a million square metres of real estate on offer.

Sitting so close together these towers invite comparison. Each one sets a monumental record, only to be dramatically outdone by its successor.

Above: The trio of supertall towers creates one of the world's densest blocks. Image courtesy of Gensler Design.

But since its opening in 2016, Shanghai Tower has faced a myriad of problems - most notably an astonishingly low occupancy rate.

Until as recently as 2018, the building was half empty. The spaces that were leased were let to domestic corporations and only 30 percent of those had actually been able to move in.

The much sought-after multinationals were even more reluctant to sign leases.

There were several reasons for this.

Firstly, bureaucratic red tape and safety concerns from the local fire authorities - who were concerned at the building’s immense height - meant that it took several years for the tower to gain its full fire certifications.

With operating losses soaring, the tower ran more than USD $1.5BN into debt.

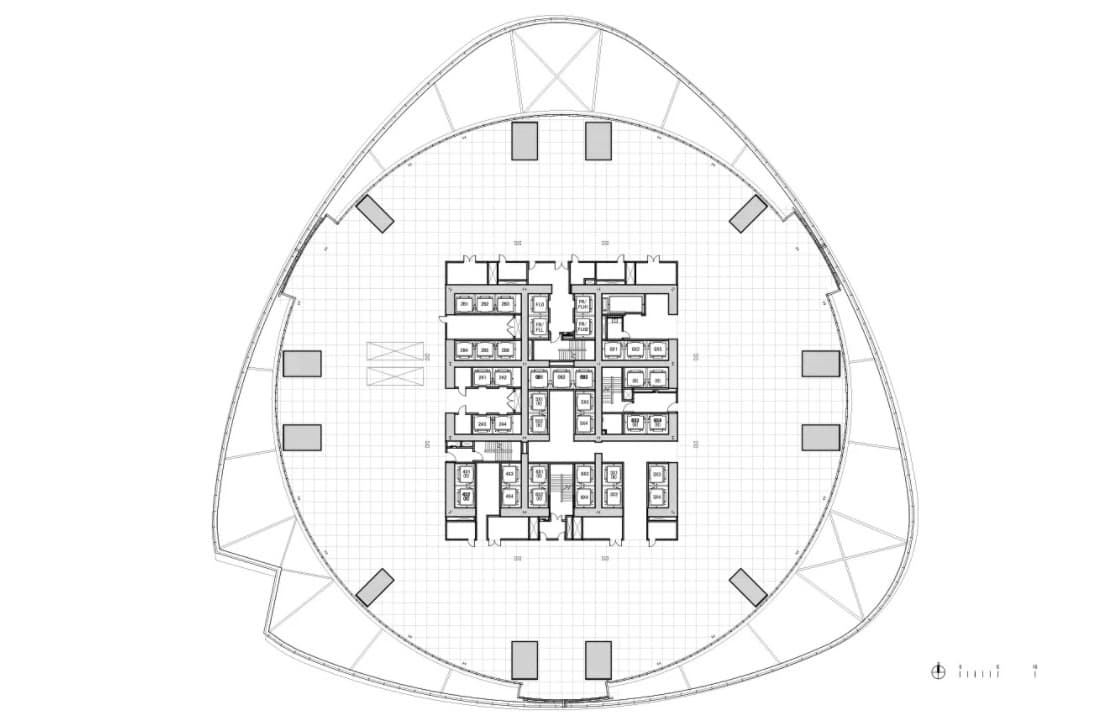

Secondly, the building’s twisting glass facade - ideal for offsetting wind loads - created an impractical floor plate, forcing tenants to pay for large areas of unusable floor space.

Site inspectors found that, on most levels, just 50 percent of the floor space was used efficiently.

Above: The tower's floor plate. Image courtesy of Gensler Design.

The tower’s low occupancy rate is painfully obvious at night, when half the tower fails to light up.

This is partly due to extended delays around the luxury J-Hotel that has been due to open on the tower’s upper floors for many years.

Shanghai Tower’s world-class sustainability credentials - which earned it LEED Platinum certification - were in fact a key part of its commercial strategy.

Investors are always looking for ways to lower the maintenance and energy costs of supertall buildings, while rent for LEED certified structures can be up to 30 percent higher because of their desirable green-status.

As such, the tower boasts over 40 energy-saving techniques - including 200 wind turbines at its summit providing 10 percent of its power, a dual-layered glass skin that naturally cools and ventilates the building interior and a rainwater recycling system.

Above: The tower's low occupancy is revealed at night, when half the structure fails to light up.

But these measures did little to attract tenants in the tower’s early years and in addition to the problems outlined above, Shanghai Tower found itself completing at an unsettling time for the Chinese economy.

With commercial occupancy rates across the city falling, the tower was asking tenants to pay expensive rents when they were looking for bargains.

Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted the lack of competent commercial decision making from China in its construction projects.

No private company in the world would be able to build a tower this wildly expensive and lease so little of it.

Despite pushing the very limits of engineering and being widely praised for its design - that has undoubtedly made it an iconic symbol of China - Shanghai Tower has seemingly fallen short of becoming a monument to the country’s economic success, standing instead as quite the opposite.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Carlos Barria, Adrian Smith, Gensler Design, Shen Zhonghai, Blackstation, Connie Zhou.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.