The Unstoppable Growth of China's High-Speed Rail Network

- Youtube Views 2,605,910 VIDEO VIEWS

TWO-THIRDS of the world’s entire high-speed rail network is now in China.

In the 12 years since its first line opened, the country has dramatically out-built every other nation and now plans to double the size of its high speed network in just the next 15 years.

Travel times have fallen, the country’s economy has boomed, cities have exploded - and the rest of the world has been left wondering how they’ll ever come close to building at such an insatiable pace.

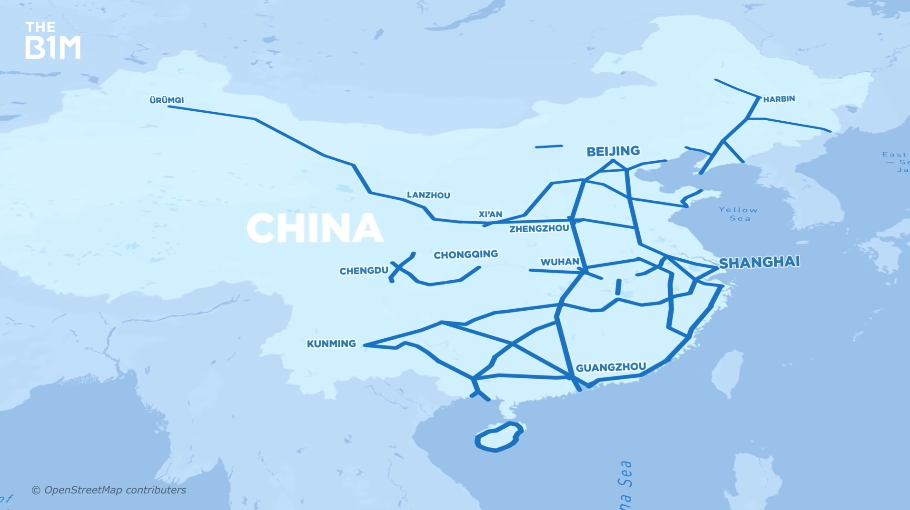

Above: Part of China's sprawling high-speed rail network.

There are high-speed rail networks around the world – but then there’s the network in China.

It’s an insanely large web of track that’s helped ignite an economic powerhouse. In little over a decade, the country has built enough high speed lines to almost circle the globe and the system welcomed 1.7 billion passengers in 2019 alone.

To put that in context, the UK built a high-speed rail line between London and the Channel Tunnel in the 2000s (HS1) that’s equivalent to 0.2% of China’s current network.

The new HS2 line was first proposed in 2009 and Phase 1 of it is due to complete in 2033.

The US has one high-speed line in the north east but it’s arguably not actually high speed and California’s new line won’t open before 2029.

To properly understand how this jaw-dropping network came to be and where it’s headed, you need to look at the story of modern China.

Since the 1980s the country has roughly doubled its GDP every eight years. More than 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty, and between the year 2000 and 2018 over 47 percent of the population has risen to middle-class status.

Cities few had heard of 20 years ago are now vast metropolises. Across the country, skyscrapers soar above your head, factories team with activity and trade booms.

This isn’t all down to high-speed rail. The fast lines have played a huge role in accelerating the country’s growth since 2008, but before that train systems were under pressure.

Faced with buckling infrastructure, state planning for high-speed rail began in 1990 and the first line between Beijing and Tianjin opened in 2008, cutting travel between the two cities from 70 minutes to 30.

Other lines were quickly introduced, linking the cities of Shanghai, Wuhan, Chengdu and more.

Initial trains were imported or built under technology transfer agreements with foreign train-makers, but since then, Chinese engineers have become leaders in the field.

The country now has the world’s longest high-speed rail line, between Beijing and Guangzhou, the world’s fastest high-speed line, between Beijing and Shanghai, and the world’s first commercial maglev line; reaching a top speed of 267mph.

As of 2021, China’s high-speed rail network stretches for 37,900 kilometres, while its entire rail track length runs for over 141,000 kilometres.

By 2035, the high-speed network will have grown to 70,000 kilometres, and the total rail length will extend over 70,000 kilometres.

China’s case for high-speed rail continues to strengthen. The lines it’s built have drastically shortened travel times, improved safety, reduced carbon emissions, and allowed many Chinese people from rural or less developed areas to access to the country’s massive cities.

Studies have also found that tourism increases by around 20 percent in provinces connected to the high-speed network.

The plans for expansion are intended to build on this success but also to address the country’s wealth discrepancy problem.

The rich coastal regions where cities like Beijing and Shanghai are have a far higher nominal per capita income - sometimes more than double or quadruple that of those living in the interior.

Beijing hopes new lines will grow more regional hubs. By 2035, all cities with a population of more than 200,000 people will be connected by rail - and those with more than half a million people will have access to high-speed rail.

The strategy also helps Beijing with its desire to unify the country.

A standard rail line was built from Beijing to Tibet despite its small population, while a high-speed line links the capital directly with Hong Kong; a special administrative region.

In the central government’s own words, the high-speed line to the north western Xinjiang province was partly built to promote “ethnic unity”.

So how has China built such a massive high-speed rail network while other countries have been left standing?

The first reason is demand. The US has eight cities with more five million people, India has seven, Japan has three, the UK just one. China has 14. The Shanghai-Beijing line alone serves more than 300 million people.

This unprecedented rate of urbanisation, combined with rising household incomes creates a need for the fast delivery of people and goods across the country.

At the same time, China’s heavily congested airspace often causes flight delays and high-speed rail is not only cheaper but hugely more reliable.

The high levels of demand allow the Chinese government to make massive investments in high-speed technology and infrastructure.

The sheer scale of the country’s ambition combined with a credible plan to build such a big network and the fact that nearly all of China’s rail is controlled by the state-owned China Railway Corporation means that high volumes of materials can be ordered and produced at once.

The country has also standardised nearly every aspect of construction. Embankments, track, viaducts, electrification, signalling and communication systems are all the same, no matter where you are in the country.

This lowers construction costs, enables offsite manufacturing and cuts build times.

In Europe, high-speed rail costs around USD $25M to $39M per kilometre, while in the US it totals around $56M. In China it’s down at $17M, up to two-thirds lower than other countries.

Of course, there’s a few things that bring the cost of building down. In 2021, more than 40 percent of China’s population - around 600 million people - still live on less than $5 a day and labour costs are low.

Land acquisition is also easier than elsewhere, partly due to the country’s rural geography, political system and culture of obedience toward the state.

The process of moving people out of the way of a new line in the US accounts for around 20 percent of the project cost. In China that’s less than 8 percent.

The country has also kept high speed rail fares low for the average person: tickets are a quarter of the cost of other nations.

Interestingly this often means forgoing making any profit on the lines constructed. Instead China sees the social and wider economic impact of it’s high-speed network as more valuable.

As he took office in February 2021, US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said he’d like to see America lead the world in high-speed rail.

While it may be possible to set the country on a course towards that during his term, the chances of the US overtaking China by building 70,001 kilometres of track in the next two decades feels remote.

Though high-speed rail may seem out of reach to many, the current economic crisis could be an opportunity for countries that keep an eye on history.

In 2008, China responded to the Global Financial Crisis by investing heavily in high-speed infrastructure, stimulating its economy and creating jobs.

Today, that network is the lifeblood of this huge, ambitious, beautiful and complex country.

Narrated by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of Amtrack, Carlos Barria, Billy Shanenunn/CC BY-SA 3.0, 颐园新居/CC BY-SA 3.0, N509FZ/CC BY-SA 3.0, DF4D-0070/CC BY-SA 3.0, and OpenStreetMap Contributors (https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright).

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.