This $15BN Undersea Tunnel Changed Europe Forever

- Youtube Views 1,119,120 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotion for Masterworks

THIRTY years ago one of the greatest engineering marvels of the 20th century was completed against all odds.

The USD $15BN undersea mega-tunnel connected two of the world’s most important cities.

It drew in 1,300 workers, stretched 50 kilometres under the sea, took six years of construction and was centuries in the making.

The monumental project almost broke two countries and many feared it would never be finished.

This is the making of the Channel Tunnel. The seventh wonder of the modern world.

Today the Channel Tunnel is a piece of critical infrastructure many of us take for granted. To get from London to Paris all you have to do is head to St Pancras station, jump on the train, and you’ll be in the heart of Paris in two hours.

That is, if everything’s running smoothly. Despite strikes and recent flooding – this tunnel has served as a trusty link between the UK and France for decades.

It’s not just Paris either. The Channel Tunnel links London to the rail network of the entire continent of Europe. It's made freight travel a breeze too. Moving goods from the UK to Europe has never been easier, but things weren’t always this breezy.

Before the tunnel was built, when crossing from London to Europe meant navigating the choppy and famously unpredictable weather of the English Channel. It took around 6 or 7 hours by rail and then ferry from London to Paris. Now, the journey takes a third of the time.

More than 20M people use the tunnel every year, more than the combined population of London and Paris.

The Channel Tunnel, or Chunnel as it’s affectionately referred to, first opened in 1994 after six long years of construction.

At the time it was the longest undersea tunnel in the world and to this day remains the only physical link between London and Europe.

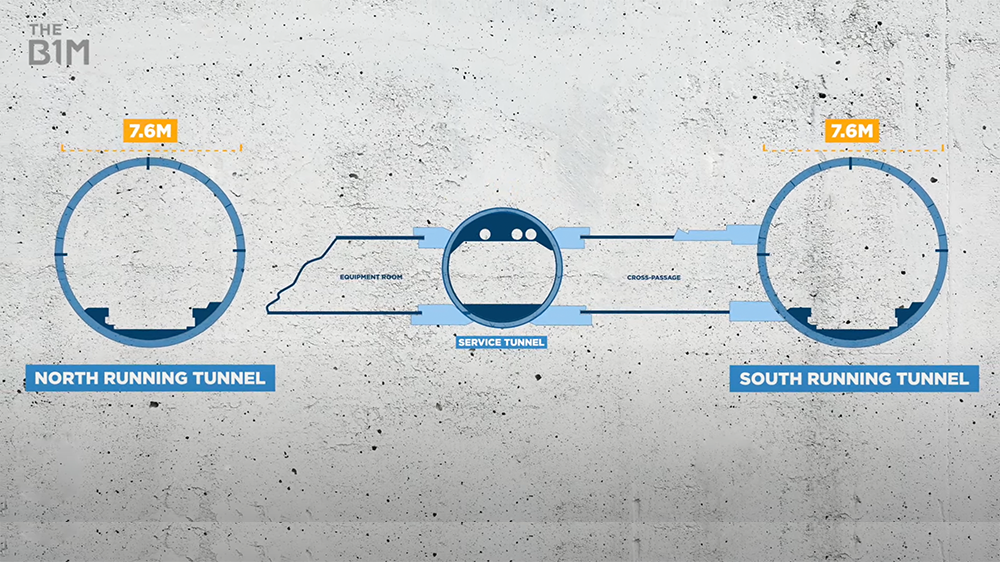

The Channel Tunnel is in fact made up of two main tunnels running parallel to each other and a third smaller service tunnel 4.8 metres wide between them that is used for ventilation and to provide access.

Above: The Channel Tunnel is made up of three tunnels under the English Channel.

The two main tunnels are each 7.6 metres in diameter and spaced 30 metres apart. Both are high enough to comfortably hold a double decker bus.

Every 250 metres are small ducts between the main tunnels. They help dissipate the air pressure in front of the train to relieve aerodynamic drag and help it move faster.

The total length of Chunnel is 50km, of which 38km is located under the seafloor.

The tunnels aren’t actually straight lines but curve up and down and left to right so they can stay within the layer of chalk at the bottom of the channel. At its deepest point the tunnel is 75 metres below sea level.

At its opening in 1994, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the Chunnel as one of the seven Wonders of the Modern World. And when you look at the scale of it it's not hard to see why. No other underwater tunnel had come close to achieving what this one had accomplished.

There had always been a desire to connect the British isles with Europe. No matter how much the UK may think, and sometimes vote against it, Great Britain is intrinsically linked to the continent both economically and socially through trade and the movement of people.

As early as 1802 there were plans for a tunnel. Although back then they only wanted one big enough for horse-drawn carriages to travel.

Many Brits thought this was just a ploy by the French to launch an invasion and the idea wasn’t so popular.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, a series of bridge and tunnel ideas were put forward. And in 1974 British construction workers actually started digging their way to France. But just a year later the UK government called the project off.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that French President Francois Mitterrand and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher began making plans to build what we now know as the Channel Tunnel.

With record unemployment, key industries collapsing, and massive civil unrest, the early 80s were a turbulent time in the UK and neither the British and French governments did not have the funds to build this daunting megaproject, so it would have to be privately funded.

Instead of a series of suspension bridges or causeways, the two governments opted for the plan proposed by the Balfour Beatty Construction Company, which was later taken on by a consortium called Transmanche Link.

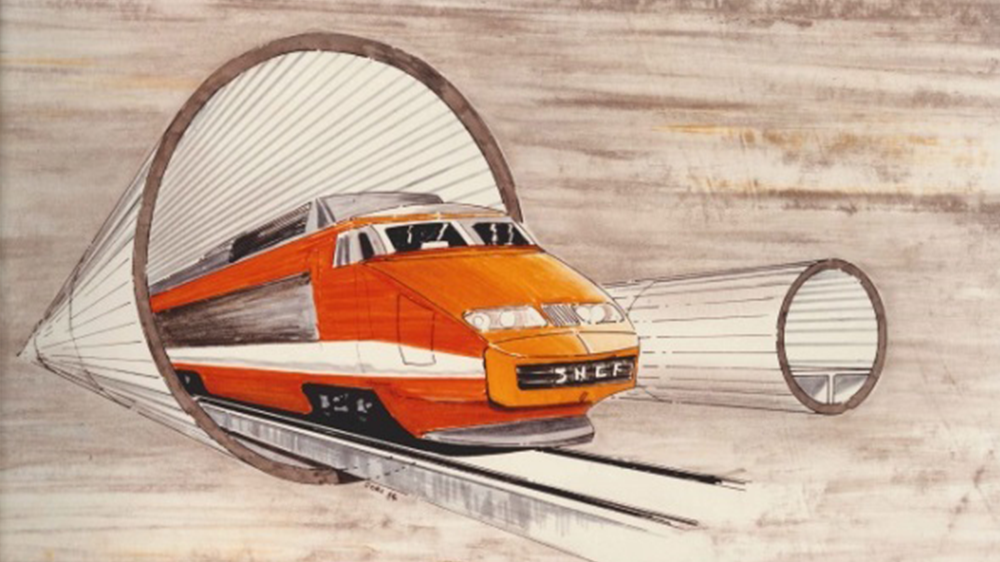

Above: One of the original proposals for the Channel Tunnel. Image courtesy of BNP Paribas Historical Archives.

The plan was two tunnels expected to cost USD $3.5BN. In the end it ballooned to more than $15BN in today’s money - and some reports say it was upwards of $21BN.

Construction works began in 1988.

First the engineering and design teams had to figure out exactly where the tunnels were to be dug. The geology of the seabed was carefully examined. At the bottom of the English Channel is a thick layer of chalk, but below that is a layer of chalk marl which is easier to bore through.

The service tunnel was the first to be excavated so that engineers could see what the ground conditions were like before the main tunnels were dug.

The tunnel boring machines got to work in 1988.

Five TBMs dug from France while six TBMs dug from the UK. Cast iron segments bolted together and precast concrete rings were used to line the tunnels after the TBMs had dug through them.

An enormous amount of chalk was excavated throughout this process and transported back through the tunnel using conveyor belts. On the British side, engineers used the chalk to build a platform at the foot of Shakespeare Cliffs near Dover.

One of the most difficult tasks on the Channel Tunnel project was making sure that both the British side and the French side actually met up in the middle.

Special lasers and surveying equipment was used. However, with such a large project, no one was 100 percent certain that the technique was going to work.

By 1990 the two sides of the tunnel were due to meet up. It came at a point in construction where many feared the project might not ever be completed.

It was plagued by severe cost, schedule, and safety problems. But in December the two sides of the service tunnel finally came together. The technique had worked.

Two workers, one British and one French, shook hands through the opening.

Above: British and French teams achieved the first historic breakthrough in 1990. Image courtesy of Getlink.

For the first time in modern history, you could walk from Britain to France. Then, in 1991 the two main tunnels were connected and things kicked up a gear.

Crossover tunnels, land tunnels from the coast to the terminals, piston relief ducts, electrical systems, fireproof doors, the ventilation system and train tracks all had to be added.

Finally by 10 December, 1993, the first test run was completed through the entire Channel Tunnel. And on 6 May, 1994 the route officially opened.

Thirty years later more than 20M people use this incredible piece of infrastructure every year. And those three tunnels have connected an entire continent. It goes to show once again the remarkable power of construction.

This video and article contain paid promotion for Masterworks, you can skip their waitlist here.

Video narrated by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of Chris Heaton, Jeff Lewis, John Baker, Tambo, Graham Burnett, Thatcher Archives, BBC Archive, Getlink, BNP Paribas Historical Archive and Crossrail.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.