The Battle to Build the Big Apple's Little Island

- Youtube Views 847,190 VIDEO VIEWS

NEW YORK CITY’S iconic waterfront just got a radical addition.

Rising from the Hudson River, this 2.4 acre floating park that cost more than $260 million to build has been described as an oasis for New Yorkers, pushing the bounds of what a public pier can be.

“In a sense, the surprise is that New York has seen through extraordinary projects,” Heatherwick Studio founder Thomas Heatherwick told The B1M. “What are the chances of a project like that really happening?”

Above: The B1M's Fred Mills interviewing Heatherwick Studio founder Thomas Heatherwick.

Between a massive donation from a local billionaire and numerous legal battles, the project hasn’t come without controversy.

“As a space, it's tiny and beautiful, like a little jewel, kind of a microcosm of Manhattan's place in New York City,” City University of New York Professor Sharon Zukin said. “But it represents this terrible dilemma that New York is in and has been in for many years. It has increasing amounts of public space, but decreasing public funds to deal with them.”

This is Little Island – New York City’s new park on the water that almost never got built.

Little Island rises from the remnants of Pier 54, a historic point of entry along the Hudson River. In the early 1900s it was used by those traveling across the Atlantic, and was where survivors of the Titanic returned to safety. And during the 1970s and 80s the piers were used as a gathering place for the LGBT community.

Above: Cunard and White Star Lines at Pier 54. Image courtesy of New York Public Library.

Pier 54 was eventually run down and fell out of use, so the city held a design competition to revitalise the area over the water. Heatherwick’s pitch for Little Island came at a turning point in the importance of New York City’s waterfront development.

“Of all days, our final presentation was on the day of Hurricane Sandy,” Heatherwick said. “We presented in the morning and Hurricane Sandy hit in the afternoon and into the evening and during the night. And so it was extra emphasising the toughness that any piece of river infrastructure needs.”

In 2014, the new pier was officially proposed as a partnership between billionaire couple Barry Diller and Diane Von Furstenberg and the Hudson River Park Trust. It would be a futuristic public park with a live performance space that also happened to be in their neighbourhood.

It was originally dubbed Pier 55, though it was more casually called “Diller Island.” Diller and Von Furstenberg eventually rebranded it as “Little Island.”

Above: Billionaire couple Diane Von Furstenberg (left) and Barry Diller (right) contributed $260 million to the construction of Little Island. Image courtesy of David Shankbone.

“If you build a public park across the street from your house, doesn't your house gain value?” Professor Zukin said.

Heatherwick said he doesn’t think Little Island is a substitute for projects like this being constructed in the Bronx or Harlem. “Projects should be happening of this level of ambition in every borough and in every part of all types of cities,” he said.

The project faced several lawsuits, notably from the City Club of New York, raising a number of concerns about environmental reports and competitive bids. After so many legal battles, Diller pulled his funding in 2017, but New York governor Andrew Cuomo stepped in to save the project.

Altogether, the City of New York contributed $17 million to the scheme, the state gave $4 million and Diller and Von Furstenberg gave roughly $260 million, pledging an additional $120 million to maintain it over the next 20 years.

To be clear, that is a huge donation. Most major public works donations are in the tens of millions, not hundreds.

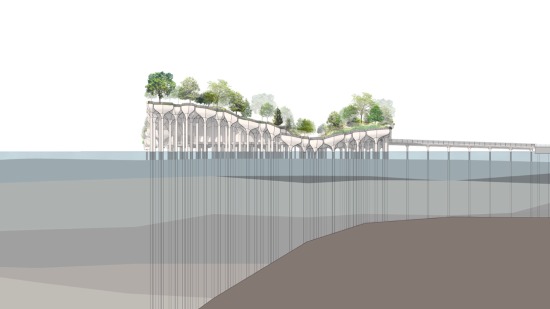

Above: Rendering of Little Island. Image courtesy of Heatherwick Studio/MNLA.

Heatherwick Studio and MNLA worked together to design the park, and engineering firm Arup created the unique pot structures using 3D parametric scripts.

Little Island sits on 132 tulip-shaped concrete pots rising out of the water where Pier 54’s old wooden piles once were. The engineers used precast concrete to form the basis of the structure. That helped the team avoid challenges of casting concrete over a river and the expense of steel construction.

Though the pots look unique, each was modelled using “a Cairo pentagon” pattern that allowed for slight variations from the basic pentagon design. The pots were then cast offsite in smaller parts then shipped and assembled on-site.

Above: Little Island's concrete pots were fabricated off-site. Image courtesy of Arup/Harry McFann.

The entire park is designed to be like a giant sponge for stormwater, as it filters down through the structure where it’s treated below ground and gradually released back into the Hudson.

The island features hundreds of different plants, multiple scenic overlooks, an outdoor amphitheatre, smaller stage, picnic grounds and food and drink vendors that sell $10 avocado toast. It’s open to the public from 6am until 1am, though the park’s capacity is monitored. If you want to enter after noon you’ll have to book a free entry reservation.

“People who study public space and are concerned about privatisation feel a gut wrenching tension that you have a very contradictory space with public ownership, public access, but private management,” Professor Zukin said.

This isn’t New York City’s first attempt at revitalising its piers. In 1995, private funding revamped several piers on the Hudson to create a 28-acre waterfront sports village at Chelsea Piers. More recently, Pier 26 was opened to the public, featuring an open lawn and sports area. And now a public beach is being developed on the Gansevoort Peninsula near Pier 53.

Above: Little Island opened to the public in May 2021. Photo courtesy of Little Island/Timothy Schenck.

Little Island also isn’t Heatherwick’s first controversial public-private partnership. He designed the ambitious Garden Bridge project in London, which was ultimately killed before it ever got built.

“This shows what London missed,” Heatherwick said. “Little Island was involved in politics, it got stopped, but some politicians came together who had a bigger vision about the strategic value for a city. In a way it's useful, the pier existing, because it shows us that what seemed like fantasy in London wasn’t that.”

In the end, Little Island’s opening proved to be both a political and logistical feat. Whether or not it’s what New York needed, it’s a striking addition to the ever-changing waterfront. And it goes to show what a little persistence, and some millions of dollars, can get you in this city.

Narrated by Fred Mills. Footage and images courtesy of The Dronalist, The New York Public Library, Heatherwick Studio, MNLA, Arup, Little Island, Timothy Schenck, Harry McFann, Michael Grimm, David Shankbone, Diana Robinson, Chelsea Piers, Fred George, James Corner Field Operations and Hudson River Park Trust.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.