This 270-Year-Old Building Has a High-Tech Secret

- Youtube Views 408,811 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotion for IES.

THE FIGHT against climate change is one of the biggest challenges of our time, and cities everywhere are coming under pressure to act fast.

Glasgow is on a mission to become ‘climate resilient’ in under a decade and seeing how technology can help to bring its buildings up to future standards.

One experiment is already underway – and in a part of the city where you’d least expect.

Above: Glasgow is Scotland’s most populated city and a place steeped in history.

A former powerhouse of shipbuilding and trade, Glasgow was nicknamed Second City of The British Empire for much of the 19th century, raising its reputation on the world stage.

More recently though, it found itself at the centre of global attention once again – but for a very different reason.

In 2021 it hosted COP26, where hundreds of world leaders and activists came together to tackle climate change.

But Glasgow’s commitment to the environment didn’t end there; it’s also pledged to become net-zero carbon by 2030, and one of Europe’s most sustainable cities.

Net-zero is where greenhouse gas emissions have been dramatically reduced, and any remaining emissions are offset.

“We believe that there's many solutions to get us to net zero; there's no silver bullet,” Alex MacLean, head of consultancy services at Glasgow City Council, said.

“The accounting of carbon when it comes to the value of existing structures is something that we're developing and trying to understand better so that we make that part of our process – always use our existing buildings, especially old listed and important heritage buildings, first before we build something new.”

The city has already shown what it can do. The Athletes Village for the 2014 Commonwealth Games was turned into an energy-efficient housing development with a low-carbon heating system – all on former industrial land.

And now it’s set to embark on another climate-friendly transition, but this time in one of the city’s most beautiful and historic spots – Pollok Country Park, the largest green space in the city.

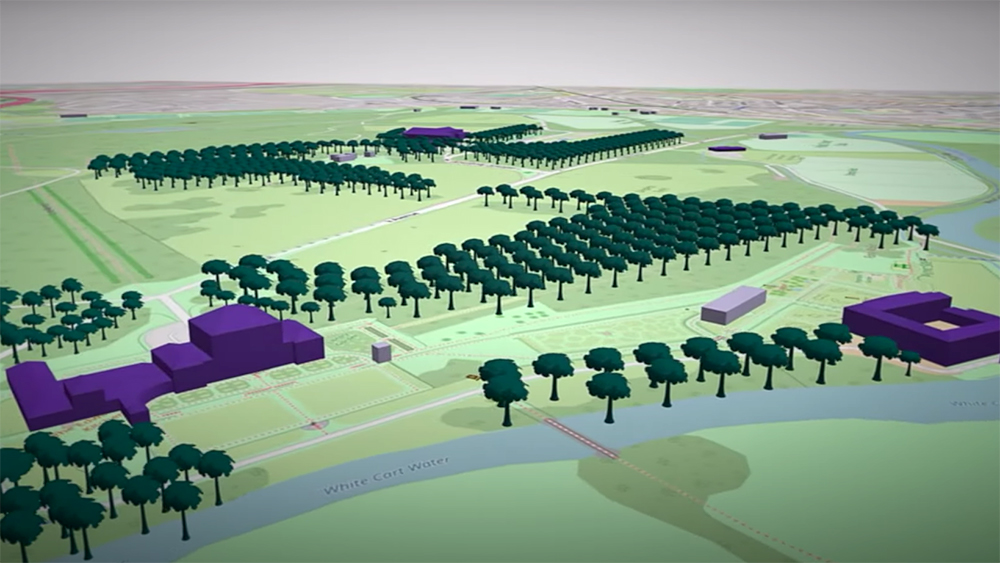

Above: As well as being a sanctuary for visitors and wildlife, Pollok Country Park is home to a number of notable buildings, and one fascinating renovation project.

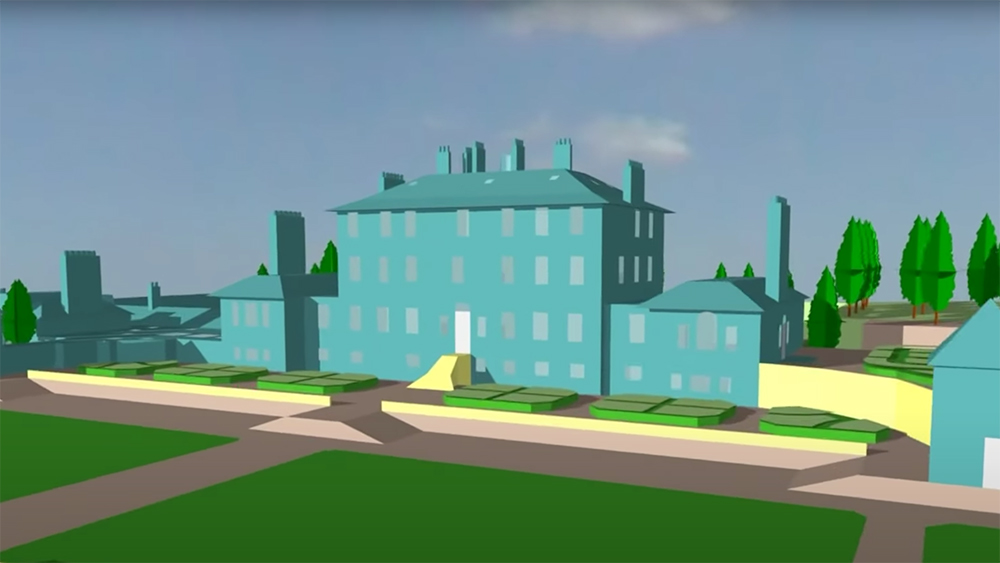

At the centre of the park is Pollok House, a magnificent Georgian mansion built in the 1700s. It’s the ancestral home of the Maxwell family, who were a pretty big deal around here for several centuries.

The Maxwells have owned land in the area since the 1200s. One of their most famous members, Sir John Maxwell, fought for Mary Queen of Scots at the Battle of Langside near here in 1568. The house was gifted to the City of Glasgow in the 1960s and more recently became known as Scotland’s Downton Abbey.

This isn’t the largest attraction in the park, though. That title goes to the Burrell Collection. It’s been labelled one of Europe’s most beautiful museums, with thousands of artworks and artefacts from all over the world.

Next door is Knowehead Lodge, built over a century ago for staff at the estate – like the gamekeeper or gardener – to live in. Today it’s used as an office for the park’s management. On the banks of the river is the Old Stable Courtyard. It has a gateway from the Renaissance period and a wall section that’s thought to have originally belonged to the medieval Laighe Castle in the 1500s.

£13 million of government funding is being used to turn it into what’s being called a Living Heritage Centre.

Above: The Old Stable Courtyard is currently derelict but now being restored.

“We're going to showcase renewable energy generation on the river and we're going to provide educational facilities for local people and schools to come and have a base within the park and really make use of this venue and this attraction that we have,” explains Alex Fleming-Knox, programme liaison officer at Glasgow City Council.

Apart from the museum, which has had a £68 million makeover unveiled by the king, most of the buildings in Pollok Park haven’t changed much in a long time.

But now these treasures of the past are being equipped with cutting-edge new tech as part of a plan to transform this whole site into a new kind of energy laboratory. The idea is to make the site energy independent, meaning all power is generated and used off-grid.

This would mean reducing the carbon emissions of these old buildings significantly, while investing in renewable energy.

Deciding how best to achieve this, though, is not simple. In fact, it’s difficult to know where to start. That's why a digital twin of the entire park has been created by IES, a Glasgow-based tech company specialising in the decarbonisation of buildings and cities.

Digital twins are virtual replicas of a physical asset. This can be anything from a single object to a group of buildings.

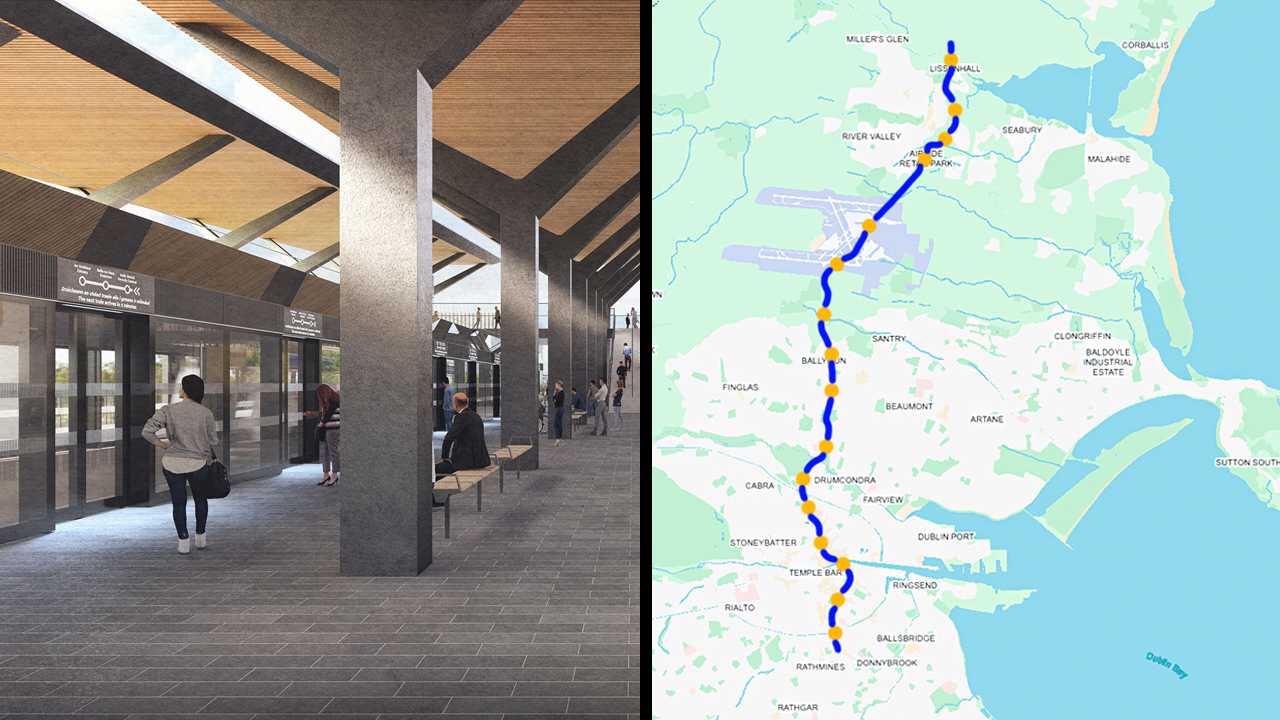

Above and below: The IES digital twin of Pollok Country Park. Image courtesy of IES.

“It's based on physics-based simulations of the buildings and also uses metadata from the site – so from sensors, from building management systems – and it collates the two together to really create a digital asset which behaves every moment in time like the real building,” Valeria Ferrando, associate director of the ICL Consultancy at IES, said.

In this digital twin, the main buildings have been recreated using the IES Virtual Environment, giving precise information on how energy is used all over the park.

The models also show how consumption can be reduced and where improvements can be made. Several possible scenarios were modelled in the digital twin to show the impact they would have.

“The scenario modelling was really important to understand what the potential future outcomes might be, what the most cost effective solution would be in terms of reducing the carbon footprint,” Fergus Ross, ICL project manager at IES, said.

“We were able to test all the different options in terms of which buildings can be connected to which generation sources and work out the best way forward.”

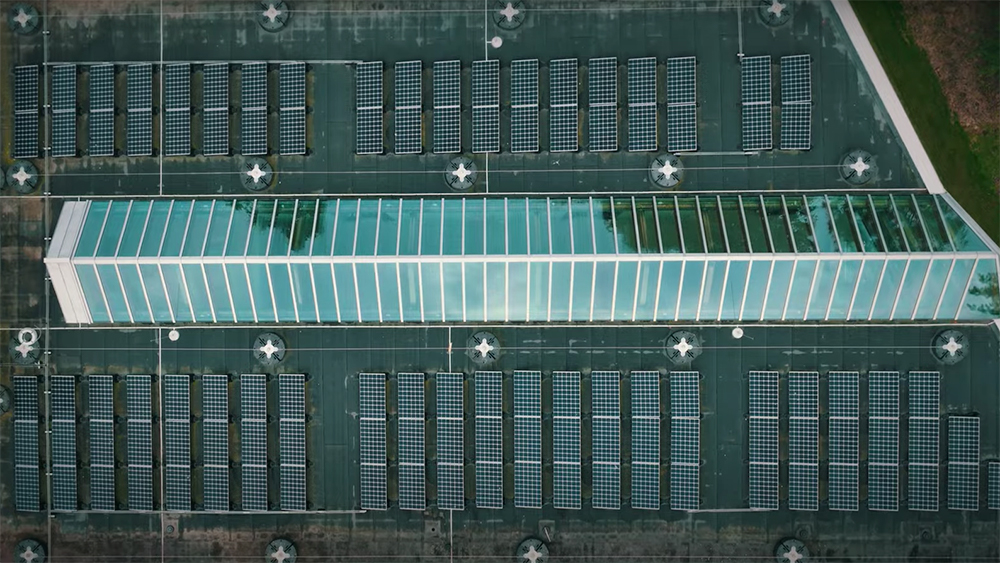

They included interconnecting all of the buildings’ heat and electricity networks and installing 4MWh of battery storage and 3,000 square metres of solar panels. That might sound like a lot, but all together they do require a fair bit of power – largely thanks to the Burrell Collection.

Above: Over two thirds of the park’s energy is used by the Burrell Collection alone.

It has a large floor area and needs to run cooling and dehumidification systems for all of those museum pieces.

A new hydroelectric turbine, fed by the river, is set to be installed at the site of the old sawmill, which could end up powering Pollok House with renewable energy.

“The data we will get from the digital twin will allow us to become better operators when it comes to managing energy,” MacLean said. “It's not just about designing something, it's about operating and optimising the energy you've got.”

Results showed that if all the upgrades were carried out, it would lead to a 34% reduction in carbon emissions across the estate.

The software also enabled custom dashboards to be set up – offering live data at a glance or in detail.

Playing by the rules

Upgrading old buildings to become energy efficient is not straightforward. Pollok House and the courtyard are Grade A-listed, meaning there’s a limit to how much work can be done.

They require a lot of heating too due to having stone walls, and because, well, it’s Scotland.

It means a lot of the improvements you might do to a modern building to make it more energy efficient, like wall insulation or double glazing, is out of the question. But that doesn’t mean you can’t change where that energy is coming from, and that alone can make a big difference.

The museum has already shown what’s possible. During the refurb, vast amounts of solar panels and LED fittings were put in.

Above: The Burrell Collection's renovation cut energy consumption by a quarter.

In a country where 80% of the buildings we’ll have in 2050 have already been built – many of them already quite old – these sorts of projects need to start happening in a lot more places.

The hope is this popular site becomes an example of what can be done as the city tries to hit that 2030 net-zero target.

“It's the first time we've used a digital twin outside of one big building,” MacLean said. “So trying to have that network of buildings and think about energy flows and generation across a series of buildings – well, that's what we'll need to do in the city. It is our intention to use this as a learning exercise.”

When visiting a place like Pollok Country Park you can’t help but think of the past and what must have happened there centuries ago. But now that we’re in a climate emergency we have to look to the future and how our built environment can help get us out of it.

Yes, a lot of that will come down to how we build new projects, but we have to make sure our existing buildings – even iconic ones like Pollok House – are part of it too.

This video contains paid promotion for IES. Discover how digital twins can help decarbonise the built environment.

Video presented and narrated by Fred Mills. Special thanks to IES, Glasgow City Council and National Trust Scotland. Additional footage and images courtesy of IES, CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Collections, National Trust for Scotland/Pollok House, Channel 4, Commonwealth Games Federation, DW News, Granada Television, The Scottish Sun, Sky News and Solar Trade Association/Forster Energy/CC BY-SA 2.0.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.