The Battle to Build Taiwan’s Strangest Building

- Youtube Views 361,966 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotion for Bluebeam.

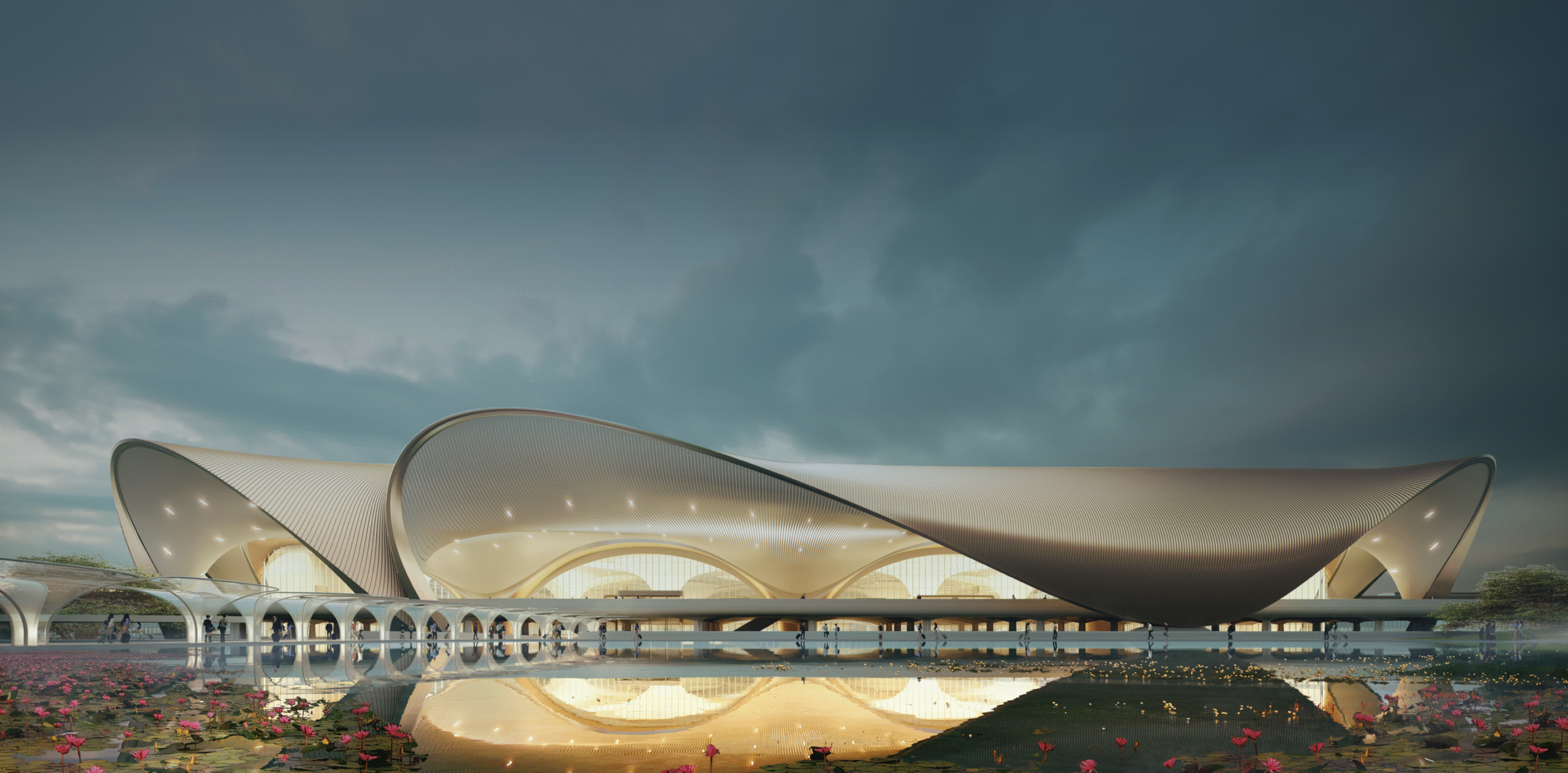

IN 2015 the mayor of Taipei stood above this bizarre and misshapen construction site and threatened to “strangle every single one” of the contractors if it could not be completed.

Despite this public and rather impassioned threat, it would be another seven years before the building finished.

USD $80M over budget, a decade under construction, and one of the most important cultural buildings in Asia ...

This is the story of the Taipei Performing Arts Center, the building that nearly broke Taipei.

You may have noticed Taiwan has been in the news a lot lately.

If you look back to this time last year you’ll remember former US speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi took a trip to the island nation.

It was the highest-profile visit by an American politician to Taiwan in 25 years - and in response Beijing launched a barrage of joint military exercises. It was a big deal.

Above: The Arts Center under construction. Image courtesy of OMA photography by Chris Stowers.

Against this backdrop the long gestating Taipei Performing Arts Center finally opened.

Some would see it as a chaotic beginning for a building with a long and chaotic history. But the defiance of Pelosi’s visit - whether or not you agreed with it - and the opening of this theatre are more closely connected than you would think.

In order to understand this, we have to rewind the clock back to 2008.

Taipei launched an international competition to find a design for a set of theatres to be built on the site of the Shilin Night Market. These buildings would be an icon for culture and help legitimise the tiny nation on the world stage.

Think of what the Guggenheim did for Bilbao, or the Opera House for Sydney. A building - especially a cultural building with government money - is never just a building. It’s a statement.

Dutch architecture studio OMA had no interest in chasing icons, nor did it want to create a wholly generic theatre. So it set about creating something else.

With no expectation of winning the competition the architects designed with freedom, which is probably why they won.

The first thing they did was decide to keep the night markets, seeing them as a vital part of the city and a unique way to combine so-called high culture and low culture.

Not only did they keep the night markets - they drew inspiration from them.

Their performing arts centre packs a lot into a small space.

There's the Globe Playhouse - an 800-seat spherical theatre, designed to resemble a planet docking against the cube, the Grand Theatre - a 1,500-seat space, and the Blue Box - which will be used for more experimental shows.

Instead of giving each theatre its own back of house and its own entrance, these features are brought together.

Above: The building took more than a decade to finish. Image courtesy of OMA photography by Chris Stowers.

Lifting the theatres up above the ground leaves space outside free for public use. This unorthodox method then created an opportunity for invention.

The Grand Theatre and Blue Box could be connected, creating a super theatre 100 metres in length.

This was an ambitious project. And the challenges to build it were immense, the building is essentially a central volume with the theatres floating out at varying angles.

There are cantilevers, enormous domes, and earthquakes to worry about.

In order to allow for architectural freedom - and to prevent these floating spaces from falling to the ground - the faces of the central cube were turned into a stiff braced steel box carrying the building’s lateral loads and much of the gravity force.

This worked in combination with columns beneath the auditoria to support and stabilise the three projecting volumes.

Taipei is famously prone to earthquakes - sitting right in the middle of the ring of fire - so the arts centre had to be engineered to be earthquake-proof.

The whole superstructure is base-isolated - essentially meaning the building is lifted up and separated from its base. In the event of an earthquake the ground will shake but those in the building will only feel about 40% of its force.

The globe theatre itself cantilevers 26 metres from the main cube. This is accomplished by three-dimensional space trusses occupying the space between the auditorium and outer shell.

Despite its complexity, this globe theatre - a modern nod to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London - was designed with functionality.

Because of its unique shape audience members sit in a curved plane closer to the stage, allowing more visitors a better experience of the theatre.

This democratisation continues in other elements of the building’s design. There is a public loop that runs through the entirety of the building allowing anyone to come and see the inner workings of the theatre at any time without a ticket.

Above: The theatres are made to be floating volumes floating off the central back of house. Image courtesy of OMA photography by Chris Stowers.

The whole project was due to complete by 2013, but construction didn’t even start until 2012.

It even bankrupted the main contractor and by 2015 mayor Ko Wen-je delivered his infamous threat. The budget soon ballooned from USD $120M to $226M.

Then the pandemic hit and the lead architects Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten had to finish their arts centre from Europe, via Zoom.

But come 2022 the project was finished and opened to the public. This small theatre with a big vision. A democratised version of theatre built next to the hub of the city’s nightlife. A theatre for everyone.

While China flew its planes overhead Taiwan opened its theatre with the hope that culture could be an even greater weapon.

A building is never just a building. Like the Guggenheim in Bilbao and the Opera House in Sydney.

This building is about freedom and it’s about expression. It’s about the Taiwenese identity standing in defiance. Defiance of gravity, defiance of budget, defiance of the chaos around it.

It may look bizarre and disjointed, or maybe beautiful and daring. But it’s definitely not constrained.

This building may have nearly broken Taipei, but it could make this city too.

Clarification: The information that the contractor was bankrupted by the Taipei Performing Arts Centre (TPAC) was sourced from the South China Morning Post. According to other sources, the contractor was bankrupted for multiple reasons. The project was originally scheduled to finish in 2013 but the timeline was pushed back due to site conditions discovered after the competition phase, according to OMA.

Correction: In Taiwanese currency, the budget of the TPAC went from 4.8 billion TWD to 6 billion TWD, according to OMA.

This video was powered by Bluebeam. Struggling to reduce project costs? See how much Bluebeam can help with our ROI calculator here.

Additional footage and images courtesy of OMA, Chris Stowers, Iwan Baan, Shephotoerd Co. Photography, ABC News and Sky News.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others but please be nice and play by our rules.