Why Architects Put Trees on Buildings

- Youtube Views 1,209,867 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion by FOREO.

LOOK AT almost any skyscraper that’s been proposed in the last decade or so, and you might notice a budding trend.

They all have trees on them – and it all seemed to start with the controversial high-rises in Milan - Bosco Verticale.

Now, green-covered towers aren’t just meant to stand out like giant chia pets across drab glass and concrete skylines. Vertical forests like this aim to improve our cities by cutting CO2, providing shade, attracting wildlife and even improving our mental health.

But when you take off the rose-coloured glasses, just how green are these green skyscrapers? How is vegetation even maintained so high above the ground? And if it’s such a no-brainer why doesn’t every new building look like this?

It’s time to dig up the truth under these forests in the sky.

Above: One Central Park in Sydney, Australia.

Architects sticking trees on new building renders is becoming a bit of a joke. It’s now so common that light-hearted suspicions of some kind of automated AI programme or a senior partner sprinkling trees on projects just before things go out the door have been doing the rounds.

Some question the cost and maintenance that adding trees brings versus the benefits. So is this just a shallow trick to boost social media or commercial interest in projects and make them feel sustainable – or is there a genuinely more noble purpose?

Well, to really answer that you need some more context, and that means zooming out a bit.

Take a walk through cities like New York, London, or Tokyo and they seem massive. But compared to all of the Earth’s land, built up areas really only take up around 1% of the space.

And yet – our urban areas are responsible for about 70% of global CO2 emissions, and skyscrapers and cars are among the main culprits.

While many of us might not realise it, if we really want to tackle climate change it’s kind of essential that we build and use our buildings, cities and transport systems in a much more sustainable way.

Expanded public transport, better building insulation, renewable power sources like solar and smart temperature systems can all help with this – and so can greenery.

So how exactly did this trend plant its roots?

Well it’s not entirely new, but while there have been green roofs and garden roofs for centuries – we can kind of pinpoint the start of the current trend to one little spark over in Milan.

This is Bosco Verticale – or Vertical Forest – which completed back in 2014. Designed by Italian architect Stefano Boeri, the two high-rise towers are covered in thousands of trees and shrubs and stand at 112 and 80 metres tall respectively.

Above: Bosco Verticale in Milan, Italy.

Since this building came on the scene, similar structures have popped up all over the world.

There’s One Central Park in Sydney, Agora Garden Tower in Taipei, and the Oasia Hotel Downtown in Singapore. In fact the tree thing really is happening everywhere.

Now, while Bosco Verticale may be considered very influential, at the time of its construction it wasn’t exactly popular. Critics thought the idea was too ambitious and that nature at such high altitudes simply wouldn't work.

Fast-forward to today and its greenery is clearly thriving – although, as you might have guessed, building and maintaining structures like this isn’t all sunshine and daisies.

The residential towers themselves may have been relatively simple in design – but the added greenery created entirely new challenges.

Before construction started, architects studied vegetation in the area, consulted experts in the field and looked at average weather conditions. They then tested and monitored plants in high-wind conditions before picking and choosing what vegetation could be planted and where.

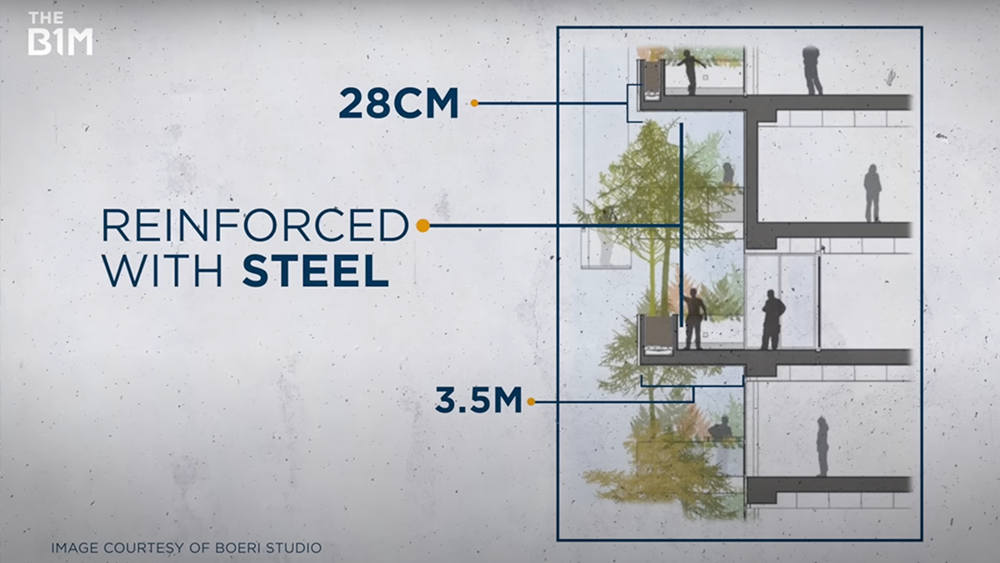

Structurally, the project team used a customised framework and scaffolding layout. Each of the concrete balconies are 28cm thick, extend 3.35 metres outwards in an irregular arrangement and are reinforced with steel to carry the extra load of vegetation.

Above: The balcony structure of Bosco Verticale.

Once the building superstructure was complete, the largest and most vulnerable trees were restrained within steel safety cages. Other plants sit inside concrete containers that range in size.

Since its completion, the building’s vegetation has been regularly monitored and maintained. A unique centralised irrigation system uses recycled rainwater and keeps the plants nourished.

There’s also a crew of specialised arborists dubbed the Flying Gardeners that hang down the side of the buildings every few months.

"There's usually a pipe system that tells that there are a few passive systems where the water cascades down through it," director of Green Infrastructure Consultancy Gary Grant said.

"But most of them you've got a pipe system which is controlled by computers. So the amount of water that gets to the plants is correct for the plants and for the climate and so on. "

While the tree-covered building trend has continued to grow all over the world, there’s more to it than just creating some very nice looking architecture.

For one, plants are known to have positive impacts on mental health. One study found that seeing vertical vegetation within a city led to lower stress levels and less negative emotions, compared to areas without greenery.

"The other big one is summer cooling," Grant said.

So if you've got soil and vegetation on anywhere, actually in the heat of summer, you're getting shade and evaporative cooling. And so that's reducing air conditioning demand. So that could be a big plus because that can save our electricity consumption on some of these schemes."

After about 20 to 30 years of that reduced use in your typical building – things start to really add up in terms of cost savings and overall carbon footprint.

And the benefits don’t stop there.

"The ultimate big one is biodiversity," Grant said.

So we know that by choosing the right plants in the right combinations, we can really make the urban area more attractive to wildlife birds, especially like there's a lot of birds to feed and nest in these features."

Ever since its construction Bosco Verticale has exploded with wildlife. According to the architects, it provides a habitat for over 1,600 bird and butterfly species – though, that in itself creates a maintenance issue.

It’s also not just an upgraded structure that buildings like this need to think about.

To prevent water getting inside, Bosco Verticale, and green roofs in general, have a waterproofing and drainage layer between the growing medium and structure.

Fire is another critical area. Many national building codes demand that designers and engineers prevent fire from being able to spread up a building through its external cladding or facade, or to design systems that protect occupants and the structure’s overall integrity should that happen.

Any trees or plants need to be added and then maintained to meet those specific national rules. Typically that means keeping them to a certain size, preventing them from becoming too dry and incorporating the right fire suppression and evacuation systems.

Despite the touted-benefits of adding trees to our buildings, it’s perhaps telling that we haven’t seen an explosion of fully completed projects looking just like Bosco Verticale. In fact, very few structures have even tried to come close.

The Spiral in New York was pitched as a lush addition to the concrete jungle. But now that it’s complete, its greenery feels like a far cry from the renders – though, granted it’s still early days.

Many other schemes go for a sprinkling of trees rather than attempting a full blown forest, and the finished results can often end up a long way from what was shown in the design renders.

Above: A rendering of a skyscraper with trees at 8 Shenton Way in Singapore. Image Courtesy of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.

But it’s not just other projects falling short. Some believe that Bosco Verticale feels like a stand-out anomaly because it had a helping hand.

"The real project gets built right before the Milan expo," Aprilli Design Studio founder Steve Lee said.

So it's like the government helping them have that project as a showcase project for the city, and that doesn't happen all the time. These kind of projects all have legal challenges that you have to go over like the court issues because you haven't seen it before. When it comes to, let's say in New York or like some cities that have long history and like code issues, then it's a whole other game."

As you might be gathering, adding trees isn’t a stroll through the park.

Balconies need an immense amount of concrete to carry the extra weight. That means stronger foundations and superstructures, and extra cost. On top of all that concrete production is a huge source of CO2. In 2021, the cement industry accounted for 7% of all global emissions.

So while extra trees in an urban environment may reduce carbon over a period of time, the concrete can actually add to it in the initial construction phase.

There’s also significant long term maintenance both for upkeep and safety, and those added fire considerations – all of which, again, adds more capital and operating cost.

For some it feels like just adding a few trees at the render stage is a move to win over planners, reassure local communities, close real estate deals and get your Instagram like-count up.

And that’s an important bit of context. Many new projects need public and commercial support in their early stages – and ensuring a good reception to your renders in the media can help win over both those constituencies. Trees are popular and can help soften developments.

"Designers are very attached to making it visually look cool," Lee said.

But actually, if you ask these serious questions, does it really impact the tenants or the city itself, the surrounding environment? Nobody has really given proof that it significantly improves anything, but in principle it does. It's supposed to have some great impacts in the future."

Those impacts largely remain to be seen but may become more seriously sought after as the fight against climate change grows in urgency. They’ll certainly come under more scrutiny.

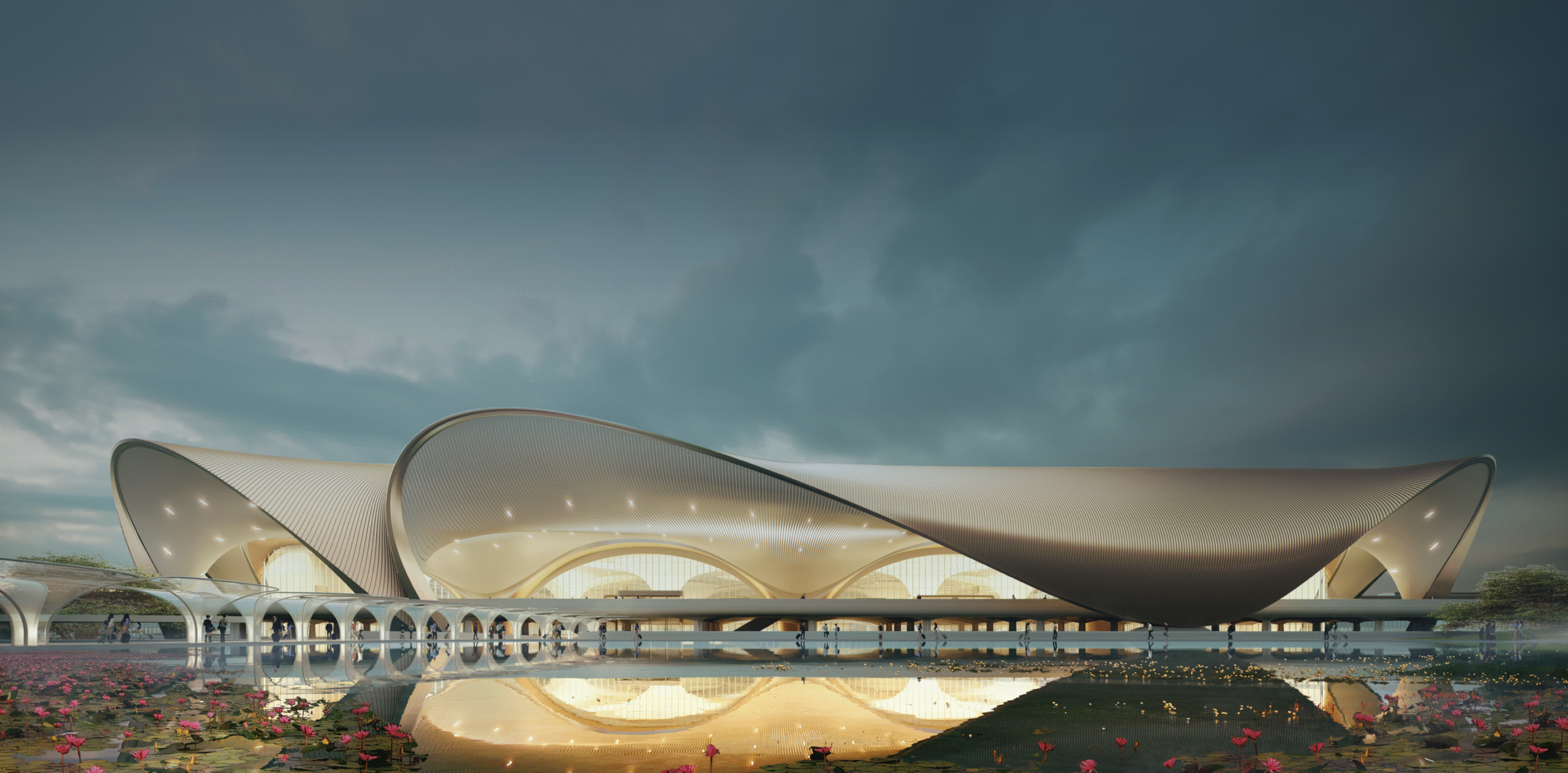

For now, architectural renders continue to feature plenty of trees and that could be a sign of what’s to come over the next decade as these projects get built. Boeri alone – one of the few practices with a proven track record in this area – has already proposed concepts for an entire forest city, a stadium, and more.

While many doubted the initial idea of vertical forests, the concept is clearly now branching out. Whether or not it becomes a widespread, genuinely impactful and long term part of our urban fabric will take years to discover.

This video contains paid promotion for FOREO.

Special thanks to Steve Lee and Gary Grant. Footage and images courtesy of WoHa Architects, Bjarke Ingels, Studio Gang, Boeri Studio, Buro Old Scheeren, SOM, Brick Visual, Alison Brooks Architects, RMJM, Emilio Ambasz, Heatherwick Video and The Dronalist.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.