Building a Nation's Capital: Washington D.C.

- Youtube Views 401,334 VIDEO VIEWS

WASHINGTON D.C. - the landmark packed capital of the United States of America - is one of the most recognisable cities in the world.

Its iconic collection of impressive buildings and monuments, arranged around the national mall, have played host to countless historic events, marches and speeches.

But creating this impressive backdrop didn’t happen by accident - Washington D.C. is in fact a planned city.

Named in honor of America’s first President, George Washington, D.C. was founded in 1791 to serve as the capital city for the new country that had declared independence 15 years earlier. The United States Constitution authorized the creation of a city to act as a permanent home for the country’s government that would not be part of any state.

Above: Washington D.C. was founded in 1791 to be the capital of the new country (image courtesy of Carol M. Highsmith).

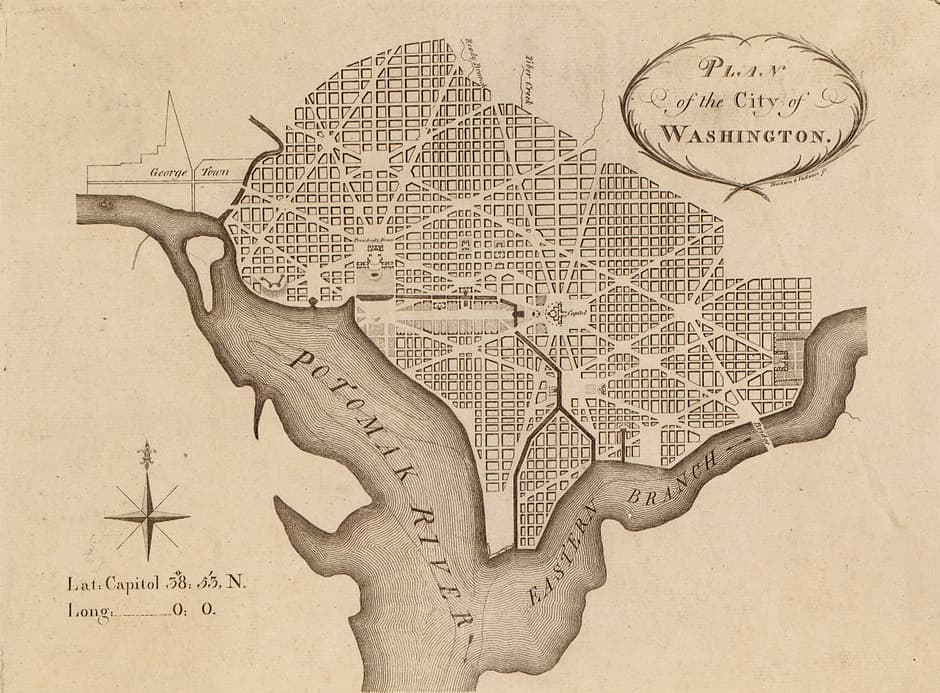

Following a compromise between northern and southern politicians, Washington chose a location on the Potomac River on the country's east coast as the site for the capital.

The states of Maryland and Virginia each donated land to form the federal District of Columbia, (D.C.) which was formalized with the signing of the Residence Act on July 16, 1790.

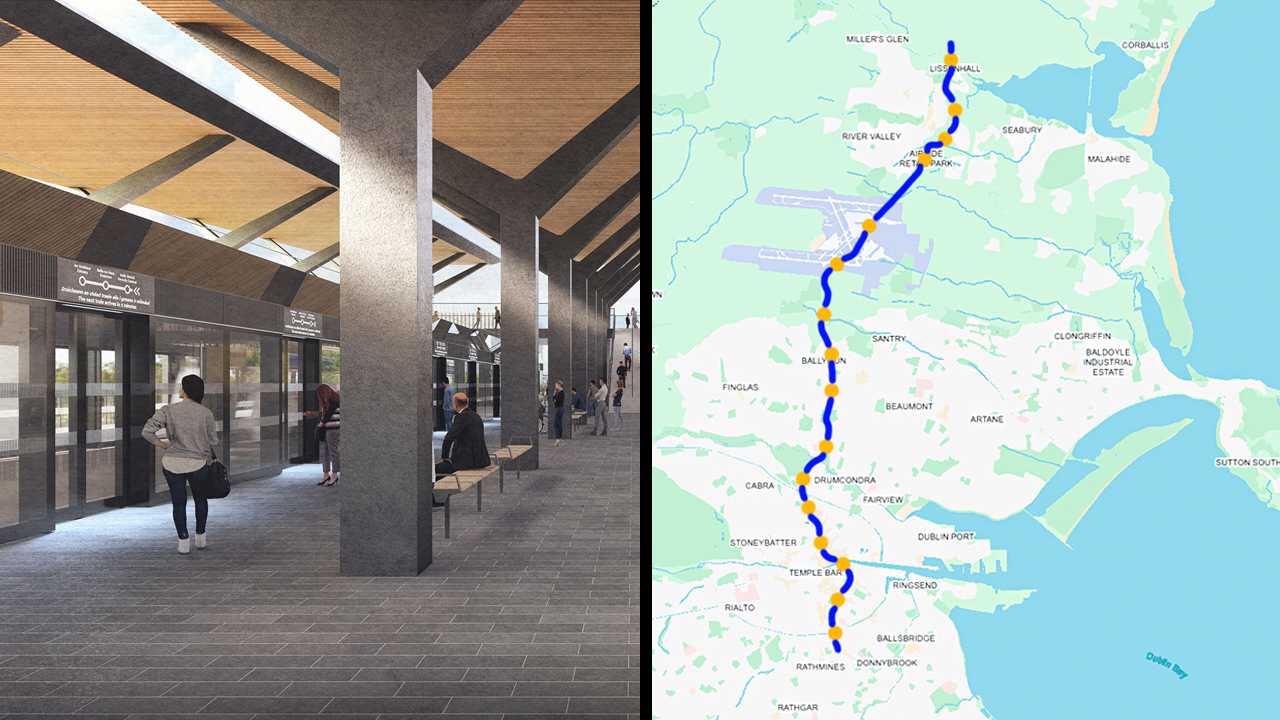

BIRTH OF A CITY: THE L'ENFANT PLAN

To design the modern capital, Washington commissioned French-born engineer and city planner Peter Charles L'Enfant.

Many of the core principles of the city we know today were laid out in L'Enfant's proposals.

Heavily influenced by his native Paris, L'Enfant's plan consists of a grid of streets overlaid with broad diagonal avenues radiating out from ceremonial squares. At the heart of the plan was the U.S. Capitol building, placed on a small existing hill, which L'Enfant described as a "pedestal awaiting a monument".

Above: L'Enfant's plan laid down the core elements of the city we know today (image courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Stretching out in front of the new home for the country’s central government was a garden-lined "grand avenue" approximately one mile long and 400 feet wide which would become known as the National Mall.

WATCH NEXT: WORLD TRADE CENTER RISING

Directly facing the Capitol at the end of this avenue, an equestrian statue of George Washington was planned, with the President’s Mansion – The White House – directly north of the monument.

The mansion and Capitol were joined by a diagonal avenue to complete the triangle.

Following several disputes L'Enfant was eventually dismissed from the project and Andrew Ellicott, who had worked surveying the city, tasked with completing the design.

GROWING PAINS

By 1800 the first two major public buildings of the new city were completed.

The seat of government finally moved to D.C. and President John Adams moved into the residence, which was designed by Irish-born architect James Hoban in Neoclassical style.

Both buildings were re-built after the British burned the city in 1814, and both have been substantially extended since.

Above: Both the White House and the Capitol Building were completed by 1800.

The equestrian statue of Washington planned at the head of the grand avenue did not materialise, and it wasn’t until 1848 that construction on a different monument to the nation’s first President began.

Although the monument was originally intended to be placed at a point directly aligned with the center of the White House and the Capitol, the ground at this location proved to be too unstable to support the vast obelisk that was proposed.

Therefore the monument, designed by architect Robert Mills, stands 390 feet (or 119 metres) to the east of its planned location; much to the annoyance of those that like things lined up.

Above: Construction of the Washington Monument began in 1848 and finally completed in 1884.

Due to a lack of funds, construction of the obelisk was halted between 1854 to 1877, and a clear change in the color of the stones can now be seen about a third of the way up the monument.

Completed in 1884, the 554 feet 7 11⁄32 inches (169.046 m) tall monument remains the world's tallest stone structure, and was briefly the tallest man-made structure in the world, before it was surpassed by the Eiffel Tower in 1889.

Throughout the 19th century L'Enfant’s plan for a ceremonial centre was largely forgotten as the Mall became used for less glamorous activities like bivouacking and parading troops, slaughtering cattle and producing arms.

EXPANSION OF THE MALL

Although the Mall had not been the focus of much attention, it was expanded to the west in the 19th Century.

Until 1881 the Potomac River had run close to the Washington Monument. However, a major flood of the city that year prompted Congress to order the Army Corps of Engineers to dredge a deep channel in the Potomac and to use the excavated material to build up the banks of the river.

This reclaimed land became known as "West Potomac Park" - an area which would go on to become home to many of the Mall’s memorials.

THE McMILLAN PLAN

By the early 1900s, L'Enfant's vision for a grand national capital was under threat, with randomly placed buildings – including a railroad station, greenhouses, and commercial and industrial facilities – encroaching on the Mall.

To rectify this, the Senate Park Commission issued the McMillan Plan in 1902, which re-imagined the Mall as the symbolic centerpiece of a larger, grander federal district.

Above: The McMillan Plan proposed creating a cruciform park to be the symbolic centerpiece of the capital.

The plan proposed creating a cruciform park, with the Capitol building anchoring the eastern end of the east-west axis and The White House the northern end of the north-south axis.

The Washington Monument would stand at the centre of this plan, with new monument’s planned for the south and west ends of the cross.

The plan also eliminated the Victorian landscaping of the National Mall, and replaced L'Enfant’s "grand avenue" with the 300 feet (91m) wide simple expanse of grass we see today. Flanking this open area, a series of low Neoclassical museums and cultural centers were envisioned.

MONUMENTS OF THE MALL

Although the McMillan Plan was not enacted in its entirety, its principles guided the development of Washington D.C. over the next 100 years. During this time, the role of the Mall changed as it became a place of gathering and symbolic memorials.

As the McMillan Plan suggested, the Mall was extended to the west and terminated with the Lincoln Memorial, which, along with the reflecting pool, were completed in 1922. This was followed in 1943 by the Jefferson Memorial, which terminates the southern axis. To place this monument directly in line with the White House builders had to reclaim land from the tidal basin, with the resultant unstable earth still causing problems today.

Above: As envisioned in the McMillan plan the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922 (image courtesy of Wally Gobetz).

These memorials were joined by the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in 1982, the Korean War Veteran’s Memorial in 1995, the FDR Memorial in 1997, the World War II Memorial in 2004 and the Martin Luther King Jr Memorial in 2011.

The Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building was also joined by a succession of museums at the east end of the Mall. This has created a significant museum complex that contains 11 buildings and attracts some 28 million visitors each year.

The Mall continues to develop and the latest museum – the National Museum of African American History and Culture, designed by Sir David Adjaye – opened in 2016.

Above: The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the latest addition to the Mall (image courtesy of Darren Bradley).

Although Washington D.C. was pre-designed and planned, it has been a work in progress for the past 200 years and is still developing today.

L’Enfant’s plan provided the framework for a modern city that has evolved to become the memorial filled administrative and symbolic capital of the world’s most powerful nation.

Love construction history documentaries? Watch more in our free series.

Images courtesy of Carol M. Highsmith, Howard Chandler Christy, E. Sachse, Library of Congress, Filipe Lourenco, Brook Ward, Wally Gobetz, Joe Ravi, NPS Photo, Harrison Jones, Kačka A Ondra and Darren Bradley. We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.