Why It’s So Hard To Find An Affordable Home

- Youtube Views 2,449,416 VIDEO VIEWS

Video presented and narrated by Fred Mills.

THIS is one of the largest regeneration plans in Europe.

In the heart of London, Battersea Power Station has been transformed from an abandoned, derelict site into a shiny new mini-neighbourhood filled with shops, bars, restaurants and luxury housing.

It’s an astounding turnaround of what was once a wasteland. Thousands of new jobs, hundreds of new homes and some 19 acres of public space have been created in the process.

But for the people who already live in the area, new developments like these are a sign that things are about to get expensive.

So why are we seeing so much new high-end housing being constructed in the middle of a housing crisis? What we found was a story of dwindling council budgets, rising land values and government-backed programs incentivising profit-driven developments like this.

The battle to save Battersea Power Station

Before Battersea Power Station was London’s newest mixed use neighbourhood, it was, funnily enough, an actual power station. You might recognise it from Pink Floyd’s Animals album, Dr. Who, Sherlock, Batman, the list goes on.

At its peak, Battersea was supplying a fifth of London's electricity, but it was shut down in the 80s due to air pollution and then sat abandoned for decades. During that time it was granted Grade II listed status, meaning that it is formally protected as a heritage site.

As the years rolled by, ideas for how to repurpose the massive building came and went. Proposals ranged from an indoor theme park to hotels, a shopping mall, football stadium and everything in between.

It wasn’t until 2013 when a group of Malaysian developers successfully began a £9BN project to transform the 42-acre site, creating a brand new neighbourhood full of bars, restaurants, shops, offices and luxury housing.

Above: Construction of Battersea Power Station. Image courtesy of pxl.store / Adobe Stock.

Battersea Power Station is being redeveloped in no fewer than eight main phases – with the first four laid out so far.

Phase One was building a new apartment complex which was completed in 2017. Phase Two was converting the old power station into new shops, apartments, offices, restaurants and an event space. That’s set to open to the public in autumn 2022. Phase Three is to construct a brand new high street. And Phase Four will be the construction of new affordable housing.

Rent in the new developments ranges from around £2,000 to more than £7,000 a month. If you’re in the market to buy, that’ll be anywhere from more than £550,000 for a studio to more than £7 million for one of the ultra-luxury sky villas.

“Our vision and the vision of our shareholders is that it is going to be a new town centre for Wandsworth and also for London,” deputy chief executive officer of Battersea Power Station Development Company Madonna Kinsey said.

“We want people to come here, we want people to shop, to live, to spend time. So we really want it to be that draw for the local community and the wider area.”

Battersea developers told us they’ve made a lot of investments in the community, through things like creating a community choir, holding a local jobs fair, donating more than 2,000 refurbished laptops to people in Wandsworth, launching a community forum to discuss the new development and contributing over £300M to building a new tube station.

As you might imagine, converting this enormous building from a coal plant into a new mixed-use development wasn’t exactly a stroll along the river.

“Fundamentally, we are using the building in a different way,” senior project director for Battersea Power Station Development Company Jason Cowell said.

“There are a lot of people in the team that feel a bit of responsibility and an obligation to get this right. You know, it's a historic building and there's a huge amount of passion in the team to get this right and to respectfully restore the historic elements of it.”

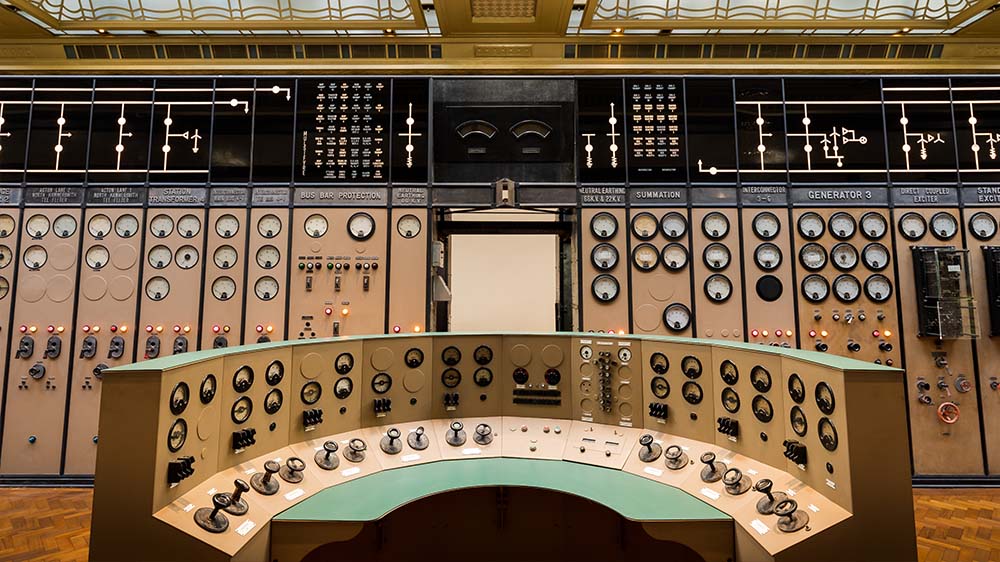

Above: The restored control room at Battersea Power Station. Image courtesy of BPSDC / James Parsons.

The iconic 51-metre tall chimneys were reconstructed using the same jump form technique as when they were first built, using almost 25,000 wheelbarrows of concrete.

The same materials were used to construct the new chimneys, the only thing that’s new are the more modern steel reinforcements hidden inside. Everything else, down to the exact paint colour, was meticulously matched to replicate the originals.

Much of the outside of the power station was also taken apart and rebuilt. The restoration team was so meticulous with the brickwork that they actually tracked down the original manufacturers to create 1.7 million handmade bricks to replace originals where needed.

Even the control room was restored to its original state – and it’s set to be used as an events venue when it opens to the public.

One of Europe’s largest regeneration projects

Now the renovation of the power station isn’t a stand-alone project. It’s part of one of Europe’s biggest regeneration schemes that’s out to transform an entire area of London.

Back in 2012 when Boris Johnson was Mayor of London, he introduced a plan for something called the Vauxhall, Nine Elms, Battersea Opportunity Area. It was essentially a masterplan to take this area of London and transform it into a bustling new neighbourhood filled with new apartments and businesses.

While this is one of the biggest, it’s not London’s only plan to reshape a neighbourhood.

These so-called opportunity areas play a big role in where new developments pop up – there are 47 of them now identified across the city.

The idea is that by strategically putting resources into new construction, the government can help introduce new homes, jobs and investment into an area.

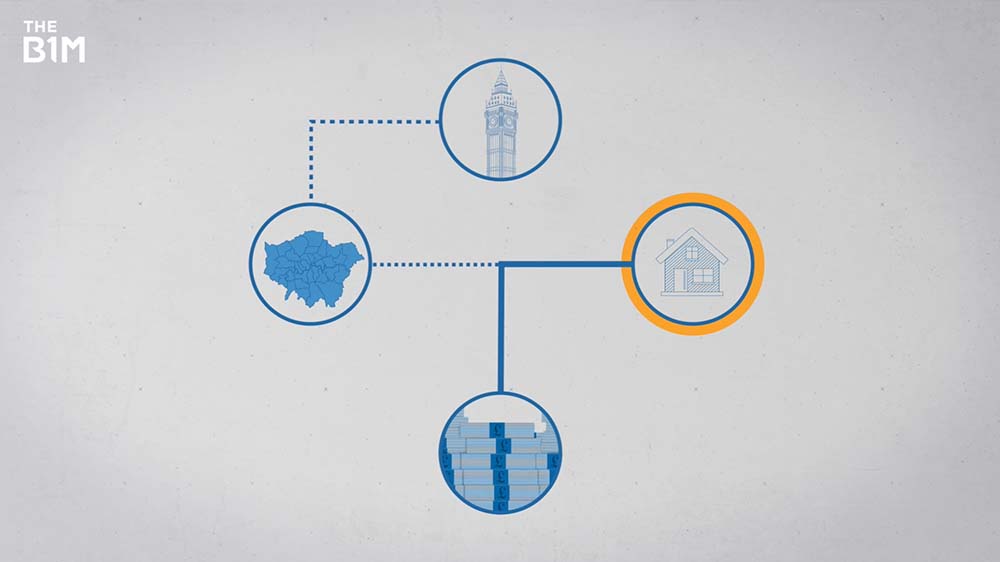

Above: The Mayor of London has identified 47 Opportunity Areas in various stages of development.

And that’s not just a London-thing. City planners around the world have long-used zoning rules and redevelopment programs to direct resources to certain regions.

San Francisco publishes its development pipeline, New York City has a map of urban renewal areas and Melbourne has a digital model of all its new developments.

Of course, every site is unique but if you want to get an idea of which neighbourhoods might soon be described as “up and coming,” maps like these are a really good place to start.

In theory, new homes, more businesses, public parks and better infrastructure like train lines are all good things. And so far, all the effort that’s gone into transforming Battersea is starting to pay off.

The neighbourhood has been topping lists of places to live. High-profile buyers like Sting and Bear Grylls have snapped up properties here – and despite slow sales at the start of the pandemic, the developers told us they’ve sold 94% of all residential properties.

House prices right across Battersea have more than tripled in the last twenty years. Now, the average is three-quarters of a million pounds. If you’re a real estate developer, local council or homeowner looking to sell some of your property to raise money – that’s good news.

But if you’re a Londoner looking for an affordable place to live, not so much.

A neighbourhood in transition

Battersea is still very much an area in transition. You can see the stark contrast just by crossing the road where you’ll find sprawling council housing estates that have stood there for decades.

Neil Pinder is working to make the architecture industry more accessible through his work as a teacher and non-profit HomeGrown +. He grew up in Patmore Estate and has seen firsthand how the area around the power station has changed over the last decade.

“I think in time it will change, because the more people that sell and the more people that buy in, it's a total change of demographics that's going to actually live in here,” Pinder said.

“And so that's how the whole neighbourhood will actually change. So you won’t probably recognise it in 20, 30 years.”

Above: Neil Pinder shows The B1M's Fred Mills where he grew up in Patmore Estate.

The fear is that it’s only a matter of time until these council estates – that now find themselves on high value sites in the centre of the city – are either demolished, or prices go up by so much that the current tenants can’t afford to stay or it makes more sense for them to sell their property and move elsewhere.

To be clear, there are no current plans to demolish Patmore Estate, but it wouldn’t be unprecedented.

Another South London neighbourhood called Elephant and Castle recently went through a similar regeneration. To make way for a new private development on a prime site, a massive public housing building was infamously demolished. Residents were uprooted from their homes and relocated.

Wandsworth – the London borough that Battersea Power Station sits in – has a higher level of homelessness than London on average. Despite a surge of new housing in the last decade, the number of people on the years-long public housing waitlist hasn’t gone down. In fact, it’s gone up.

Still, according to UK government data there are more than 87,000 empty homes across London – properties largely out of reach from the people that need them.

The struggle to build affordable housing

So why aren’t our governments just building more affordable housing?

Well, to put it simply, they don’t really have the money to do it. Local councils in London have been facing funding cuts for years, and their budgets are tight. Core funding to councils has been cut by 63% over the last decade. Meanwhile, the demand for housing has grown into a crisis, and they need to build a lot more homes.

They also find themselves in the possession of what are now extremely high-value areas of land in the heart of one of the world’s most desirable cities. Land that developers will happily pay big money for.

So, throw in the UK central government not giving them enough cash to build all the homes they need to, and councils have a high motive to turn elsewhere – and specifically to private developers.

Above: Councils are turning to private developers to fill gaps in affordable housing where government funding falls short.

Now London boroughs typically require between 30%-50% of new developments to be classed as affordable housing. But those rules aren’t written in stone.

And the definition of “affordable” in London isn’t as straightforward as you may think. For a while, it just meant social housing. But the government has changed the definition to include homes up to 80% of the market rent.

Aydin Dikerdem is a Labour councillor in Wandsworth. He’s a cabinet member, sits on the housing council, and has been an outspoken critic of the Vauxhall, Nine Elms, Battersea regeneration scheme.

“It's a watered down vision of what any kind of municipal project involving social housing would look like. The only kind of like crumbs that we're getting at the moment is this bit that we get from private development.”

The Battersea Power Station development promised to build some 600 affordable homes, or 15% of the total new units being constructed. But in 2017 that number was nearly cut in half to just 386 homes, or 9% of the total units – a move the developers put down to “technical issues”.

“I think you have to look at it in the wider context, because what we're delivering at Battersea is so much more than just affordable housing as our community offering,” Kinsey told The B1M.

“We work very closely with our local stakeholders in Wandsworth Council and when we looked at everything that we were putting forward, affordable housing was one element. A public realm was another element. The new infrastructure that we delivered with the tube, all of those commitments, you know, we we said if you look at everything holistically, we're delivering so much more than, I would say, the average developer. And, you know, in recognition of that, our affordable housing obligation was scaled back proportionately. But we do have an upside such that if we're able to deliver more in the future, we will.”

Now scaling back promises on affordable housing once a scheme has started isn’t unique to Battersea. It’s not uncommon for developers to secure the approvals needed to build, and to actually start construction, then cut some of the affordable housing for one reason or another.

It may be a breach of what was agreed, but most councils wouldn’t want to scupper the whole thing because of it. They’re often in a weaker position of influence than the developers.

“People often say, well, yeah, the developers are being greedy,” Paul Watt, professor of Urban Studies at Birkbeck, University of London, said.

“They're not being greedy, they're just doing what private developers do. You know, it's not the job of private developers to provide social housing. That's not their job. Their job is to provide income for their shareholders. That's what their job is. Private developers are not in the business of providing social housing because there's no profits in it.”

Above: A CGI rendering of the full Battersea Power Station Development. Image courtesy of Battersea Power Station Development Company.

The next chapter for our cities

We find ourselves at an extraordinary moment in history. Our societies suffer from huge wealth inequality. There’s unprecedented demand for affordable housing. Lots of new construction is happening. Large areas are being irreversibly transformed, and many apartments are sitting empty. As our city centres get more expensive, people will continue to move outward to more affordable areas and the culture will inevitably evolve as the next group of residents settle in.

Battersea Power Station is just one example of a new development that’s been constructed at this moment in time. And it's a potent reminder of the impact construction can have on both our cities' history and their futures.

On one hand, this development saved a formerly derelict heritage site and brought new life to what was once an abandoned wasteland in the form of a new park, shops and bars for the public.

But there are also less tangible impacts of this development, like how it will transform the local community over time. As some living in Wandsworth look around at all the new construction, they feel it’s not being made for them or their children.

This isn’t a dilemma that’s unique to Battersea or even London, it’s a global issue. If we want our urban areas to thrive, we’re going to have to build in a way that caters to everybody.

Video presented and narrated by Fred Mills. Special thanks to Battersea Power Station Development Company (BPSDC), Neil Pinder of HomeGrown +, Professor Paul Watt and Cllr Aydin Dikerdem.

Additional footage and imagery courtesy of BPSDC, The Guardian, BBC News, DW News, Virgin Media News, Fox 13, Channel 4, Marion Stokes, Katie Chan/CC BY-SA 3.0, Dancan Harris/CC BY 2.0 , ITV News, The Sunday Telegraph, Evening Standard, Thames News, Warner Bros. Pictures, CBS, CityNews, The Star, 7 News, The Dronalist, Foster + Partners, James Parsons Backdrop Productions, Charlie Round Turner, John Sturrock, David Rumsey Map Collection/CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, TM/CC BY 2.0, Zefrog, View Pictures, Jason Hawkes, Raph PH/CC BY 2.0, On Demand News, Wandsworth Council, ABC News, TheJournal.ie, 9 News, Sky News, Dave, PBS, KCAL9, The Project, Daily Record, Vice News, RTE, Peabody Sales, CBC News, Fox 29, MK Timelapse and CGP Grey/CC BY 2.0.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.