How a 23-Year-Old Solved Urban Sprawl

- Youtube Views 2,373,720 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotion for Epic Games.

WHAT IF our cities didn’t have to look the way they are now?

What if, instead of being crammed into giant vertical glass boxes we had terraces with gardens, air, open space and a real connection to nature?

And what if our skyscrapers soared diagonally instead? And what if they weren’t skyscrapers at all, but stacked villages with flying streets in between them and every amenity you could dream of just a short distance away?

This is Habitat 67 and it may be one of the most important building ideas of the 20th century. It reimagined urban living and inspired a generation of architects.

But in many respects it’s considered a failed dream and remains largely unfinished to its original design. Only a small portion of the original master plan was ever built.

That is, until now. Some 56 years later Habitat 67 is finally being completed. Just not in the way anyone thought.

Above: Habitat 67 as it stands today in Montreal, Canada.

Habitat 67 is a big deal. But this monumental piece of architecture had an unlikely start in life. It began as the thesis of a sixth-year architecture student, then took shape at the 1967 Montreal World’s Fair.

An audacious - and very young - Moshe Safdie submitted his designs to the World’s Fair when he was just 23 and apprenticing under American architect Louis Kahn.

“It began with a journey I made through North America to study housing,” Moshe Safdie told The B1M.

“I came to the conclusion that the suburban level towns were not they're not feasible in the long term, that they just consume too much land, too much energy, too much transportation. We have to bring people back to the city. But people prefer houses. That's why they're in the suburbs. Therefore, if we could reinvent the apartment building so that it gives you the quality of life of a house, a garden, privacy, access through an open street, people will be more willing to live in cities.”

Now, it’s typical for World’s Fair expos to build entirely new structures to host the event. Other expos before them had built towering monuments and gimmick structures that would be taken down soon after, but Canada wanted to construct something substantial. Something that would make us rethink the way we lived.

They found it in Habitat 67. It would be a pilot program for a whole new type of housing: one that wouldn’t contribute to sprawl or be just another soulless tower.

To really understand why this was so groundbreaking, we have to put ourselves in the 1960s.

1961

Two very important things were happening in urban planning at this time. The first was zoning. We began dividing our cities up, separating them into their functions.

“Residential in one part of the city offices and employment in another part of the city industry in another part of the city,” Safdie explained, “all separated because the concept was you shouldn't mix different land uses in one place.”

The problem is, people’s lives aren’t divided as cleanly as that. Part of the reason why zoning came to popularity was because of the car. Suddenly it was possible to separate out these places by vast distances.

But then we’re designing our cities for cars, and not for people.

Habitat 67 does away with this idea. Instead, it puts everything in the same place. It was one of the first truly mixed-use developments. Words we now see describe almost every major new construction project today.

“A mixed use development is one which takes all the ingredients of urban life and builds them into a single structure or accommodation within the structure,” Safdie said.

“So in its simplest form, it's a shopping centre with towers of residential and art and offices and other facilities. But in its most sublime form, it's residences with all the things that a community needs, like schools and shops around them, plus places for work offices, workshops, etc. integrated into a singular development.”

Above: A drawing of Habitat 67 from 1961.

This folded into utopian ideas for architecture that started to emerge in this time following the post-war period. Everything was being rethought and anything could be possible.

So Canada took a chance on a 23-year-old freshly graduated architect and his bold idea.

At the core of Safdie’s vision was pre-fabrication. Apartments made in factories, assembled module-by-module on site.

As he developed Habitat 67 he came up with the concept of a “hillside”. Safdie’s original thesis had the modules stacked twenty to thirty storeys high in a frame-like tower structure but he realised if he leaned them back as if they were on a hillside they could have gardens and other areas open to the sky.

The “hillsides” would hover over sheltered public spaces on the ground below and would be laced with “streets” every four floors for access.

But Safdie and his team were unable to secure the $45M in funding. Instead the government gave them a budget of just $15M.

“My first reaction was, go to hell it’s everything or nothing. And then I started rationalizing…” Safdie said.

“And so it took 24 hours to have me go through the full cycle saying, I can't miss that opportunity. It wouldn’t be the ideal. Do what you can without budget, which led to the habitat that we built, which is not the membranes. It's kind of more of a village, an urban village.”

Instead of a community for 1,200 families rising 30 storeys in the air, Safdie’s Habitat was scaled back to just 158 residences across three pyramids less than half the original height.

“It didn't make it different. It didn't reduce the quality of life within your apartment, you still had your gardens, you still not your open streets, but by scaling it down, it became more of a building than a community.”

1963

It’s now 1963 and we’re still decades away from computer-assisted technology. 3D printers are more than half a century off and this immensely complicated design had to be developed entirely by hand through sketches and models. So many, many models.

The work was labour-intensive and the days were long. At its peak Safdie was spending up to 14 hours in his studio at a time.

Then, something amazing happened. The invention of LEGO.

The Habitat design team bought nearly every LEGO set in Montreal when the little plastic bricks arrived in North America.

“Lego was a block, but it was modular and it had the capacity to connect, but it had the discipline,” Safdie said. “There was a system to it. You could connect it through the clicking so it could be stacked or 90 degrees or in parallel shifted by increments. And it was working with that system that I designed Habitat with Legos.”

Above: Habitat 67 was designed as though each unit was on a hillside, with space for a terrace.

Turning these blocks into reality required an engineer of immense skill. To find one, Safdie ended up poaching the engineer from his former boss, architect Louis Kahn.

He had his work cut out for him. It promised to be one of the most challenging construction projects of the decade and the pyramid structures with gaping holes underneath them worried many traditionalists.

In fact both McGill University and the University of Toronto produced a report stating that if Habitat was built as designed, it would collapse – and if it didn’t collapse on its own, then it would probably be brought down by an earthquake.

Safdie and his engineer had to convince the city of Montreal that they knew what they were doing.

When the first module was lifted into place Safdie’s wife christened it with a champagne bottle, as though it were the maiden voyage of a grand ship.

Before the buildings were even finished they started stoking controversy. In 1965 critics called for a Royal Commission to investigate why something so foolish was being built.

In 1966 a new minister wanted their funding stripped and the units dumped into the Saint Lawrence River, but the project was already too far along.

There were labour shortages too and the construction team had to rush to get everything ready for Expo 67. In the end one-third of the interiors were left unfinished, to be completed at a later date.

Slowly but surely each module was cast in a factory operated on site, then lifted into place by crane. Safdie was proving to the world that prefabricated housing could work.

1967

The day of the Expo arrived. More than 50M people descended on the Canadian city throughout the duration of the World’s Fair, a record that has not been beaten.

Safdie moved into one of the apartments with his wife and two children and lived there throughout the duration of the fair.

By all accounts Habitat 67 was a triumph and suddenly Safdie became what we would now call a starchitect. Offers from all over the world came in to visit and lecture. He had set the architectural world on fire.

“Well, in that respect, it's like living happily ever after because habitat is a vital, successful and very desirable community,” Safdie explained. “And the fact that people stayed there for decades, the fact that in many cases, the second generation and even third generation lived there, that it has the longest occupancy of any building in town. And that shows that people love it, they want to be there.”

Above: Habitat 67 under construction in the 1960s.

But as the decades passed the legacy of Habitat 67, while inspiring awe, was that of an unfulfilled dream.

The architectural revolution it promised never came.

It’s these buildings that embody the two greatest words of the human imagination. Two words that when uttered correctly have shifted the course of civilizations, have created movements and opened minds: What if?

A very young and emboldened Safdie dared to stand against the establishment and ask just that. These buildings still ask it to this day.

And today’s architects and designers are doing the same. What if Habitat 67 had been completed to its original design? Would this dream of housing be available to everyone? Could it still be?

Neoscape approached Safdie Architects about modelling Habitat 67 digitally, to preserve and share the design with the world.

It was Safdie Architects that then proposed completing the development virtually, but all of it this time.

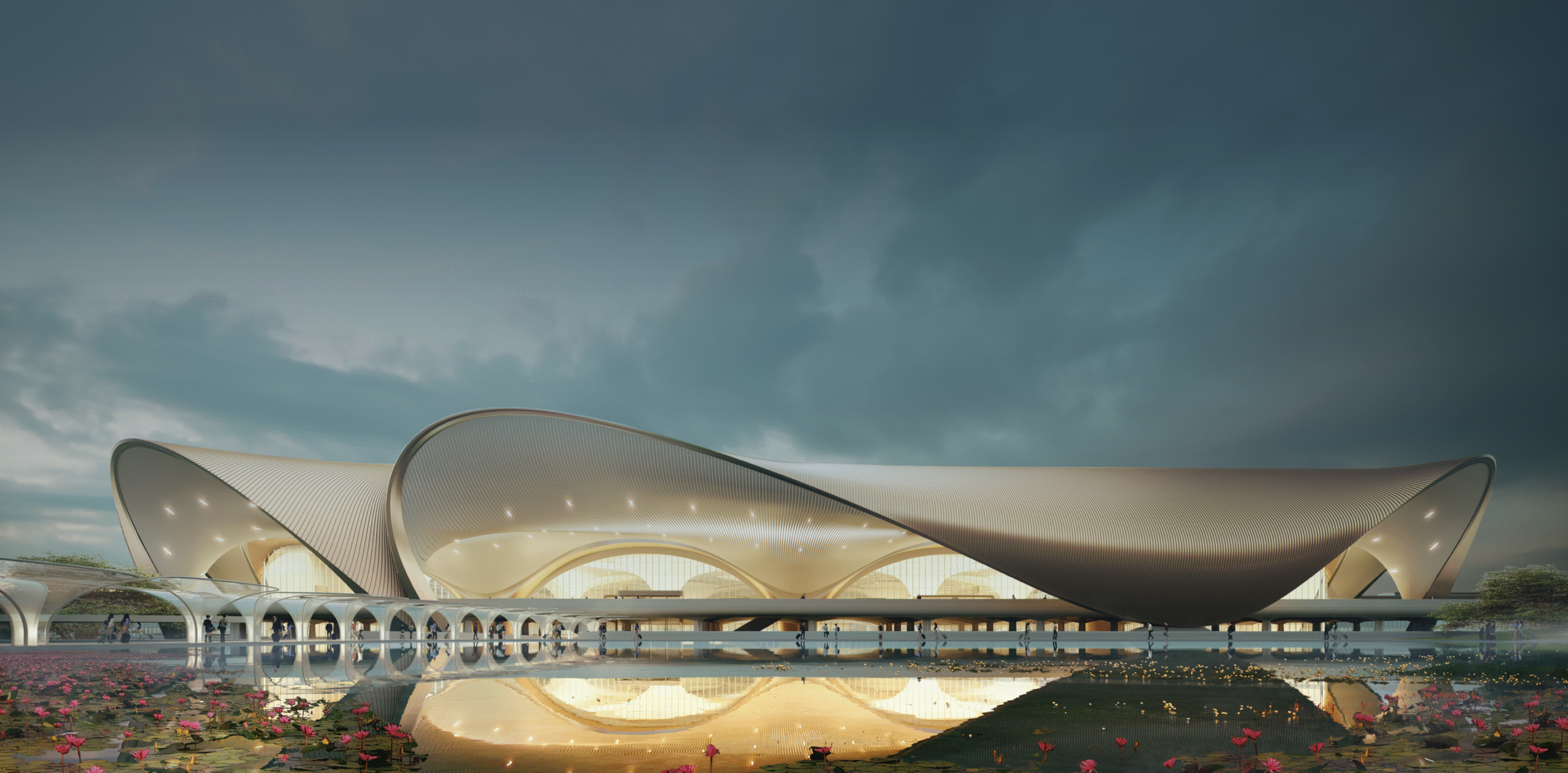

Above: Habitat 67 as realised by Epic Games and Neoscape.

Using Epic Games' Unreal Engine, technology Safdie could have only imagined back in the 60s, this could now actually be done.

“I kept going back to those ideas Habitat was built on. I also knew that Habitat was never built like it was designed to be built,” Carlos Cristerna, Senior Product Specialist at Epic Games said.

“When Epic came to us with the challenge of bringing Habitat 67 to life, we were super excited. You know, it was a project that is important in the architectural world,” Ryan Cohen, Principal at Neoscape added.

The team worked with Safdie to complete the original masterplan. This included the enormous 30 storey A-framed towers that leaned back from the riverbank.

“Working with Safdie on this project in particular was interesting because it was really working on a design that was thought as a concept 50 plus years ago,” Cohen said.

“When Neoscape and Epic came to us and said, 'What about the original habitat?' I was very excited because I've never actually experienced three dimensionally what it's like,” Safdie said. “And so it's always been a question in my mind, what would it be like if we really had those $45 million? How would it have been as a community? Are they hidden issues that we didn't realise?

“It was an immediate reaction [when I saw the finished model]. I would love to live there, and that's the ultimate test. And yet at the same time, I realised boy was ahead of its time. It's ahead of its time today.

“I hope that actually making this accessible to the public at large as an image, as an idea you could live like that would now help advance people's desire to have this realised."

This model has been painstakingly created by those who are passionate about Safdie’s vision – just like his original physical models in the 60s.

“What if” are tantalising words. They can shift mountains, hillsides. Safdie’s ideas have returned to the architectural zeitgeist. A new generation is discovering them and instead of letting them rest on the banks of the Saint Lawerence River, they want to do something with them.

You can see the model in Unreal Engine for yourself, and find out how this generation of architects worked with Sadie to fully realise his vision here.

Video hosted by Fred Mills. Special thanks to Epic Games, Neoscape, Inc., Safdie Architects, Matias-Garabedian, Trofar, CBS Sunday Morning, TED, Spirit of Space, Discover Montreal, QHD Habitat, Toto, Paramount Pictures, 20th Century Fox, United Artists, Tom Parnell, Jean-Etienne Minh-Duy Poirrier, Bellisario, Lego, University of Toronto, If Walls Could Speak by Moshe Safdie, Universal Pictures, Warner Bros. and Vertigo Films.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.