How the global construction industry faced 2020

THE reverberations of 2020 will be felt for years to come. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic fallout upended nearly every aspect of modern life - and the global construction industry was no exception.

While we're not yet far enough away from these events to completely understand their full impact, we can see that the industry as a whole generally responded with resilience.

Governments around the world invested in massive and unprecedented infrastructure projects, developers fast tracked major proposals, and construction sites found ways to adapt to shifting safety guidelines and unpredictable supply chains.

Despite this agility, the cost of COVID-19 was still very real; the US industry effectively lost two years of GDP gains and four years of job gains.

In the UK, industry growth and decline roughly followed the country’s national and local lockdowns. April saw a record decline in construction output, while August saw record growth.

While we're not out of the woods, the rollout of vaccines and the promise of economic recovery is beginning to signal that we may be through the worst of it.

Here we look back at a year unlike any other.

GO BIG OR GO HOME

Once the economic implications of widespread international lockdowns became clear, governments all over the world began accelerating major construction projects in a bid to counter looming recessions.

China, well versed in epidemics, swiftly began pouring money into massive infrastructure projects.

Mid-way through 2020, the country announced its high-speed rail network would double in size over the next fifteen years. The People’s Republic hoped the new rail scheme would stimulate demand and redistribute economic prosperity away from the coastal cities and into the country's struggling interior - where nominal per capita income is far lower.

If the project succeeds, then by 2035 all Chinese cities with a population of more than 200,000 people will be connected by rail and all cities with more than half a million people will have access to high-speed rail.

Similarly, the French government announced a USD $122BN investment into the country’s infrastructure following a predicted 11 percent fall in national output for 2020.

The bulk of the money went towards building retrofits and railways, while around USD $36BN was reserved for sustainable energy and transport.

Meanwhile, the UK invested $800BN into infrastructure projects; including the construction and upgrade of schools, roads, courts and hospitals.

Australian state governments began rapidly approving major projects as well. By July the New South Wales government had approved 19 state-significant projects collectively worth USD $4.7BN.

The Victorian government approved the 101-storey, 356-metre high Green Spine tower in Melbourne, set to become the southern hemisphere’s tallest building. According to the skyscraper’s developers the project has now officially started construction.

Melbourne will also shortly begin work on what will be the largest infrastructure project in Australian history: the 90km long "Suburban Rail Loop".

The scheme is projected to create 800 direct jobs and at the peak of its construction support more than 20,000 jobs.

While most macroeconomists argue for investing in infrastructure following (or during) a hard recession, the US largely failed to do so in 2020.

This may change in 2021, considering president-elect Joe Biden made building sustainable infrastructure a campaign promise.

THE COST OF COVID

COVID-19 hit the US construction industry especially hard. A survey of contractors conducted by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) in November found that more construction projects had been cancelled than started in 2020.

Unlike the UK, which witnessed periods of setback and growth zig zag throughout the year, the US mainly grappled with decline.

The study found that 32 percent of contractors had a project cancelled or postponed in June. That number increased to 60 percent in August, then more than 75 percent in November.

The pandemic also created a shortage of construction materials and equipment as well as available craftworkers and subcontractors.

Overall, construction employment fell by 65 percent across 234 metro areas in the US between September 2019 and September 2020.

Houston, Texas lost the most jobs at 24,400, followed by New York City, which lost 19,500 jobs.

POST-PANDEMIC OPPORTUNITY

While we assess the damage wrought by 2020, there are already those looking to the future, with architecture studio Hassell preemptively dubbing 2021 as “the year of the experiment”.

It's an understatement to say 2020 changed everything.

From the way we travel, to where we work, how we get food, how we socialise, how we go on dates and how much TV we watch, almost every aspect of our lives has been thrown up in the air, and the built environment will have to catch up.

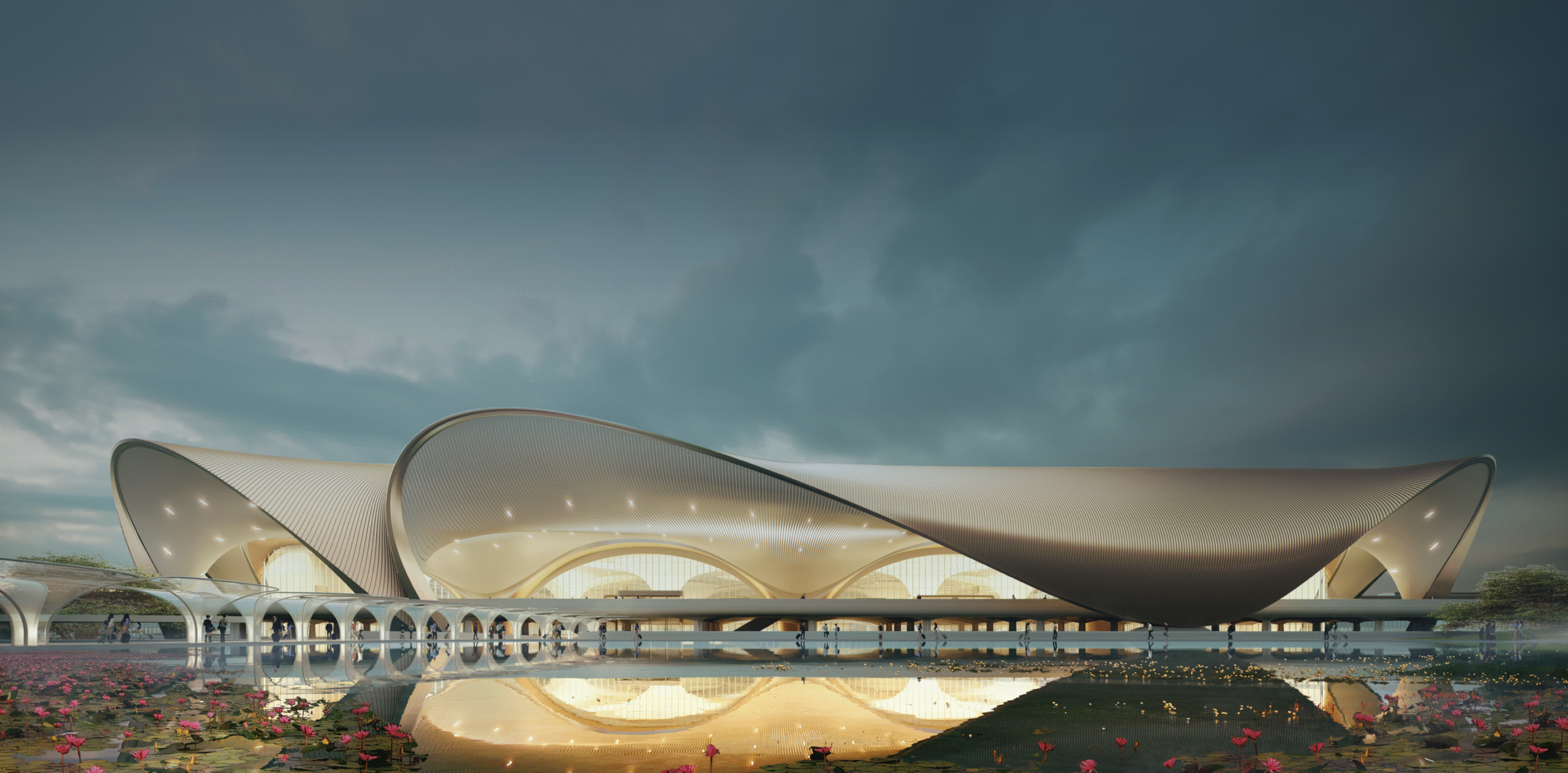

Will the way we feel about high density living change? What will airports look like? Will public transport have to be rethought? And, perhaps the most pressing question after almost a year of working from home, will people go back to the workplace?

Hassell has taken Australia as a case study to examine what the future of the workplace will be.

Australia as a whole is already starting to recover from the pandemic, with many parts of the country having gone more than a hundred days without a case. A degree of normality is starting to settle back in.

Hassell found that while people are beginning to return to the office, many now prefer to work from home. We may be entering a new age of flexibility where both options are possible and the typical workplace will be replaced with a stripped back central office. Large scale commercial spaces may become a thing of the past.

This way of thinking will undoubtedly carry over to other aspects of design and construction too. In the same way the cholera outbreak in the 1850s gave us modern sewage systems and ushered in a new architectural age for London, COVID-19 may be the impetus for dramatic changes in our modern urban landscapes.

The world post-pandemic, whatever it holds, is only just beginning.