How Spain Built the World’s Most Complex Building

- Youtube Views 616 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. This video contains paid promotion for CATIA.

In the early 1990s, Bilbao was in trouble. A city built on steel, shipbuilding and heavy industry was reeling from economic decline, its docks silent and factories shuttered. Unemployment was high. Morale was low. And in this context, the local government proposed something extraordinary: to revive the city’s fortunes by building an art museum.

Not just any museum — a radical new structure that looked more like a sculpture than a building. With swooping titanium walls and impossible curves, many said it couldn’t be built. Others said it shouldn’t.

Above: The Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao.

But they built it. And it changed everything.

Today, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is one of the most recognisable buildings in the world. But behind its striking façade lies a story of bold ambition, improbable engineering, fighter jet software, and a titanium-clad gamble that would redefine a city — and an industry.

The Basque Country in northern Spain was once the industrial powerhouse of the nation. For decades, Bilbao had thrived as a centre of steelmaking, shipping and manufacturing. By the 1970s, however, global competition and shifting economic forces brought that era to a close.

Above: Bilbao in the 1970s. Image courtesy of Eusko Jaurlaritza-Gobierno Vasco, Euskadiko Artxibo Historikoa / Archivo Histórico de Euskadi.

Between 1979 and 1985 alone, a quarter of the city’s industrial jobs disappeared. The river Nervión, once lined with busy shipyards and furnaces, became a symbol of post-industrial decay. By 1991, as the Cold War ended and Spain adjusted to its role in a newly integrated Europe, Bilbao faced an uncertain future.

Juan Ignacio Vidarte, Director General of the Guggenheim Bilbao from 1997-2025, remembers it clearly. “The city was undergoing a fairly fundamental crisis,” he says. “It had been wealthy for a hundred years, but suddenly that was gone.”

It was in this moment — of both crisis and transition — that the Basque Government proposed a new direction. The future, they believed, lay not in coal and steel, but in culture.

Their vision was ambitious: to turn Bilbao into a cultural and tourist destination by launching a sweeping programme of infrastructure and landmark projects. The city commissioned Norman Foster to design a new metro, Santiago Calatrava to build a pedestrian bridge and an airport terminal — and most controversially, it partnered with New York’s Guggenheim Foundation to build a world-class museum of modern art.

Above: The Bilbao Metro

The regional government agreed to fund the $100 million cost of the building, plus a one-off licensing fee to the Guggenheim Foundation in exchange for use of the name and access to its collection. At a time when unemployment hovered around 20%, the move sparked a fierce backlash.

“The project was very controversial from the beginning,” says Vidarte. “There was a lot of resistance to the idea of spending public money on culture instead of basic needs.”

Nevertheless, a design competition was held. And among the submissions, one stood out.

Frank Gehry’s proposal didn’t look like any museum the world had seen. It defied the geometry of traditional buildings, swapping right angles and straight lines for flowing, organic forms that seemed to melt and shimmer in space.

Above: Frank Gehry's concept sketches for the museum. Image courtesy of Gehry Partners, LLP.

Gehry, already known for his unconventional designs, had faced serious challenges with previous projects — most notably the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, which had stalled due to funding and engineering problems.

Choosing him for the Bilbao commission was a risk. But the selection panel felt his vision best matched the ambition of the city’s transformation.

And this time, he had a secret weapon.

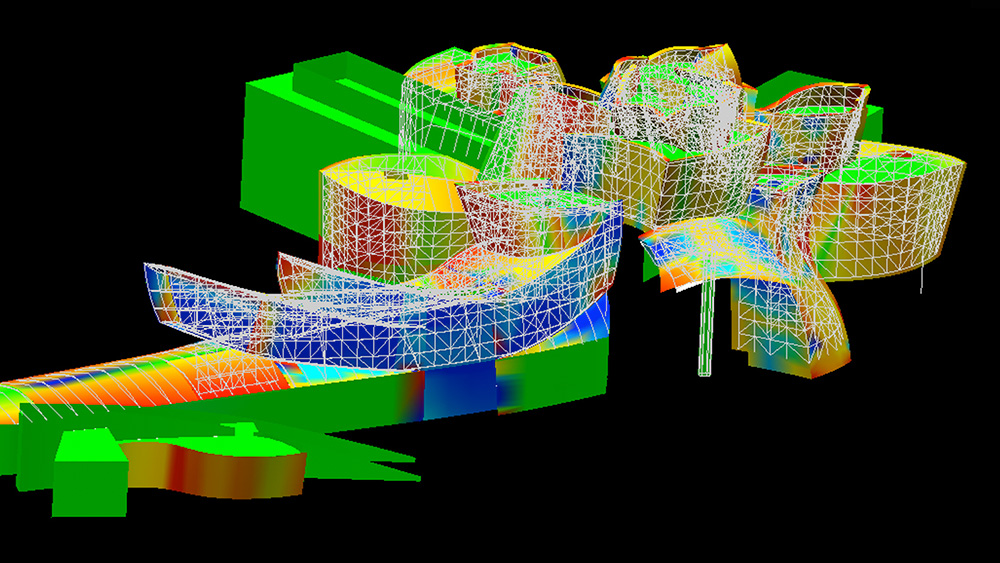

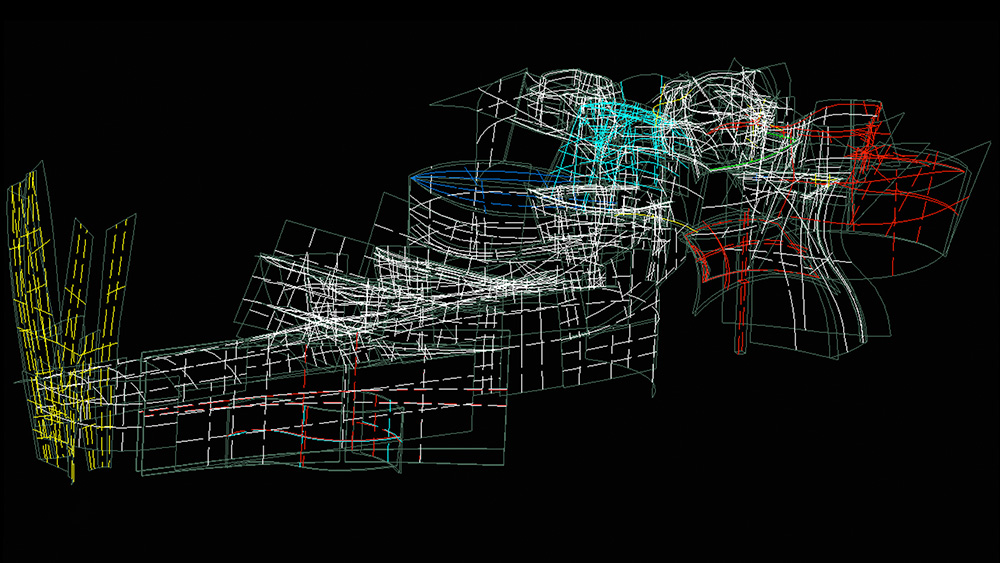

To translate Gehry’s wildly complex shapes into a buildable structure, his team turned to a surprising source: CATIA, a 3D modelling software originally developed to design military aircraft.

At the time, most architects used rudimentary computer-aided design (CAD) tools, which could model only in two dimensions or simple three-dimensional blocks. CATIA, by contrast, allowed Gehry’s team to model highly intricate curves using mathematical precision — a process known as non-Euclidean geometry.

Above: A CATIA model of the Guggenheim Museum, bilbao. Image courtesy of Gehry Partners, LLP.

“It was revolutionary,” says Dennis Shelden, who worked on Gehry’s team. “You could visualise a complex shape from every angle, and generate instructions from that model to guide engineering and fabrication.”

The software had been used to develop the Mirage fighter jet and was playing a key role in Boeing’s design of the 777, the world’s first fully digital aircraft. Now it was being used to model a building.

From hand sketches to paper models to digital simulations, Gehry’s team developed the Guggenheim’s design in a way no architectural project had been realised before. CATIA didn’t just describe the shape — it broke it down into thousands of parts, each of which could be manufactured and assembled with millimetre precision.

Above: A CATIA model of the Guggenheim Museum, bilbao. Image courtesy of Gehry Partners, LLP.

It also helped solve another puzzle: how to construct curved surfaces using flat materials. CATIA could “unfold” the building’s skin, providing 2D templates for each titanium panel — a task that would have taken teams of engineers weeks to complete by hand.

Titanium wasn’t the original choice for cladding. Gehry had used lead-copper alloy on earlier buildings, but environmental concerns ruled it out. Stainless steel, another contender, didn’t reflect light in the way he wanted.

Then, by chance, Gehry noticed a piece of titanium outside his Los Angeles studio on a cloudy day. The way it captured the grey sky reminded him of Bilbao.

But titanium is notoriously expensive — more commonly used in aircraft than architecture. Fortunately, a geopolitical twist changed the equation. In the early 1990s, the Soviet Union collapsed, and with it came the dismantling of Alfa-class nuclear submarines. Their titanium hulls were sold off, flooding the market and pushing prices down.

Above: A Soviet Alpha Class submarine.

Suddenly, the once-exotic metal became a viable option. The Guggenheim would be clad in 33,000 paper-thin panels of titanium, each measuring just 80 by 115 cm and precisely shaped to match the building’s complex curves.

Construction began in 1993. Gehry’s team in California continued refining the digital models, while engineers in Chicago and builders in Bilbao raced to turn data into reality.

Though CATIA provided exact specifications, it didn’t dictate how to actually build the structure. That challenge fell to engineers like Juan Ramon Perez Gonzalez.

“What is CATIA for us?” he says. “Perfectly designed surfaces. But not ready to build.”

Above: The Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao under construction. Image courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao.

The solution involved layering structures: a rigid steel skeleton beneath, a secondary frame of curved beams on top, and finally a tertiary mesh to create the double-curved surfaces. No two steel beams were identical. Some parts had to be held in place by cranes until the structure was complete.

Even installing the cladding was difficult. Cranes couldn’t reach every surface, so the team brought in professional rock climbers to scale the building and fix the panels by hand.

As the museum took shape, local scepticism slowly gave way to intrigue. By the time it opened in October 1997, public sentiment had turned.

Below: The Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao.

“The first year, everybody was shocked,” remembers Perez Gonzalez. “But little by little, people fell in love with the project.”

And it worked. The museum drew 1.3 million visitors in its first year — more than triple expectations. CNN covered the opening. International tourists arrived in droves. The local economy boomed.

Infrastructure projects followed: the new metro, footbridges, an airport terminal. By 2000, Bilbao’s transformation was in full swing.

The Guggenheim Bilbao became a global benchmark for urban regeneration. Its success inspired a wave of museum-led revitalisation efforts — from the Tate Modern in London to the Pompidou Centre in Metz.

Above: The Tate Modern, London.

But replicating Bilbao has proven difficult.

“The idea that you can solve a city’s problems by inviting a star architect to build a flamboyant building — that’s fundamentally wrong,” warns Vidarte. “It only works when part of a wider strategy.”

Indeed, the Guggenheim was just one element in a broader plan that included transport, housing, environment, and long-term investment. What made it special was how everything aligned: the moment, the need, the vision, the execution.

The project’s impact extended beyond Bilbao. It helped usher in the use of Building Information Modelling (BIM), reshaped the relationship between architects and engineers, and transformed how complex structures are designed and delivered.

Gehry went on to launch Gehry Technologies, which brought digital design to a global audience. His once-troubled Walt Disney Concert Hall was revived using the same methods and opened in 2003 to acclaim.

Above: The Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles.

Today, the Guggenheim Bilbao remains a symbol of transformation — not just for a city, but for an entire profession.

As visitors walk its gleaming curves along the riverfront, few realise the building’s design helped launch a new era in architecture. Fewer still may know that it only happened thanks to a fighter jet software programme, a piece of titanium on a cloudy day, and the dismantling of Soviet submarines.

But perhaps that’s fitting. Because the story of the Guggenheim is, at heart, a story of seeing possibility where others saw only problems — and of building something beautiful in the most unlikely of places.

Additional footage and images courtesy of Gehry Partners, LLP, ENRIC, ISIWAL, BIOSJERBIL, MTV, CNN, MGM, DW NEWS, BBC, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Sydney Pollack, CYGNUSLOOP99, 20th Century Studios, PBS, CBS, Eusko Jaurlaritza-Gobierno Vasco, Euskadiko Artxibo Historikoa / Archivo Histórico de Euskadi, Zinneke, Ministry of the Presidency, Government of Spain, Nigel Young, Foster + Partners, Richard Davies, Wilson Centre, Basotxerri, Andres Rueda, Aitor Ortiz for the Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, Ferrovial, Ultan Guilfoyle, Olivier Boissiere.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.