HS2: The £100BN Railway Dividing a Nation

- Youtube Views 5,235,690 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

CONSTRUCTION projects don’t come much bigger than High Speed 2 (HS2). It’s a new super-fast railway being built right up the heart of Britain with the promise of economic growth, low-carbon travel, more capacity and some of the fastest trains on Earth.

But building it is far from easy. The project has gone several times over budget, faced delays and staunch opposition.

HS2 is now known more for its setbacks and the decisions of those in power than its benefits and the incredible engineering going into it. An idea to bring a country closer together has become divisive.

.jpg?updated=1660033045750)

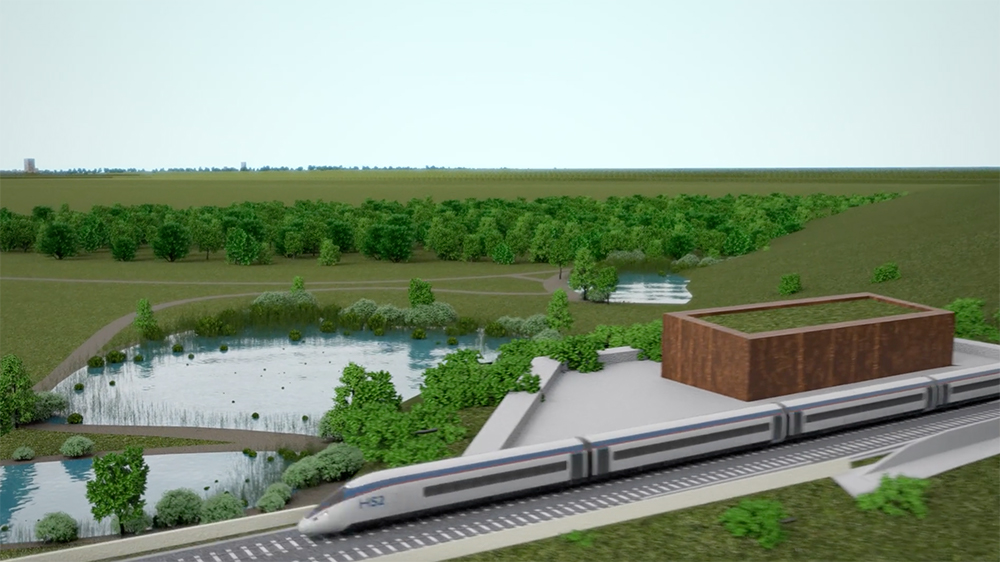

Above: HS2 is one of the world’s biggest infrastructure projects. Image courtesy of HS2.

And yet it’s not just a UK issue; we’re seeing this everywhere. When public money is involved the stakes get much higher, the scrutiny gets more intense, and when things go wrong it can become difficult, or even impossible, to stop.

So how much say do we really have over massive projects like HS2 built with our money? Can our governments ever stop once they’ve started? And is there a point at which these schemes are no longer worth it?

Connecting a country

Like many countries, the UK is divided. There are big economic and social differences between the capital and the rest of the country with little sign of anything changing.

Back in 2009, the government proposed a new high-speed railway to better connect London and the North of England, spreading wealth up the country. Three years later, that project was approved and billions of taxpayer cash was set aside.

HS2 is being built in three stages. Phase 1 runs from London to Birmingham, Phase 2a will carry the route to a town called Crewe and 2b takes it to the cities of Manchester and – originally – Leeds.

High-speed trains would then continue on to other parts of the country at normal speeds using the existing network, so those living in the wider North and Scotland can benefit too.

Trains will have a top speed of 225mph – the fastest in Europe. But to do that they need a track that’s as straight and flat as possible, and drawing a straight, flat line up the middle of England isn’t easy.

Some 90% of the Phase 1 route will be up on bridges and viaducts, or dug below ground in tunnels and cuttings, making it less visible. It’s an immense feat of engineering.

The route in detail

A journey North from London will begin at a new three-storey terminal in Euston. It’ll have the UK’s largest concourse; a prefabricated geometric roof and ten platforms built some eight metres below ground.

After Euston, trains will arrive at Old Oak Common, where there will be additional links to Heathrow Airport, Wales and the Southwest.

The first landmark outside London is the Colne Valley Viaduct, set to become the country’s longest railway crossing. It’s 3.4-kilometres long and runs over several waterways.

Next up is the 16-kilometre Chiltern Tunnel – the longest and deepest on the entire route, sitting up to 90 metres underground. Then it’s another tunnel, but this one is less about length and depth, and more about what’s above it.

.jpg?updated=1660033522382)

Above: A tunnel boring machine being prepared at the Long Itchington Wood site. Image courtesy of HS2.

The UK has over 300,000 hectares of ancient woodland – that’s trees that have been around since 1600 or before. Despite weathering the ages, some of those trees now find themselves in the path of HS2.

Instead of cutting them all down, planners have tried to limit their destruction and one way is to go underneath them, like at Long Itchington Wood.

To make this possible, construction teams are using 2,000-tonne tunnel boring machines (TBMs) to cut a path.

TBMs feature a cutting head at the front and a system that quickly takes soil away back up to the surface in pipes along the sides of the tunnel.

.jpg?updated=1660033635900)

Above: HS2’s TBMs weigh 2,000 tonnes. Image courtesy of Herrenknecht/BBV/HS2.

The Long Itchington tunnel will run for 1.6 kilometres and be the first to complete across the whole route when it finishes in 2023.

The last stop before Birmingham is the Solihull Interchange, currently billed as the “world’s most eco-friendly railway station,” with connections to the airport and exhibition centre.

Phase 1 culminates at Birmingham Curzon Street – the first inter-city rail terminus built in the UK since the 1800s, with an arched roof inspired by the railway pioneers of that era.

It’s all a lot of work and money to connect London and the Midlands, but there’s a pay-off: economic growth.

The benefits of high-speed rail

The idea is that the billions being poured into this project will be paid back, and that millions of people will have their quality of life improved.

High speed rail effectively brings major cities and population centres closer together. Businesses can access larger customer bases, supply chains and labour pools. Integration and trade are improved, productivity goes up and commuting longer distances becomes possible – you no longer have to buy a house in an expensive region in order to work there, and that takes some of the pressure off the housing crisis.

HS2 will slash journey times, too. Getting from London to Birmingham will take just 45 minutes – 37 minutes quicker than today. But better connectivity between regions is about more than just speed. There’s another key word in all of this: capacity.

If you look at the UK’s rail map you might question whether this project makes any sense. London already has a direct connection to Birmingham and Manchester via the West Coast Main Line – so why build another?

Above: A map showing existing rail connections from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds.

Because it’s one of the busiest railways in Europe, used by inter-city, local and freight trains all at the same time, and things can get crowded.

HS2 will be just for high-speed passenger trains. It’ll mean getting up and down the country quicker and free up much-needed space on the existing lines.

The hope is that this will all make taking the train an obvious choice as compared to driving or taking a domestic flight, bringing carbon emissions down. It’s designed to be the world’s most sustainable high-speed railway.

Above: HS2 promises zero-carbon travel from the day the trains start running. Image courtesy of HS2.

It all seems like a good idea, but there are some who question whether the UK actually needs this high-speed line at all.

Unlike some other countries renowned for their high-speed rail networks the UK’s major cities are all much closer together. That’s a factor that has perpetuated the lack of an extensive high-speed network in the UK to date and one reason why it hasn’t cultivated much homegrown expertise good at building it.

The guy tasked with leading the team that’s having a go for the first time in decades is HS2 chief executive Mark Thurston.

Above: Mark Thurston has been in charge at HS2 Ltd since 2017.

“HS2 is a once-in-a-generation project, which will connect all the major cities on that corridor at high speed, clearly making a massive difference to the way we decarbonise our transport system,” Thurston told The B1M in an interview.

“It is unprecedented - over 300 sites just between here and the West Midlands. But also, if you look around us here in Euston, we're right on top of the local community. So how do we build this railway sensitively in a way that respects people who have got to get on with their lives, for some years yet, until this project is fully commissioned?”

Who makes the decisions?

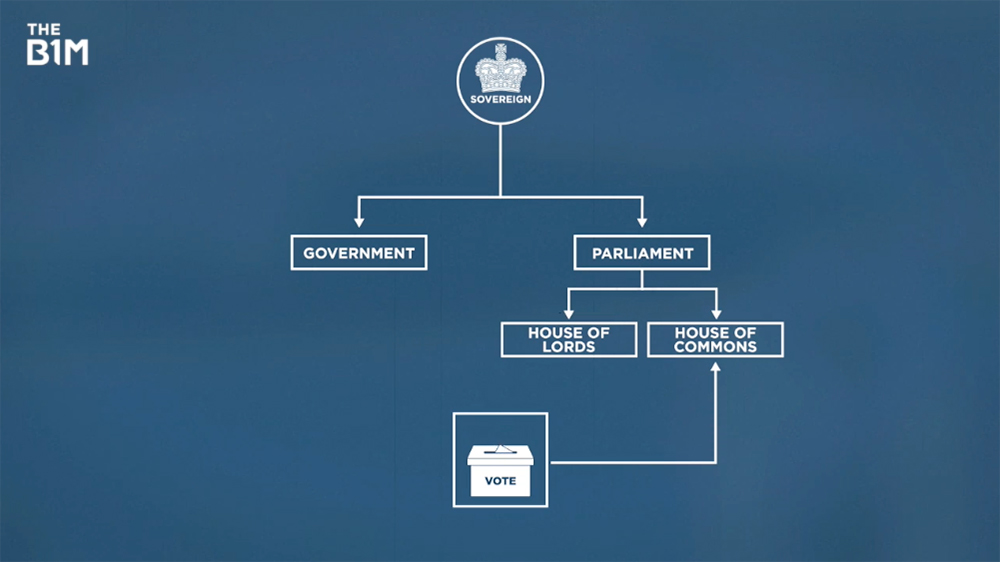

The UK is a constitutional monarchy. The sovereign delegates power to a democratically elected government and lower house of parliament called the House of Commons.

Above: The UK’s political system.

Like many countries, we elect people from each region to sit on parliament and represent us. The political party that wins the most seats forms the government. They get to control all the government departments and decide which laws are introduced and debated in the House of Commons. They pretty much set the agenda.

We decide which candidate or party we’re going to vote for based on what they say they’re going to do and in the UK the two major parties – the Conservatives and Labour – both advocate the principle of a new high-speed rail line. So, in a way, the people chose this.

THE KEY DATES

The elected UK government formally decided to build HS2 back in 2012. After a lot of debate and consultation, finally in 2017 parliament overwhelmingly passed a b ill giving the government special powers to build, operate and maintain Phase 1.

When Boris Johnson then became prime minister in July 2019, he commissioned the Oakervee Review to advise his government on whether and how to proceed.

With powers already obtained from parliament back in 2017, Boris signed the Final Notice to Proceed with the project in 2020. Permission for Phase 2a followed in 2021.

To try and get a better understanding of this complicated system and how it’s used to approve projects like HS2, The B1M went to see Stephen Glaister. He’s Emeritus Professor of Transport and Infrastructure at Imperial College London and was a contributor to the Oakervee Review.

Above: (L-R) Stephen Glaister talking to The B1M’s Fred Mills.

“The parliamentary process is very important to a big scheme like this. You can't build a railway in this country without parliamentary approval,” Glaister said. “And the point about the debate in Parliament - and this applies for a lot of big public infrastructure projects - is the government has made a decision in principle to build this scheme.

“So, it’s a matter of policy to build the whole scheme. The parliamentary process is to allow people who are badly affected to make their case about how their interests should be dealt with.”

The funding

In 2012 when the project was first backed, it was given a target finish date of 2026 for Phase 1 and 2033 for Phase 2. The initial budget was set at £32.7BN – that’s a lot of cash.

It’s funded by something called a “grant-in-aid” from the government, which in turn gets its money from the tax-paying public.

Small amounts gathered from millions of people can create a hefty budget, and that’s what puts most national infrastructure projects in a completely different budget galaxy to skyscrapers or other buildings funded by private companies or individuals.

Even tech giants like Google, Facebook or Apple don’t spend more than a few single-digit billions on their flagship projects, and they’re some of the richest firms in the world.

.jpg?updated=1660034403803)

Above: Google’s new Bay View campus. Image courtesy of Iwan Baan/Google.

You would think that combining such a budget with the UK’s history as the birthplace of rail would be a winning formula. But HS2 hasn’t gone to plan and public opinion now is generally far from positive.

Data from May 2022 shows that only 7% of Brits strongly support HS2, compared to 19% that strongly oppose it.

What changed?

So, what happened between the original business case - when all those benefits made it sound like a no-brainer – and today?

Many are unhappy with the choice of route. Thousands of people have been served with compulsory purchase notices and others have seen their properties plummet in value.

.jpg?updated=1660034514847)

Above: Residents and businesses have had to be moved out of the way. Image courtesy of london road/CC BY 2.0.

Sadly though, this is often the trade off when building infrastructure: to benefit millions, a minority are asked to pay a heavy price.

However, some property owners feel they have been offered unfair valuations and have criticised how they were dealt with. But perhaps the biggest source of contention has been the project’s environmental impact.

The natural cost

Even with sections like the Long Itchington Tunnel, which aim to protect ancient woodland as much as possible, about 24 hectares will be lost on Phase 1, across 25 sites. That’s around 34 football pitches.

HS2 says this only amounts to the partial destruction of these habitats, and they’re planting millions of new trees in return that they are responsible for maintaining.

“We've had to be really sensitive about the impact on the natural environment,” Thurston said. “We've got a target to plant some seven million bushes and trees along the route. We’re getting close to north of 700,000 already. ”

You could argue that people and businesses might, in time, adapt and move on from a difficult compulsory purchase of their land. But trees that have been around since the time of Elizabeth I aren’t coming back any time soon and that’s tough for some to swallow.

.jpg?updated=1660034917437)

Above: The anger has boiled over into numerous protests, from sites way out in the country to the heart of the capital. Image courtesy of JessicaGirvan/Shutterstock.com).

Many also believe the project poses a huge threat to animals and other plant life, even though efforts are being made to protect species like endangered bats and the scheme is projected to leave behind 30% more wildlife habitats than exist currently.

HS2 claims it has been employing “more stringent environmental standards” than in many other countries building high-speed tracks.

And right there you have one of the reasons why this project, which was already pricey to begin with, is now set to become the most expensive high-speed railway in the world.

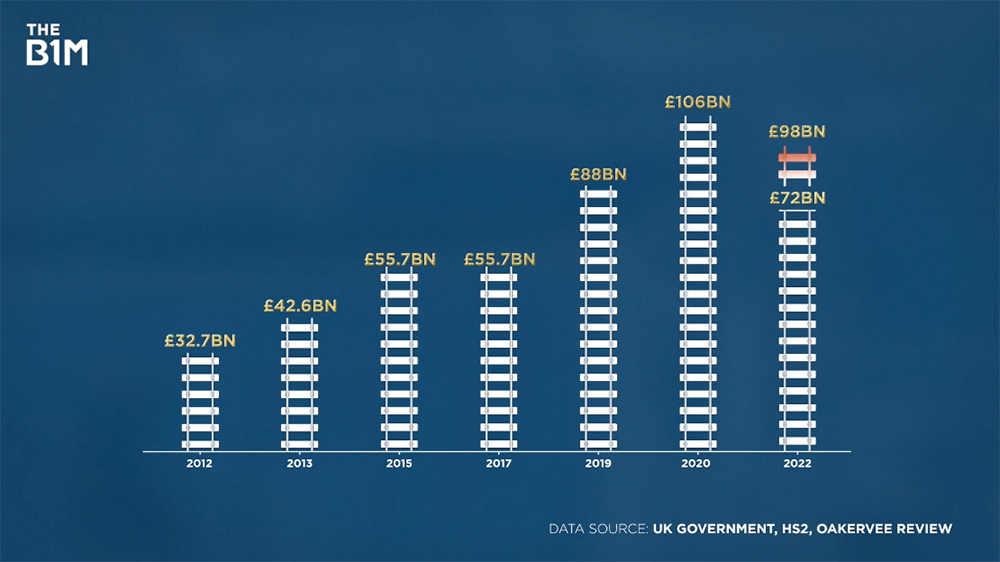

That £32.7BN figure from earlier was only the initial budget from 2012. After just one year the estimate had risen to £42.6BN. It then went up to £55.7BN in 2015 and that’s the number that parliament passed the Bill on in 2017.

Two years later, HS2 put the cost at around £88BN, while in 2020 the Oakervee Review found the bill could go as high as £106BN. Today, the government puts the cost somewhere between £72BN and £98BN.

£44.6BN is now going on Phase 1 alone – more than the entire project was supposed to cost at first – and almost £15BN has already been spent.

Above: The expected cost of HS2 has almost trebled over the past decade.

The B1M asked HS2 for comment on these budget issues and they responded that the project “remains within budget” – meaning the latest budget that’s been set.

They added that the original budget was worked-out using simple calculations and 2011 rates that didn’t take the scheme’s full complexities into account.

And with billions more in what’s called “future costs pressures” now being reported, these numbers are anything but final. The current global inflation and supply chain challenges could all start to have an impact too. Overall, it’s a lot more than what was in the budget when Parliament chose to approve it.

“Parliament was asked to make a decision in principle for the powers for Phase 1 but they were offered a set of costs which are much less than the outturn cost,” Glaister said.

“Had they been offered the decision whether or not to give the powers for HS2 at a cost of £100BN, they might have come to a different answer on behalf of us all.

“People do not understand what this is going to cost the taxpayer. If you take £100BN and divide that by the population of the country it turns out to be over £1,000 per head, bearing in mind that HS2 will be of direct value to a rather small proportion of population. So, there’s a real issue there.”

Another way of looking at that is £100 million a week, every week for 20 years.

Shifting timescales

HS2 has been hit by delays too. Phase 1 was supposed to finish in 2026 but now it's 2029 at the earliest. As for the entire network, which was meant to wrap up by 2033 – it could be as late as 2041.

2b hasn’t cleared parliament yet, so exact details of what it will look like and where it will go remain uncertain.

Along the route there have been some unexpected complications which have had dramatic consequences. In 2019, ground conditions had become, in the words of HS2’s chairman at the time, “significantly more challenging than predicted.”

In a 2019 government report, he revealed that the 2015 cost estimate for Phase 1 was made “without the benefit of any investigation of ground conditions or similar levels of detail across all areas of scope.”

More time has been needed for ground settlement – adding to the delays – and there have had to be route changes further North to avoid obstacles like salt mines.

.jpg?updated=1660035310420)

Above: A salt mine in the Northwest of England. Image courtesy of Christine Johnstone/CC BY-SA 2.0.

It’s also been revealed that the cost of buying up property for Phase 1 is over three times more than first thought – at around £3.9BN, according to figures provided to us by HS2.

The company added that “every home, business and piece of land is unique, and there are sometimes different opinions between owners, their professional advisors and HS2, about the value of a property. In all cases we seek a fair deal for both claimants and the taxpayer.”

There have been delays to the stations too, including at Euston. The latest designs were only revealed in March 2022 - seven years after the first images were made public and after construction had already begun.

And yet there’s more. One major decision has sparked anger and disappointment in the region that was supposed to benefit most from this project.

The North-South divide

London is one of the world’s top financial centres, with a higher GDP across its metropolitan area than anywhere else in Europe and a habit of spending big on infrastructure.

But many other parts of the UK, like Leeds, haven’t seen the same levels of infrastructure and public service investment, creating a North-South divide that’s only getting bigger.

The North of England has long suffered with outdated transport systems, while the capital continues to get more big projects like the brand-new Elizabeth Line.

One of the current UK government’s big pledges at the last election was to “level up” the whole country. That involves boosting local economies outside London.

“Our analysis of the most recent data, which is collected for all the regions of the UK, shows that London has really bounced back and the challenge is that the rest of the country is still lagging behind,” Henri Murison, chief executive of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, an independent body that represents businesses and civic leaders across the North, said.

“In reality, under this current government, we're not making huge progress. It may take longer to see some of the benefits of some of the levelling up projects, but they're often too short term, not focus ed enough on long term productivity, and so unlikely to yield the longer-term benefits we need economically.”

Above: Henri Murison, chief executive of The Northern Powerhouse Partnership.

But this is exactly the kind of issue that HS2 was designed to fix. Then there’s Northern Powerhouse Rail, another major programme of upgrades which would integrate with HS2 as part of a new Integrated Rail Plan for the region. Sounds like things are looking up at last.

But there’s a big problem. When those costs were getting out of hand and it was decided that part of the route had to be shelved, it was the bit running to Leeds that took the hit. That route is no longer happening, and Northern Powerhouse Rail has been downgraded.

The Eastern Leg of Phase 2b will now terminate near Nottingham, over 70 miles away. Trains will still be able to go further North, but only on existing, non-high-speed lines.

Although the intention is to get to Leeds eventually, and ideas have been put forward, nothing has been confirmed – only a study which is set to cost a further £100 million.

“There's a notional promise from government of some HS2 trains coming to Leeds. Well, we don't know how frequent or what the capacity will be, so we don't really know the value of that,” Murison said.

Above: How or whether HS2 trains will get to Leeds is now uncertain.

“We are talking to the government now about the Eastern Leg. Certainly, having travelled in and around the Midlands and the north a lot on rail you see the stark difference between the sort of frequency and regularity of services compared to London and the south east,” Thurston said. “So that's I think where we need to sort of put our focus next, working with the Department for Transport.”

But that’s not all of it. The project is still being scaled back, and again it’s the North that’s affected. Another key section connecting to the West Coast Main Line was cut. It was through here that high-speed trains would’ve continued as far as Scotland.

The Government says it’s now “committed to finding the best solution to take HS2 trains to Scotland” and will “explore alternatives that deliver similar benefits.”

In Manchester there are issues to iron out too, like the decision to build the main station on the surface rather than underground, which has been criticised by local officials.

“I think that the public opinion is wary of a government that is prepared to keep its promises to the north of England,” Murison added. “In this country, we are entirely dependent on who the occupants of number 10 and 11 [Downing Street] are for whether Leeds gets a mass transit system, whether Leeds gets its HS2 station, whether Leeds gets access to a train line that’s supposedly for its own benefit.

“The Integrated Rail Plan represented £36BN of cuts to what had originally been promised. Rather than just being an economic problem, it's also a political problem for a government that claims it's levelling up.”

Getting on with the job

To their credit, those currently working for HS2 are doing their best to move on from the past and politics and just focus on constructing the railway.

But despite the good job that teams on the front line are doing, it’s clear that what’s currently being built is a long way from what was put forward at the beginning.

So, is it time for a radical rethink or does this railway now simply have to be finished, no matter the cost? HS2 might have gone from an ambitious dream to a bit of a nightmare but the UK is far from the only country that’s had difficulty with new infrastructure.

Not just a UK problem

Many other public-funded railways have also fallen behind schedule and gone over budget. California High-Speed Rail in the US and Stuttgart 21 in Germany are just two examples.

Big energy projects don’t seem to fare much better either. The Olkiluoto 3 power plant in Finland and China’s Three Gorges Dam both faced big challenges.

.jpg?updated=1660035876792)

Above: Several other infrastructure megaprojects around the world have faced major problems. Image courtesy of California High Speed Rail Authority.

Even so, are there days when Thurston questions if the whole thing is worth it?

“You've got to believe in a project like this to do my job and all the people that work with me. You've got to believe it's an important project,” he said. “Of course, there are swings and roundabouts and all big projects have sort of dark moments, but the highs more than outweigh the lows.

“Taxpayers generally can and should have confidence that we’ve set ourselves up now to deliver the project for the budget we’ve committed to government.”

The power of big infrastructure

When done properly, the pay-off of big public projects can be huge. They have the ability to shape our world and change its course.

Better connectivity between countries; cleaner, more affordable energy; lifting people out of poverty; limiting the impact of natural disasters – all are made possible by infrastructure projects like this.

That’s why so many national governments look to schemes like this and approve them despite their financial, social and environmental costs. Infrastructure has the potential to make a big lasting impact and enable countless other aspects of our societies.

Above: Infrastructure projects like HS2 can create something tangible and concrete to show voters. Image courtesy of HS2.

But the bigger the rewards, the bigger the risks and costs. The stakes all around get much higher and everything becomes magnified.

Yes, things go wrong in other parts of construction. We’ve seen unfinished skyscrapers, which usually happen when private developers run out of cash. But when it’s public money that’s on the line, that word “unfinished” becomes unthinkable.

“I do think there's a problem in the British system and maybe in other countries too, whereby governments get committed to a controversial idea,” Glaister said. And because it's controversial, they make firm promises. And then if it turns out on further investigation not to be such a good idea, they defend the idea rather than being able to review it.”

“I’ve said before this project divides opinion,” Thurston said. “It draws a huge amount of public money, it's disruptive, it takes a long time and people struggle sometimes to justify the investment in it. But of course, those railways that have invested in high-speed rail have never regretted it.”

Making an impact

Britain’s High Speed 2 is a potent reminder of the power of infrastructure. It shows us once again what the construction industry can do and the impact it can have on so much of our lives.

The teams pulling off the extraordinary feats of engineering to create this railway are quite literally writing this country’s next chapter into its land.

For whatever the mistakes of this project’s management or the discourse around its very existence, that’s something that can’t be taken away from these amazing people.

Above: Those working on High Speed 2 will inspire future generations of engineers. Image courtesy of HS2.

It epitomises the story of the infrastructure megaproject. Huge benefits are laid out for future generations that citizens of today must bear the cost of – just as our predecessors did for us.

The promise of a bigger prize ahead is used to counter painful issues and becomes the lens we see them through. Fear of stopping drives people on. Supporters and detractors are selective with their facts. We’re told that we’ll one day forget it all and only experience the benefits, but that verdict is cruelly deferred by decades.

Only time will reveal the true extent of HS2’s success and whether the decision to carry on was really worth it, but like so many infrastructure projects around the world it will undoubtedly leave its mark on this nation.

It’s not the first massive scheme in history to daunt people with its costs, challenges and ambition – and it won’t be the last.

Video presented and narrated by Fred Mills. Special thanks to HS2, Mark Thurston, Stephen Glaister and Henri Murison. Additional footage and images courtesy of HS2, Alisdare Hickson/CC BY-SA 2.0, Ardfern/CC BY-SA 4.0, BBC London, California High Speed Rail Authority, Channel 4, Conservatives, Consorzio Venezia Nuova, Crossrail, DB Projekt Stuttgart-Ulm GmbH, djim/Chartridge Photographic/CC BY 2.0, 5 News, Georgia Power Company, Google, ITV News, Iwan Baan, JessicaGirvan, Karen Bruce/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Labour Party, london road/CC BY 2.0, metrogogo/CC BY-SA 2.0, Michael Warner, Mott MacDonald, Olesia_Ru, Roger Marks/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Shutterstock.com, Sky News, Sunday Times and The Times, Tapani Karjanlahti/TVO, The Telegraph and UK Parliament.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.