Why New York is Building on TOP of its Skyscrapers

- Youtube Views 631,804 VIDEO VIEWS

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotion for Masterworks.

NEW YORK is full. So full that it's now building on top of its existing high-rises to create more space.

One Wall Street is one of the city’s oldest skyscrapers. It used to be an office building but has now been converted into apartments. In doing so, six additional floors have been added on top.

Adding new floors to a building is clearly not a simple task, let alone on top of a skyscraper in the middle of one of the busiest cities in the world.

The average concrete slab in a New York building is eight inches thick and weighs thousands of pounds. Adding new floors means adding a lot more weight to a building that was not designed for it. If it’s done wrong it could crush the floors underneath. This is how New York built on top of an historic skyscraper.

Above: Construction work on top of One Wall Street. Image courtesy of One Wall Street.

It has taken eight years of construction to convert this Art Deco skyscraper from offices to apartments. It is the largest building in New York City to undergo this type of adaptive reuse.

While the exterior has remained mostly the same, the inside of the building has been nearly completely gutted.

A total of 566 homes now occupy One Wall Street. Hundreds of new landmark-approved windows were added, the building’s mechanical areas as well as 30 of its lifts had to moved from the perimeter to the core, and, of course, six additional floors were added to the top in a way that would not crush the floors underneath.

“There were a lot of challenges. You know, we're engineers, we're thinkers, there are things we like to work on. This had a lot of those, and it was a challenge, but it was nothing insurmountable,” Mark Plechaty, principal structural engineer at DeSimone Consulting Engineering explained.

“I run a team of about 20 people. The One Wall Street project started our involvement in 2014. So it's been almost, essentially a decade's worth of work, on the building.”

Above: One Wall Street under construction. Below: The skyscraper completed. Images courtesy of One Wall Street.

So why did this have to happen? Why did this building have to be gutted and transformed? Well, the nature of cities is changing.

One Wall Street occupies a full city block bound by Broadway, Wall Street, New Street and Exchange Place. It is right in the middle of the Financial District, the beating capitalist heart of the city. This is where the Stock Exchange is, the Federal Bank and One World Trade Centre.

The neighbourhood has seen a rapid change in recent years as demand for office space has dwindled and demand for housing has skyrocketed.

People are looking at these once towering office buildings and wondering if they could be put to better use. If people could actually live in them.

But office buildings aren’t designed to be lived in and converting them into apartments isn’t simple. Offices tend to have large floor plates that don’t divide into flats easily.

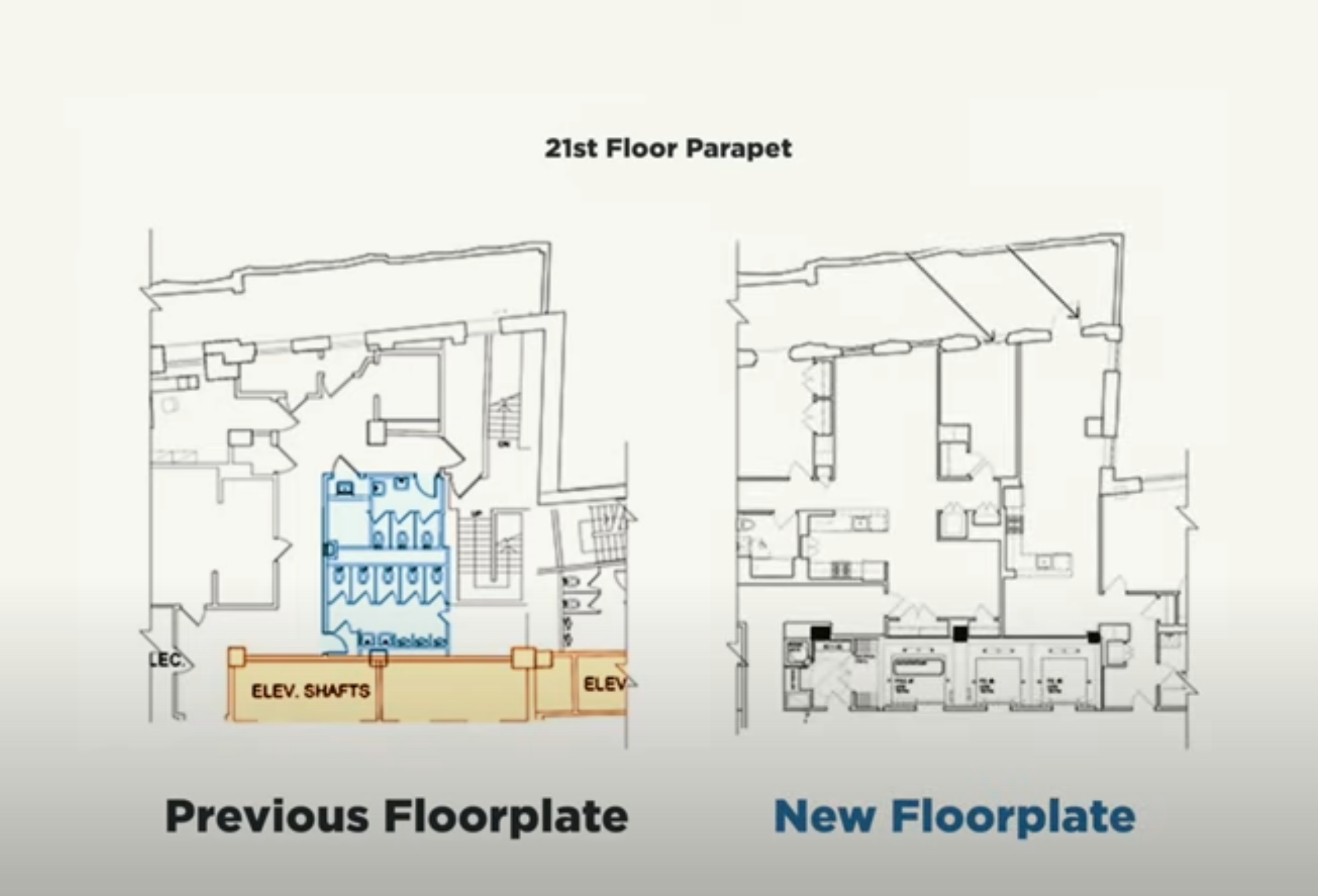

Above: Comparison of the floorplates after the renovation of One Wall Street. The bathrooms are in blue, the elevators in orange. Image courtesy of One Wall Street.

They often have their plumbing, electricals and elevators in the wrong place and they don’t allow for enough natural light to reach the very centre of the building.

“I know that there are some projects going on with a bigger office building and they are actually taking one of these and cutting out a core like an atrium, so you can actually get the light and air that you need,” Lilla Smith, director of architecture at Macklowe Properties told The B1M.

One Wall Street was among the city’s earliest skyscrapers, built at the beginning of the 20th century. It was designed by architect Ralph Walker.

“The original building that was completed in 1931, it's such an iconic and significant building in New York City,” Smith said.

“The original tower was landmarked by New York City in the 1980s, 1990s, something like that. So once it becomes a landmark, you cannot touch the exterior. You cannot knock it down,” Plechaty added.

The building is a prime example of the Art Deco movement that dominated Manhattan’s skyline in the 1920s and '30s, which was why it was given landmark status.

Above: The building's original 1930s facade "ripples" in the sunglight. Image courtesy of One Wall Street.

“It has a limestone facade that Ralph Walker actually called a drapery or a curtain wall, and this undulating facade is absolutely gorgeous in sunlight,” Smith said. “Even if there was an opportunity, if it weren't landmarked, we certainly would not have taken it down.

“So that was one reason. But the second was it would be very complicated. We have the subway below us. If we were to demolish something and, you know, structurally, I think it would be even more complicated to build a new tower.”

While knocking down the building would have been complicated, there was nothing simple about retrofitting this enormous block of offices.

30 elevators had to be demolished, then new ones rebuilt in the centre of the building. Mechanical rooms which had faced the New York Stock Exchange also had to be moved.

“The office demand for elevators is much different than residential because you've got those rush hour points in the day. And we have ten elevators for the apartments, down from the 30," Smith continued.

"We put them all centralised into a core in the centre building. Same thing with these staircases so that made it much better, for efficient layouts and as well as the ability to have, you know, light in there as well.”

The decision was also made to add six additional floors to house more apartments and take advantage of the spectacular views at the top.

Those levels were added to the annex, a 30-storey section of the building that was constructed in the 1960s. One of the benefits of adding the floors to this part of the building rather than at the very tip of the skyscraper is that the annex is incredibly sturdy.

“So the original design was an office building with a heavier than required design load. So it was designed for a much heavier use than an office originally,” Plechaty explained.

“The weight requirement for residential is significantly lower than it is for office. So on the existing building that was 30 storeys we took advantage at each floor of that reduction. It adds up significantly where you can take advantage of it. We still had to strengthen the upper floors to receive the added weight.”

Even with the sturdiness of the building below they still needed to reduce the weight of the additional floors.

Above: Voided slabs were used to reduce the weight of the additional floors. Image courtesy of One Wall Street.

To do this they used voided slabs. These slabs were filled with plastic cylinders before a finishing layer of concrete was put on top.

“We made the added weight at the top less by using these plastic bubbles inside the slabs. So what looks like a finished product, like a typical standard flat concrete floor plate, in fact has inside it plastic bubbles inserted at strategic locations to reduce the weight further,” Plechaty said.

They did leave some areas as solid concrete, especially where structural columns came through the floors, but most of the slab was built using this technique.

This process reduced the overall weight of the floors by about a third. It was also far easier to construct than, say, if they had used steel beams.

“You would have had to install the tower crane, which is extremely expensive, you’d have to dismantle the steel into smaller pieces, bring it up by elevator, reassemble it," Plechaty said.

“With concrete, you could bring the concrete in, it can be pumped, the rebar can be brought, the metal bars can be brought up to the elevator very easily. And the plastic bubbles are very lightweight. So everything was brought up through the construction hoists and then installed at the top.”

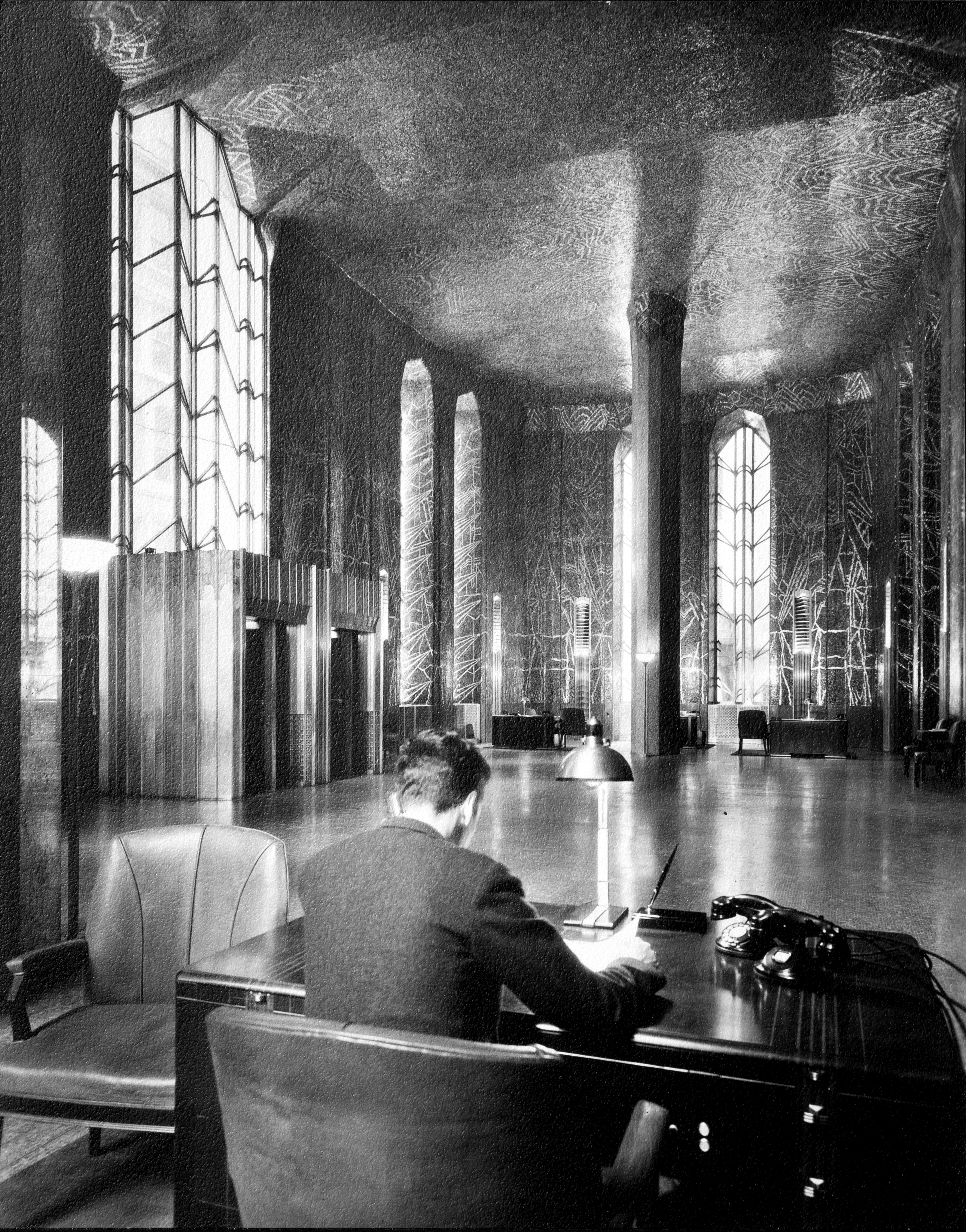

A lot of effort went into retaining the Art Deco aesthetic throughout the rest of the building. The Red Room is a glittering reception room that features floor-to-ceiling mosaics designed by famous Art Deco artist Hildreth Meière. It has been closed off for nearly two decades but has now been lovingly restored.

“The developer spent over $1M restoring the mosaics,” Smith said. “It's 33 feet tall, and the mosaics were cleaned with non abrasive solutions.

“You can imagine that from 1931 to, you know, 2019, that's nearly 100 years' worth of cigarette smoke or whatever it would be on these mosaics. But it was carefully restored.”

Above and Below: "The Red Room" in its original glory. Images courtesy of One Wall Street.

One Wall Street has now completed and welcomed the first of its new residents. So, is this building a symbol for the future of New York? As cities change buildings have to change and adapt with them.

Perhaps nothing is more emblematic of the current state of the city than one of New York’s ancient financial skyscrapers turning into apartments. We might be seeing many more of these iconic buildings transforming, or gaining floors, in the future.

This video and article contain paid promotion for Masterworks, you can skip their waitlist here.

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of One Wall Street.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.