Welcome to the Skybridge Renaissance

- Youtube Views 743,782 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

WHILE the idea of linking buildings to create a unified structure is nothing new, as our cities become ever more densely populated, and as the scale and complexity of structures continue to increase, architects and engineers are taking the concept of skybridges to new heights.

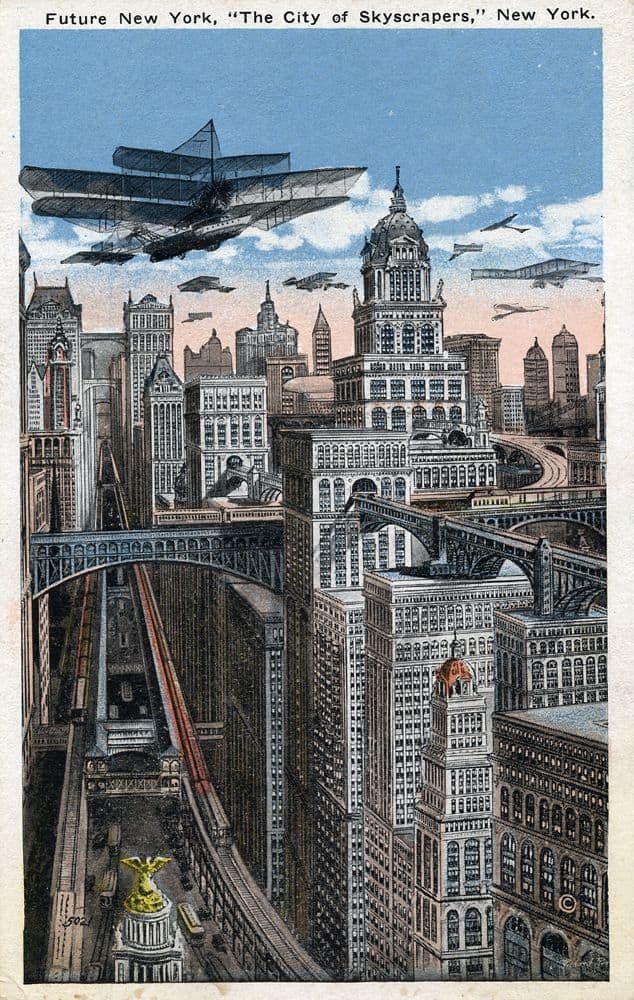

During the 19th Century, when engineering breakthroughs and the industrial revolution began to drive our cities skyward, many began to envisage a future where vast networks of elevated walkways would aid citizen movement above street level.

Above: It was once thought that skybridges would become commonplace in large cities (image courtesy of R. Rummel).

While this vision never came to be, the concept of skybridges went on to become adopted in numerous locations around the world; primarily as pedestrian

links in shopping malls, public transportation networks or as protection from the elements in places with extreme climates such as Dubai or Calgary.

Though the concept proved practical for certain purposes, the feeling of isolation created and the negative visual impact that these structures had on their surrounding streetscape, prevented their widespread adoption.

However, since the turn of the 21st Century – with the majority of the global human population now living in cities, and placing significant demands on space in urban areas – the concept of skybridges has been reimagined.

THE RISE OF THE SKYBRIDGE

Attitudes toward skybridges first began to shift in 1998, when architect Cesar Pelli designed a two-storey observation deck and walkway to unite what would then become the worlds’ tallest buildings; the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur.

The skybridge made the buildings an instantly recognisable symbol of Malaysia and the popularity of the public observation deck within the structure saw the purpose of skybridges change from simple, elevated walkways to destinations in their own right.

Above: The Petronas Towers changed the perception of skybridges and made them destinations in their own right.

From here, the concept began to take-off in emerging economies throughout the 2000s, with many statement projects incorporating impressive skybridges into their designs.

Saudi Arabia’s Kingdom Centre and Shanghai's World Finance Center both incorporated observation decks into skybridges at their summits, while Bahrain's World Trade Center was unified by no less than three skybridges that used their positioning between the sail-like towers to house wind turbines and generate a portion of the building's power.

The design of China’s Linked Hybrid – a multi-use development in Beijing – uses eight skybridges to unify the complex and create a series of public and private spaces where occupants can share the resources of other buildings while fostering a pedestrian-orientated environment.

THE NEXT LEVEL

While skybridges had evolved from simple walkways to striking features, it was the Marina Bay Sands hotel in Singapore, designed by Moshe Safdie, that largely re-wrote the rulebook and fundamentally changed the way we see skybridges today.

Above: The Marina Bay Sands in Singapore largely rewrote the rulebook on skybridges.

The Marina Bay Sands scheme took the skybridge concept to a completely new level; connecting three 207-metre towers with a 340-metre long “skypark”.

By unifying the resort in this way, Safdie created 12,000 square metres of uninterrupted space that offered guests a chance to circulate and enjoy the resort’s amenities against a backdrop of breath-taking city views – views that would otherwise only have been afforded to those in the highest suites.

While construction of the skypark presented a significant engineering challenge and ultimately resulted in the resort becoming one of the world’s most expensive skyscrapers, the space it brought to the development broke new ground and led to the practice of incorporating fully functioning “skyfloors” into several skyscrapers around the world.

Above: China's CMG Headquarters took the concept even further, uniting its two towers and vastly increasing its floor area.

Returning to enclosed examples, China’s CMG Headquarters (formerly the CCTV Headquarters) in Beijing connects its two towers from the 37th storey upwards, vastly increasing the amount of lettable floor area within the structure while creating room for green spaces and an open plaza at street level.

Meanwhile, in New York, the American Copper Buildings are connected by a double floor skybridge that offers residents of the two towers a range of amenities including pools, a gym and a resident’s lounge.

While creating two towers increases the views and in turn appeal of residences, the spaces within the skybridge create a shared, social environment for residents while reducing the overall number of facilities that would otherwise have been required in two detached buildings.

In one of the boldest examples of this trend to date, Raffles City in Chongqing, China, sees four of the development’s eight towers united by a 300-metre long, 26-metre high enclosed linear park named the Crystal.

Above: Raffles City in Chongqing and "The Crystal" skypark under construction (image courtesy of CapitaLand).

Again designed by Safdie, the space offers a number of amenities from pools and restaurants to landscaped gardens.

THE FUTURE IS NOW

Far from being restricted to Asia, complex skybridges are now being incorporated into an array of developments around the world.

The upper third of The Arc, which recently topped-out in Vancouver, will offer residents unparalleled amenities including a glass floor swimming pool above the void between the two towers.

Above: The Address Sky View Hotel and Residence in Dubai will compete later this year (image courtesy of Graham Hart).

2019 will also see the completion of Dubai’s Address Sky View hotel and residential towers which are united by a multi-storey skybridge offering guests and residents an array amenities.

Meanwhile in Melbourne, Collins Arch maximises the amount of space it can create on its height-restricted site with a number of floors that unite the hotel and residential tower with its commercial counterpart while creating open green space at street level.

Above and Below: In Melbourne, two developments under construction are set to redefine the city with their impressive skybridges (images courtesy of Woods Bagot and SHoP Architects (above) and SP Setia, Cox Architecture, Fender Katsalidis Architects (below).

Just a short distance away, work has now commenced on the Sapphire by the Gardens and Shangri-La Hotel development which is set to be united by a two storey skylobby for shared use between the two towers.

In London, two of the residential towers at Embassy Gardens in the city’s Nine Elms district will be linked by an impressive skypool.

With advancements in construction methods and materials, and with innovations like horizontal elevators being trialled, the future of skybridges and building design seems to know no limits.

While we are still some way from that future envisioned in the 19th Century, the evolution of skybridges from simple walkways to critically important, defining features has now opened the door to a range of possibilities that are only limited by the imagination and ambition of engineers and developers.

Footage and images courtesy of Safdie Architects, SHoP Architects, Max Touhey, Emaar Properties, Will Femia, Concord Pacific, ARUP, Joe Mabel, Ildar Sagdejev, CapitaLand, Iwan Baan, Edward Hendricks, Woods Bagot, Tim Dickson, HAL Architects, MIR, Tom Merton, François Schuiten, R. Rummel, Adam Smok, Booth Muirie, Dan DeLuca, Adam Jan, Tony Hoffman, Nick Lehoux, Sunil Shah, Ty Cole, Graham Hart, SP Setia, Cox Architecture, Fender Katsalidis Architects and ThyssenKrupp.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.

Comments

Next up