Sheltering Syria: Earthbags, Community Labour + 3D Modelling

- Youtube Views 8,704 VIDEO VIEWS

Ancient and modern building techniques blend together in Anas Aljbain’s design for transitional refugee shelters, writes Emma Crates. Video produced by Fred Mills.

THE NUMBER of displaced people around the world is at a record high. In 2015, 65.3 million people were forced to flee their homes due to war or persecution, according to the UN refugee agency UNHCR. To put that into context, that’s roughly the equivalent of the entire population of the UK – or France – being made homeless in the same year.

The unfolding crisis has no easy solutions. One of the first and most obvious challenges is how to provide adequate shelter for so many people, giving them both protection and dignity.

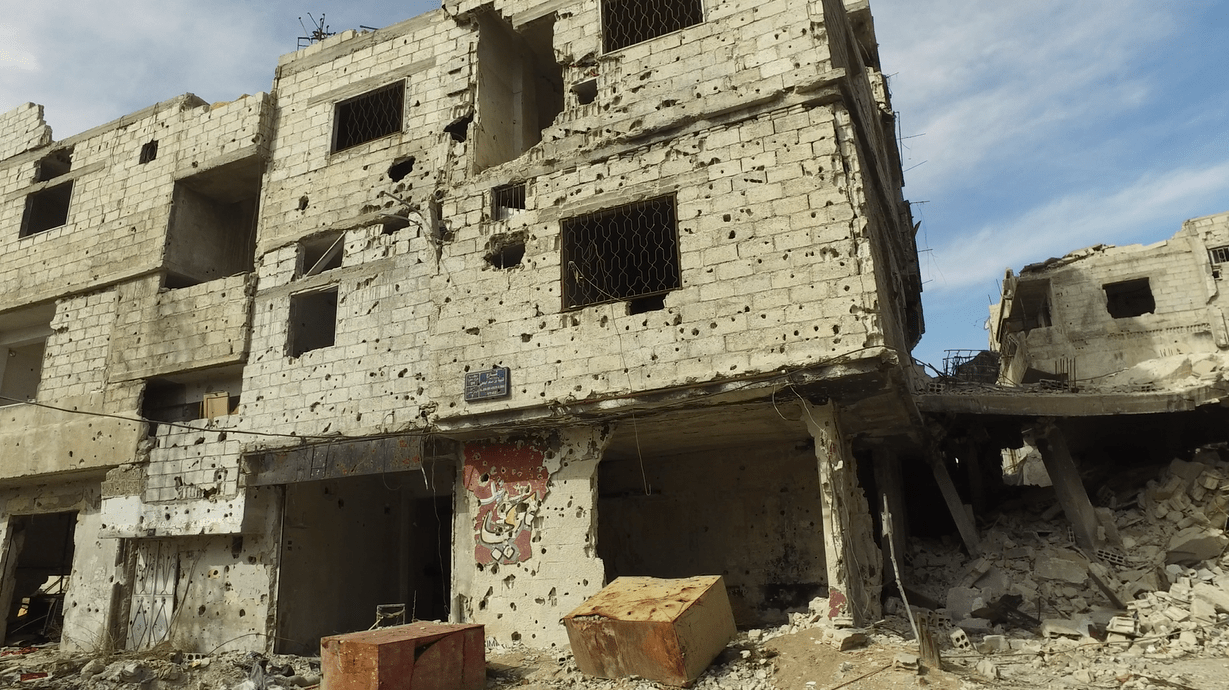

Above: The intense war in Syria has forced millions to flee their homes. This image shows a near-destroyed suburb of Damascus.

Syrian-born architect Anas Aljbain has been wrestling with this problem for the past three years. Joining UNHCR in 2013, he worked on a variety of initiatives, including partitioning up schools and community centres to provide temporary accommodation. He also developed a housing solution that is an intriguing blend of modern and ancient techniques.

"65.3 million people were forced to flee their homes due to war or persecution in 2015"

Building on the work of Iranian architect Nader Khalili, Aljbain’s proposal is to create earthbag houses. As the name suggests, this involves filling bags with rammed earth and sand, placing them on top of one another and then covering them with plaster.

“Mud used to be the traditional way to build a house,” he says. “But after cement was invented, everyone liked using that. They thought it was more stable. But they forgot the environmental and sustainability benefits of this more traditional way of building.”

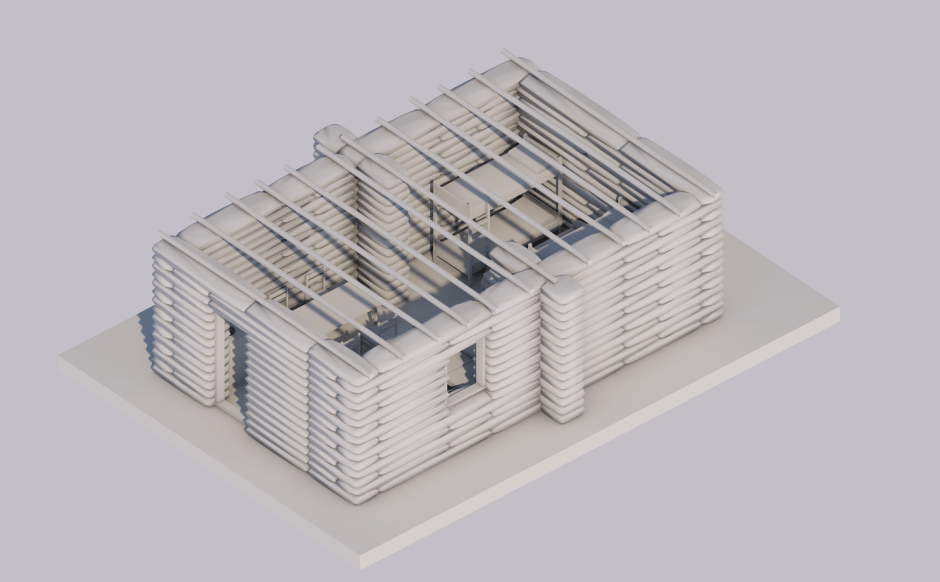

Above: Aljbain's pilot transitional shelter in north east Syria.

Above + Below: The structure is formed by bags filled with earth and sand which are then stacked on top of one another and plastered over.

The history of earth structures does indeed stretch back to the beginnings of civilization – from ancient grain stores in Egypt to parts of the Great Wall of China. In a modern context, and particularly during a humanitarian emergency, the benefits are multiple. Earth and sand are abundant materials that do not need to be transported from abroad; the technique can be carried out with minimal training; designs can be adapted according to local need. In addition, owing to their thickness and weight, walls built from earth bags are strong, have excellent thermal properties and are better able to withstand high winds or other destructive forces such as bullets or even mortars.

But when UNHCR decided to build a test house in northeast Syria, the refugees, already traumatised by war, were sceptical.

“They said, ‘Now you want us to get back to the Stone Age, and live in a mud house?’” Aljbain remembers.

It was the use of digital 3D modelling that convinced them. Aljbain was able to show them the build sequence on his tablet, demonstrating how the structure would finally look and how housing clusters and communities could be created.

Above: Aljbain modelled the pilot shelter in 3D using ARCHICAD (by GRAPHISOFT) and was able to demonstrate the build sequence to local people on a tablet device.

Volunteer refugees started to participate, coming up with their own ideas.

“They suggested using wire mesh and rebar to reinforce certain areas,” Aljbain says, “I was worried about the roof, but they said, don’t worry, we have a special kind of dirt in this area which is a waterproofing material. We’ve been using it on our roofs for the last 700 years.”

Above: Volunteer refugees contributed their own ideas, including for the roof.

For the walls, the soil ratio in the earth bags was 30% clay and 70% sand. The ratio can be modified for different climates and Aljbain says that his

design can be tweaked for local conditions, for example adding cement to the base of walls to protect against flooding.

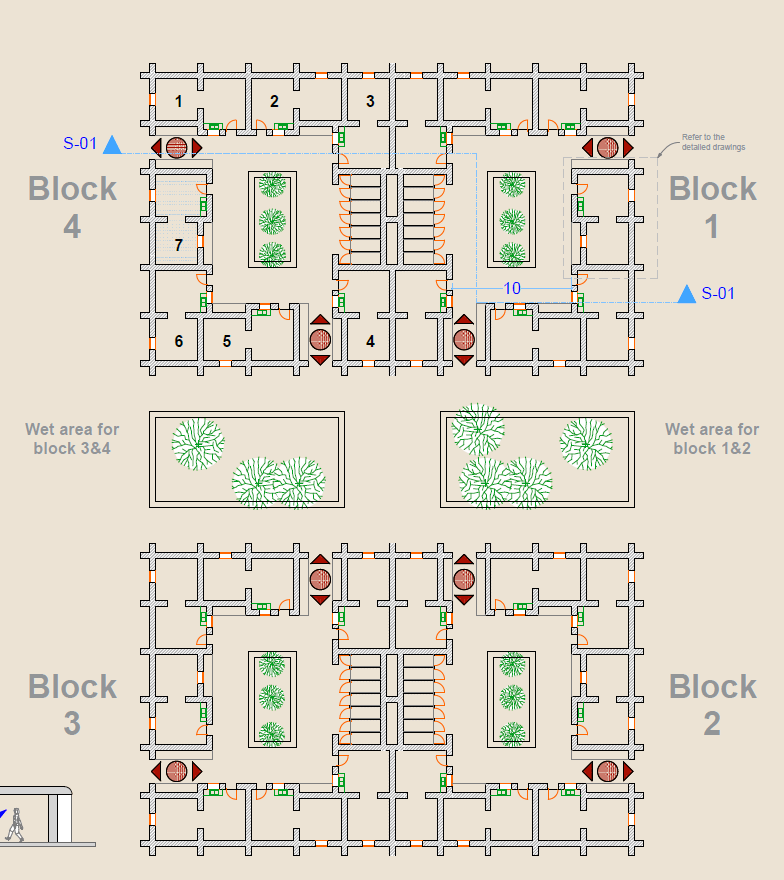

Aljbain’s masterplan places the units next to each other with adjoining walls, in order to save materials. There are shared courtyards at the centre of each block where children can safely play.

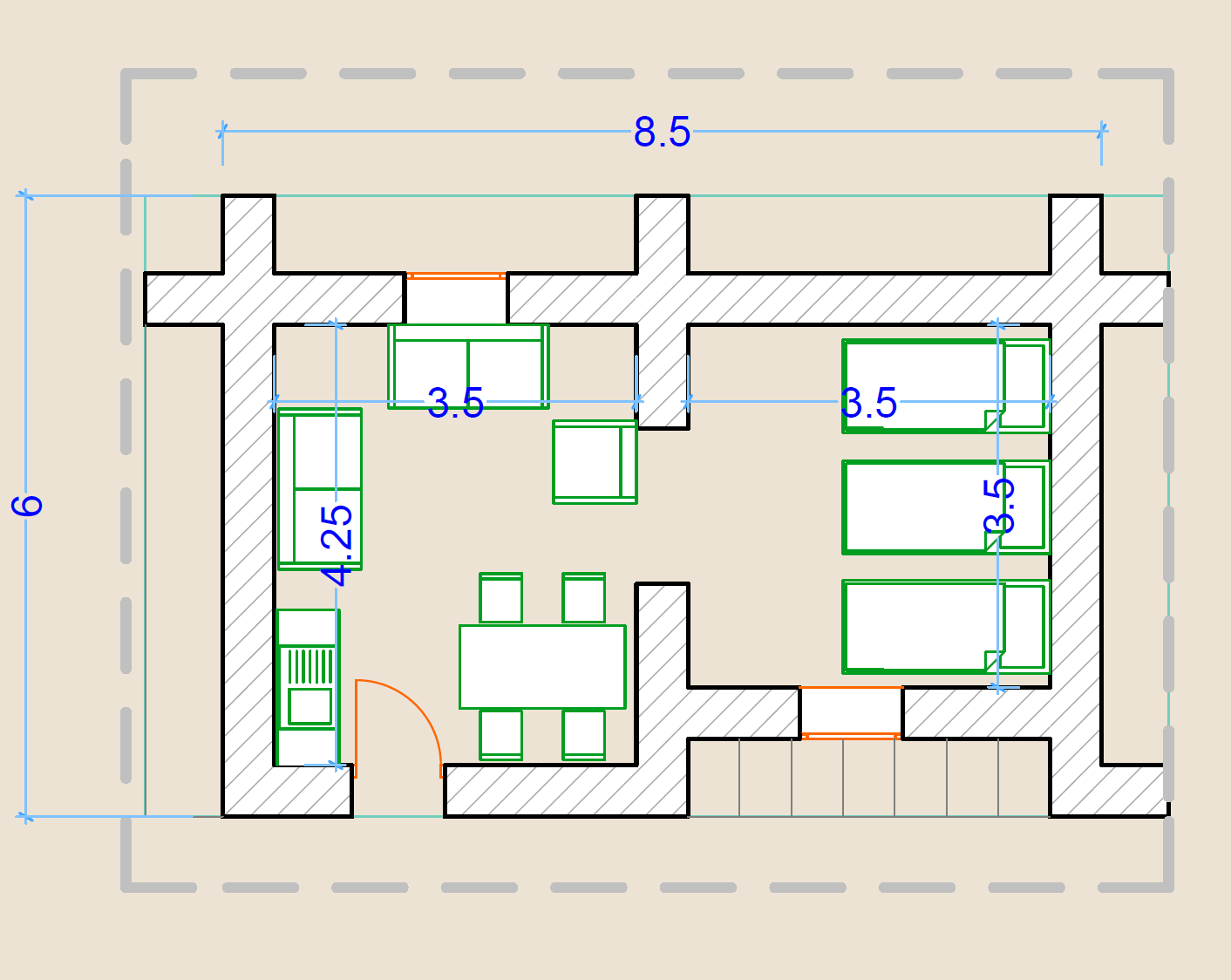

Above: A template floor plan for one shelter unit, and Below: A suggested sector plan for multiple units.

It took six labourers less than a week to construct the test house in northeast Syria last year, at an estimated cost of USD $41 per square metre.

Now, Aljbain hopes that the house could be a template for other refugee communities around the world. One of the design’s advantages is that it empowers local communities, giving refugees the chance to earn money building their homes under the UN’s Cash for Work programme.

“It’s the best option because it uses local materials, employes unskilled workers and is very cheap. You can use a lot of people. You can also do it on a massive scale,” he says.

"I hope that I can support people with whatever I know or have to rebuild my home country”

Aljbain is currently living in Canada, working for a Masters degree at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. His study subject is close to his heart: how to rebuild devastated countries after war.

“I hope that I can be part of the reconstruction phase when things settle down in Syria. I hope that I can support people with whatever I know or have to rebuild my home country,” he says.

To support the efforts of the UNHCR in Syria please click here.

This video was kindly powered by Viewpoint.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.