Japan’s $64BN Gamble on Levitating Bullet Trains Explained

- Youtube Views 9,523,528 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Fred Mills.

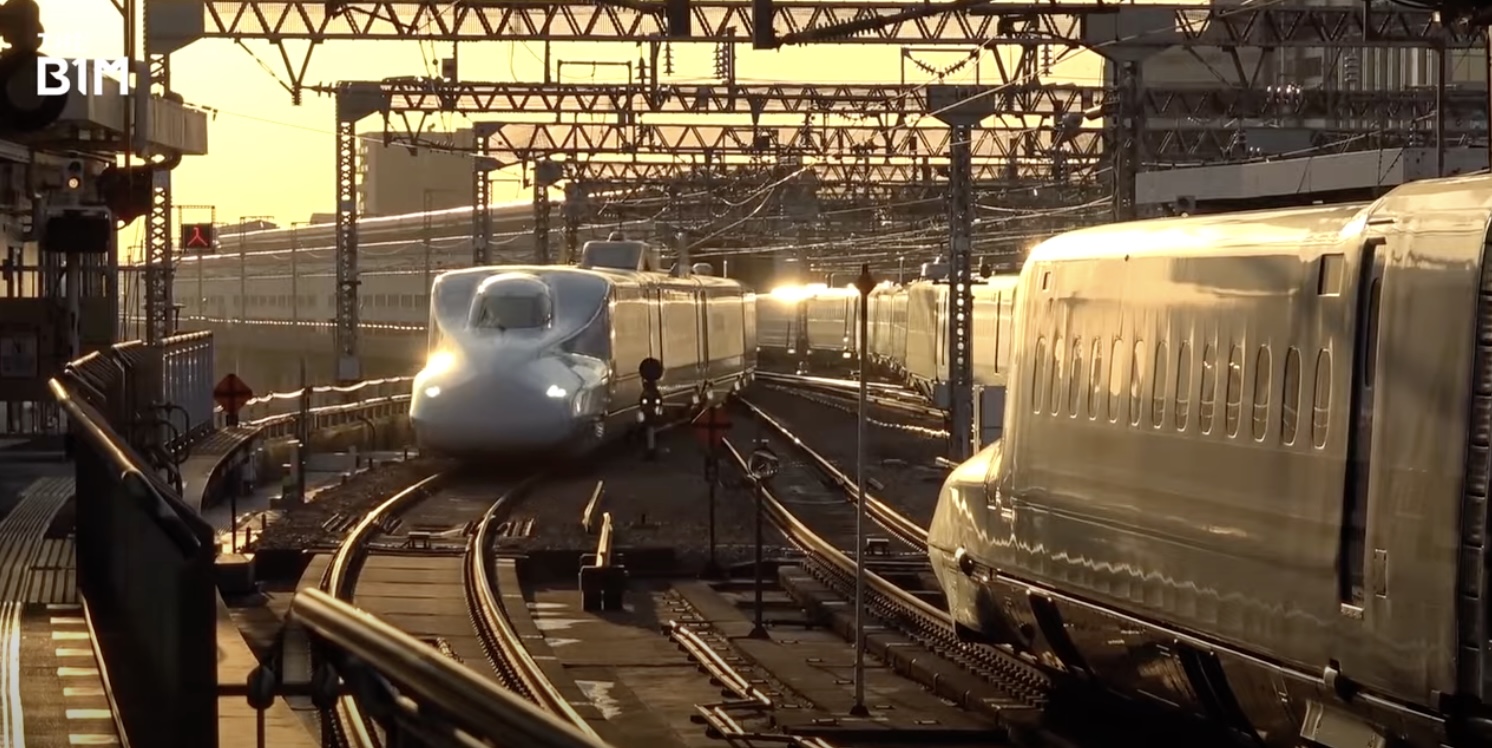

IF YOU want to get somewhere in Japan fast, the bullet train has you covered.

An engineering marvel forged in the aftermath of the Second World War, it’s carried more than 10 billion passengers at speeds of up 320 kilometres per hour - and helped create the world’s third largest economy.

But that’s not enough for Japan and the country is now building the world’s fastest passenger train; a system that’ll move at twice the speed of current bullet trains and cut journey times in half, all by doing away with one fairly fundamental component - wheels.

Using magnetic levitation, these new trains will hover ten centimetres above the ground, eliminating the friction that comes from being in contact with the rails.

But the new line has proved deeply controversial - grappling with delays, skyrocketing construction costs and a fierce debate over environmental concerns.

Now nearing completion, the world is waiting to see whether the project will successfully “hover above” its challenges and make a quantum leap for transportation or prove a step too far.

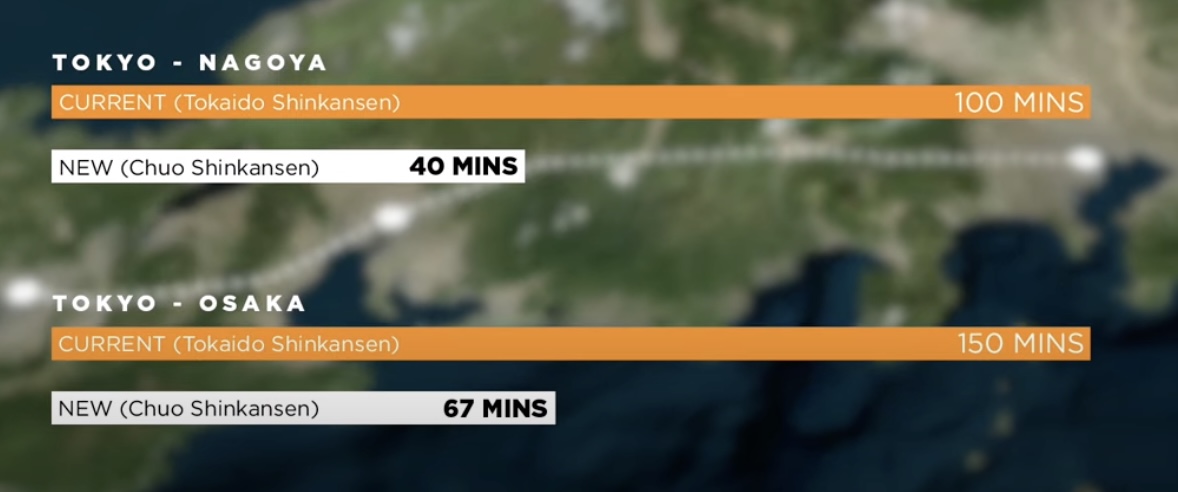

Above: Japan's new magnetic levitation line is likely to dramatically reduce travel times.

Japan kind of knows a thing or two about trains.

The country was the first in the world to develop high-speed rail, with construction of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen line between Tokyo and Osaka in 1959.

Back then the Japanese people, and indeed the rest of the world, were skeptical of the country’s massive investment into rail - and many thought it would soon be outdated in an exciting new era of air travel and highways.

Nevertheless, the first high-speed line opened in October 1964, ready for Tokyo’s first hosting of the Olympics.

It cut the travel time between Japan’s two biggest cities from nearly seven hours to just under four. Proving an instant success, the line served more than 100 million passengers in less than three years.

That same trip on a modern bullet train is now done in two and a half hours.

When the new Chūō Shinkansen line completes it will be done in 67 minutes.

Above: Japan's first bullet trains were met with skepticism.

At full speed the Chūō Shinkansen trains will move at 500 kilometres per hour - although a 2015 test run hit a world-record 603 kilometres per hour.

Now, it’s pretty widely-agreed that those kinds of speeds are basically impossible for a conventional bullet train to hit - they eventually all become limited by the friction that’s created by their wheels.

To solve that problem Japanese engineers looked back in time to a technology that has actually been around since the early 1900s: magnetic levitation also known as “maglev”.

In fact, concepts for maglev trains date back to the 60s and the world’s first (and so far only) commercial maglev line has been in operation since 2004 - running between Shanghai’s city centre and its airport.

The Central Japan Railway Company, or JR Central, has modernised this technology using superconducting magnets.

Electromagnets are cooled to -269 degrees, allowing trains to levitate higher above the tracks; but the trains need to be moving at speed before the magnets come in.

Above: The dotted line marks where the new maglev line will be built.

Once the train reaches 150 kilometres an hour by itself, maglev kicks in and the carriage is lifted off its rubber wheels.

The train then interacts with a set of coils in the track, one used to levitate its mass, and the other to propel it forward.

Now, without the wheels, the carriages can travel at incredible speeds. The trains are also completely autonomous - controlled by the track, rather than a driver - a measure which it’s claimed makes collisions or accidents far less likely.

The Tokyo to Nagoya line has been under construction since 2014 and is expected to open in 2027.

A further extension linking Tokyo to Osaka will begin to be built straight afterwards and open as early as 2037, ten years ahead of schedule.

Unlike the existing bullet trains whose tracks hug the Japanese coastline, Chūō Shinkansen will be 90% underground, cutting beneath the Southern Alps.

256-kilometres of the 285-kilometre-long line will be in tunnels.

Above: The new line will be built under Japan's Southern Alps.

The reasons for this are twofold: firstly maglev trains work better when they travel in the straightest line possible, and burrowing beneath the mountains avoids Japan’s more earthquake-prone coast.

Although, in taking this approach JR Central has ended-up digging some of the deepest tunnels Japan has ever seen.

That’s raised a number of environmental concerns, especially in Shizuoka Prefecture where tunnelling threatens the basin of the Ōi River, a major water source for the region.

While environmental studies have found that the risk of disturbing the basin is low, Local governments have criticised these reports for being in their words “insufficient and hasty”.

The incumbent Governor of Shizuoka even ran on a platform opposing the railway, successfully winning an election in June 2021 where Chūō Shinkansen was a key issue.

This controversy combined with unexpected hurdles in the construction of new stations has taken the project’s cost from $13.7BN to a staggering $64BN, making it one of the most expensive megaprojects ever undertaken in the country.

The hefty price tag is now leading many in Japan to question whether the new line is worth it at all.

Above: In the face of so many drawbacks, many are now questioning whether Japan's regular bullet trains need to be upgraded at all.

Indeed there are a few drawbacks to Japan’s maglev. Once completed they will be more expensive to run than regular high-speed trains as they consume more energy - though you could argue that they’d enable greater economic growth.

They also won’t be able to hold as many passengers within their smaller carriages and won’t be able to travel as frequently.

Traditional bullet trains run on the Tokyo-Osaka line roughly every three minutes. Because maglev track switches take more time it will only be possible to run a maglev train once every ten minutes.

Japanese rail companies have also previously been able to make back a lot of money by selling their technology overseas.

But a noticeable new player has emerged on the scene since the advent of the first bullet train back in 1964: China.

Above: China has taken over the high-speed rail market.

It’s now the king of high-speed rail and the country is home to two-thirds of the world’s entire high-speed network.

While none of its intercity lines are maglev, China is beginning to develop its own version of the technology.

In July 2021 it tested a maglev train that reached 600 kilometres an hour - almost breaking the record set by Japan.

That train could theoretically travel from Beijing to Shanghai in three and half hours, faster than the four and half hours it takes by plane.

China doesn’t need to buy Japan’s technology, and the rest of the developed world is still playing catch-up with regular high-speed rail.

So why is Japan so intent on building this maglev line and why did the government grant JR Central a loan to finish it ten years ahead of schedule?

Above: Maglev could unite Japan's biggest cities in a profound way.

If Chūō Shinkansen is successful, then it has the potential to create a commutable distance between the country’s two largest cities, linking the region between Tokyo and Osaka in a pretty profound way.

It’s a prize that’s becoming increasingly alluring around the world.

Megacities, or megalopsises, are systematically being made of China’s Pearl River Delta and Jingjinji region through strategically placed infrastructure.

While, less formally, the lines between cities in the Northeastern United States, from Washington DC to Boston, are being blurred. It’s the same in Western Europe.

Merging major cities like this has the potential to create economic powerhouses on a scale we’ve never seen before.

When the bullet train first began construction more than half a century ago, the world ridiculed it. But it ultimately allowed Japan to grow, connecting regions and sharing prosperity.

In the decade that followed it’s opening, Japan went from an economy that was just 10 percent the size of the US to the world’s second largest.

Time will reveal if this new line can levitate the country to further success.

Video narrated by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images courtesy of Nozomi 503, 2rue/ CC BY-SA 4.0., Nadate/ CC BY-SA 4.0., Scott Stevenson, Saruno Hirobano/ CC BY-SA 4.0., Yamanashi Prefectural Maglev Exhibition Center, Microsoft Corporation / Earthstar Geographics, and SCMaglev / Central Japan Railway Company with special thanks to Novomi 503.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.