Health and Safety in Construction: A Visual History

- Youtube Views 17,093 VIDEO VIEWS

Video hosted by Tom Payne.

IN the 19th century, when navvies were building the UK’s railways, three workers died for every mile of track laid, with the death rate rising much higher in tunnelling sections.

Since this time great strides have been made to improve health and safety on construction sites. We take a look back at the key moments that have shaped today’s higher standards.

Above: A total of 32 workers were killed and 140 were seriously injured building the Woodhead Tunnel.

The Woodhead Tunnel, between Manchester and Sheffield in the UK, was one of the most notorious projects of the Victorian age. Completed in 1845, the tunnel took six years to build. In that time, 32 workers were killed and 140 were seriously injured. A further 28 people died from cholera due to unsanitary living conditions.

Following the project, a campaign by social reformer Edwin Chadwick highlighted that the overall death rate was worse than for soldiers fighting at the battle of Waterloo. This shocked the public and led to a Government enquiry.

Above: The death rate building the Woodhead Tunnel was worse than for soldiers fighting at the battle of Waterloo.

A change in law followed that made rail companies responsible for the health, welfare and accommodation of navvies. This was one of the earliest examples of how campaigning changed attitudes in the construction.

Over the next 100 years, progress on health and safety was slow and it wasn’t until well into the 20th century that attitudes seriously began to change. Even in the 1960s, safety on construction sites was still not being paid enough attention.

HEALTH AND SAFETY IN THE 1970s

Above: The HSE recorded 166 fatal accidents in 1974 - the year the UK Government passed the Health and Safety at Work Act.

In 1974 the UK Government passed the Health and Safety at Work Act – but the statistics from the time make for sobering reading. The Health and Safety Executive (widely known as the HSE) recorded 166 fatal accidents in the construction sector that year – accounting

for roughly a quarter of all deaths at work.

Throughout the decade, numerous campaigns sought to change hearts and minds, many of them led by the British Safety Council.

HEALTH AND SAFETY IN THE 1980s

In the early 1980s it was still uncommon to wear a hard hat on site and it wasn’t until the end of that decade that the use of hard hats was seriously enforced. In 1981 the HSE started publishing the fatality rates for different employment sectors.

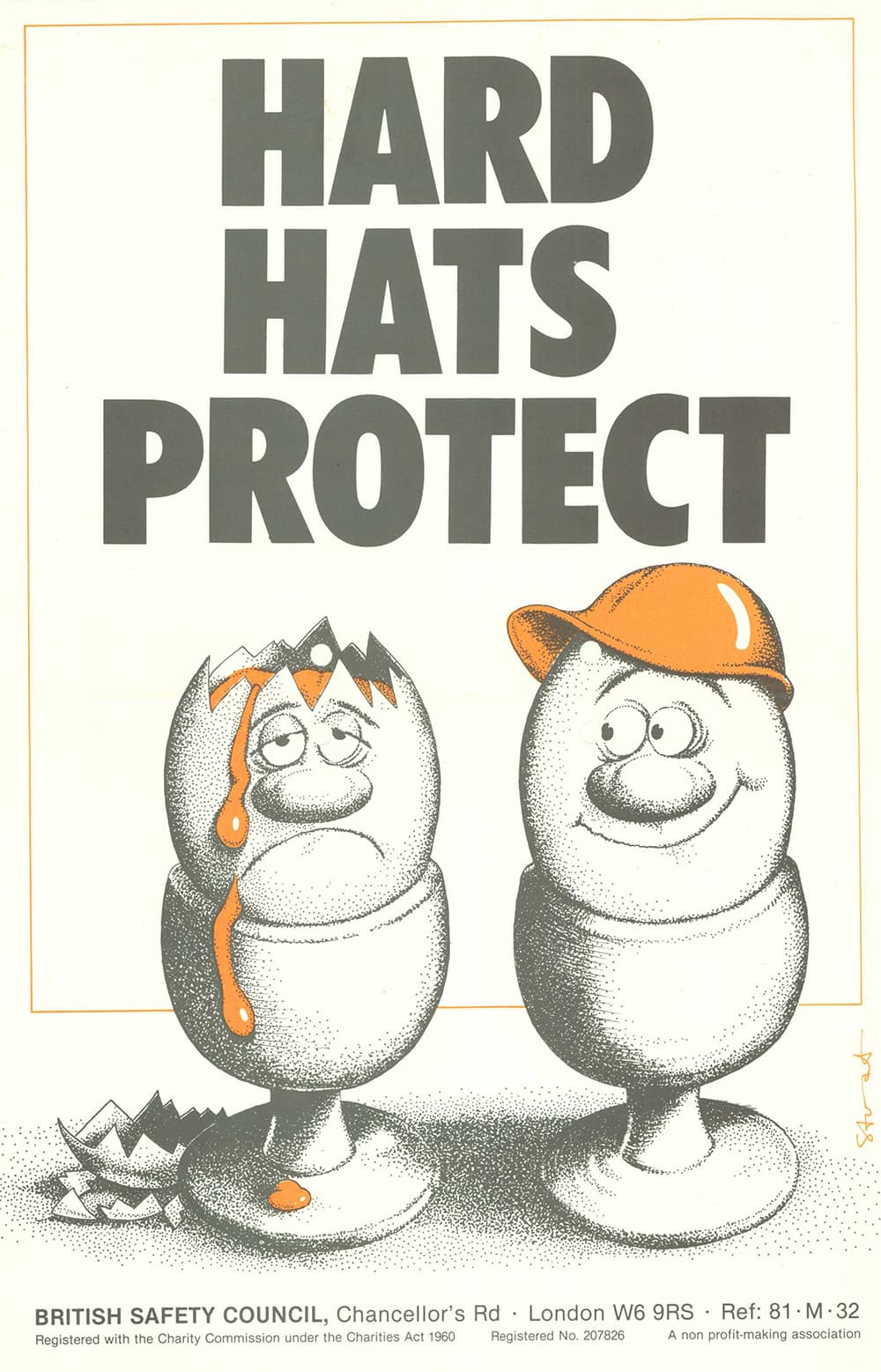

Above: Throughout the 1980s the British Safety Council encouraged the use of hard hats (image courtesy of the British Safety Council).

The rate for construction fatalities was 7.9 per 100,000 workers – nearly four times the rate across the entire British workforce.

Although these figures are discouraging, things were actually improving. There were 116 workers fatalities that year – 50 fewer deaths than when the Health and Safety at Work Act came in, seven years earlier. Also in 1981 the HSE started compiling statistics on major non-fatal accidents.

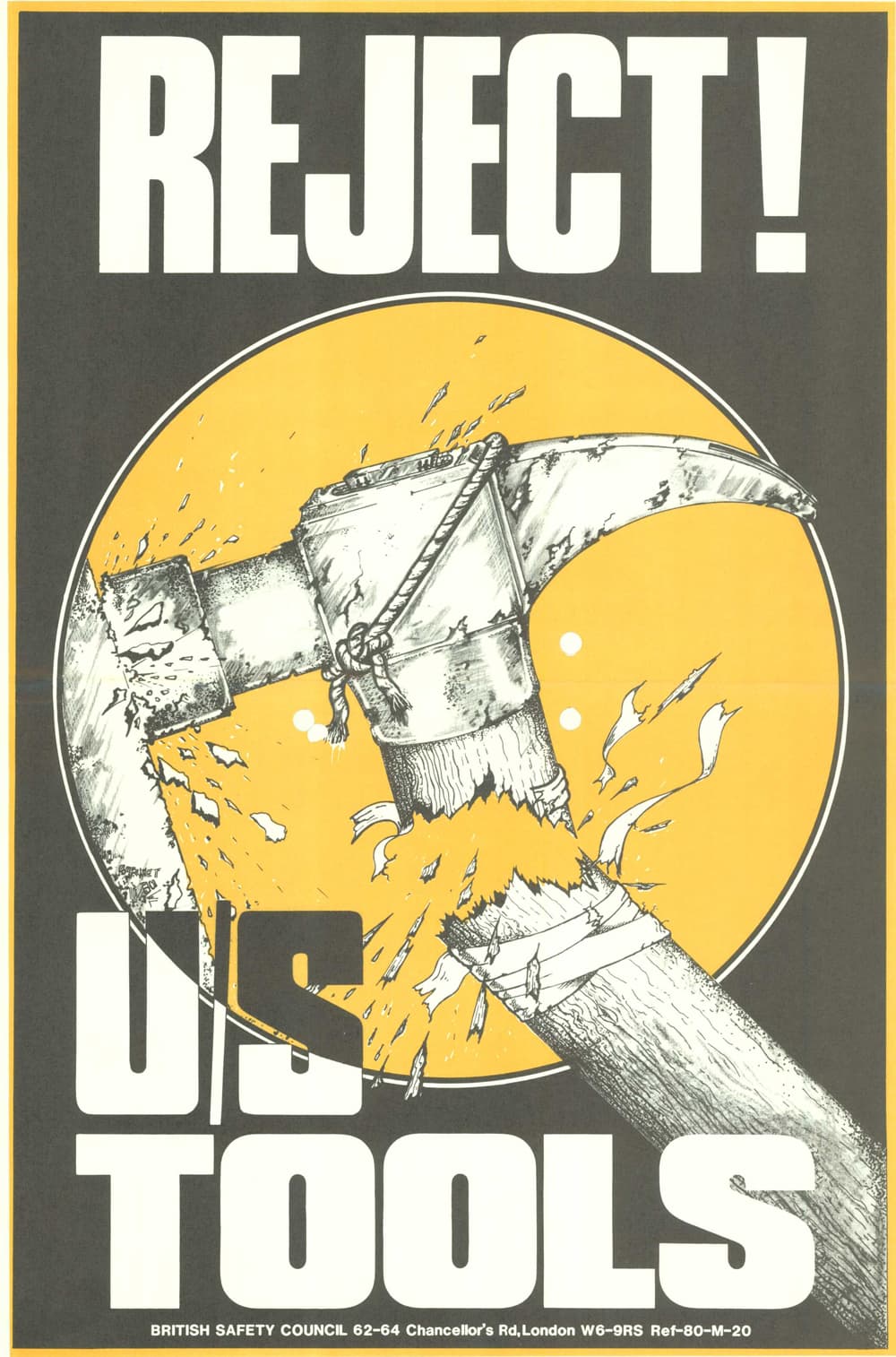

Above: Posters warned workers about the danger of old and unsafe tools (image courtesy of the British Safety Council).

In the construction sector, more than 1,600 injuries were reported – accounting for over a seventh of injuries across all industries. Worried that companies may be cutting back on costs as the UK economy began to slow, the British Safety Council warned workers about the dangers of using old and unsafe tools.

By 1989, the Noise at Work Regulations came into force.

HEALTH AND SAFETY IN THE 1990s

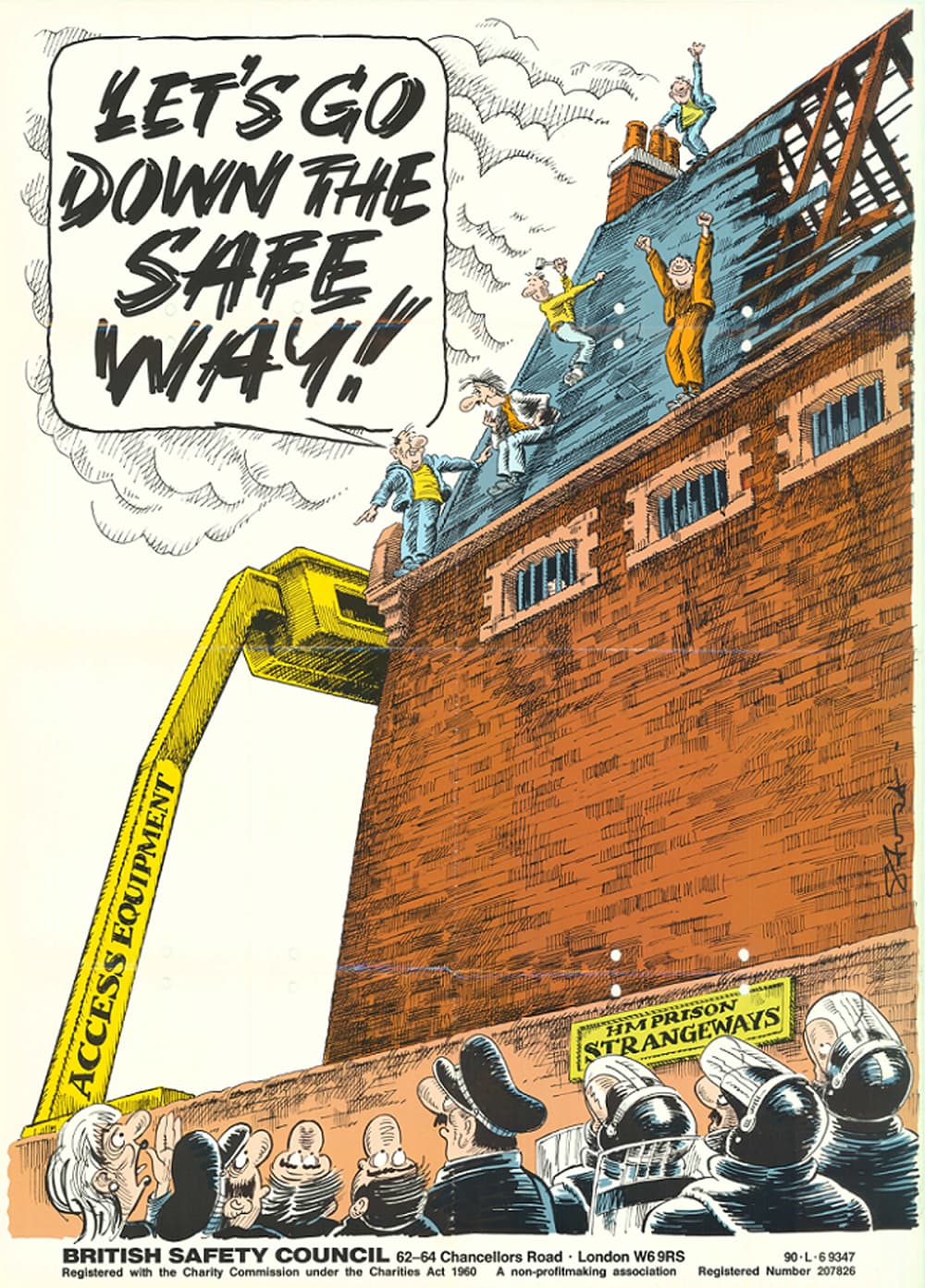

The accident rate continued to fall throughout the 1990s. Safety nets also became more common for people working at height. This coincided with the arrival of new types of plant and equipment, such as high reach excavators and mobile elevated work platforms – known as “MEWPs” or “cherry pickers” – that enabled safer working.

The 1990s also saw a significant push for people to wear the correct Personal Protective Equipment (or PPE), with the Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations coming into force in 1993. But rigorous risk assessments were still an unfamiliar part of the health and safety regime for many on site.

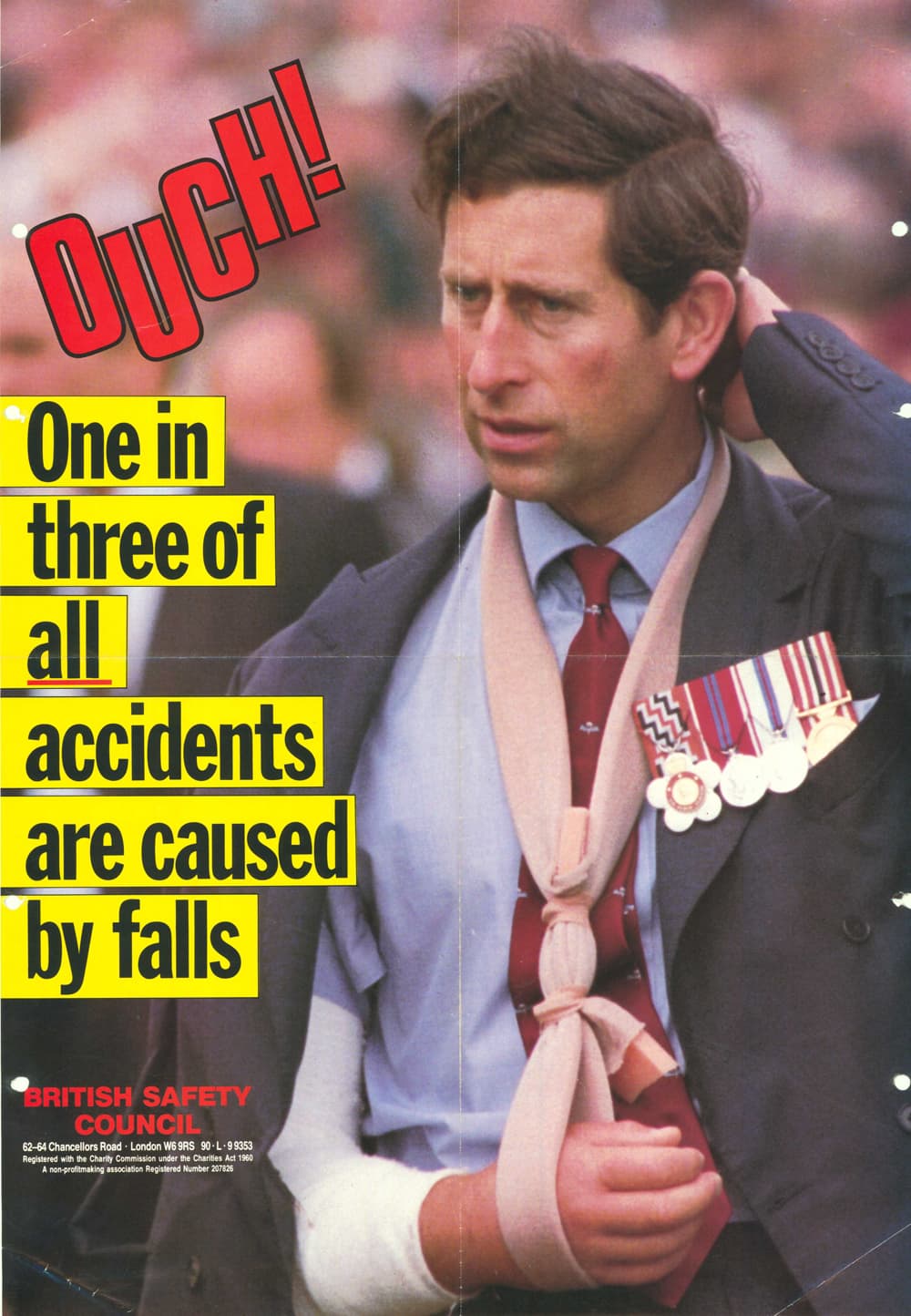

Above: A poster of Prince Charles with his arm in a sling highlighting the dangers of falls – still the biggest causes of accidents and injuries today (image courtesy of the British Safety Council).

In 1994, the Construction Design and Management (or CDM) Regulations were introduced. This forced clients, designers and contractors to coordinate their approach to safety for the first time.

This was also the year that the Channel Tunnel completed; a project that employed over 13,000 people at the height of its construction. A total of 10 workers died building the tunnel – eight of them British. This was obviously a vast improvement on the Victorian tunnellers, but it still left significant room for improvement.

HEALTH AND SAFETY IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Although falls from height remained the industry’s biggest killer, it wasn’t until 2005, that the Work at Height Regulations were introduced. Falls from low height can be just as dangerous as those from a greater height. The Work at Height Regulations led to a marked reduction in the use of ladders on many sites. They were used as a “last resort” as compared to other forms of elevated access.

Above: In 2005 the Work at Height Regulations were introduced (image courtesy of the British Safety Council).

Worker engagement, better training, the involvement of designers and significant emphasis on behavioural change have all helped shift construction towards safer ways of working.

A notable success story is the London Olympic Park, completed in 2012. Around 12,500 workers worked on the Park – clocking up 62 million man hours …with zero fatalities. The accident frequency rate was less than half the construction industry average. It’s an example of what can be done, if we plan, train and remain vigilant.

Above: Around 12,500 workers worked on the Olympic park – clocking up 62 million man hours with zero fatalities (image courtesy of the ODA).

Sadly, this is a rare example. In 2016 – the total number of fatal injuries in construction in the UK was 43 and the fatality rate per 100,000 workers was 1.9.

A lot more work needs to be done to improve occupational health – reducing problems such as dust, and it’s important to remember to wear your PPE, follow the rules, and not get complacent.

Our thanks to the Health and Safety Executive and to the British Safety Council – which is celebrating its 60th Anniversary.

Images courtesy of the British Safety Council, Bechtel, Helen Binet and ODA. We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.

.png?updated=1582727043

)