The World’s Most Remote Buildings

- Youtube Views 7,699,753 VIDEO VIEWS

WHILE the majority of construction activity occurs in and around major urban areas to provide housing, infrastructure and support economic growth, some buildings serve their purpose by deliberately being as far away from the hustle and bustle as possible.

Seldom seen, barely known about and hardly ever visited, we've tracked down the world’s most remote buildings.

BISHOP ROCK LIGHTHOUSE, UNITED KINGDOM

Officially the smallest island in the world with a building on it, Bishop Rock is the westernmost point of the Scilly archipelago and lies 70 kilometres from the closest major town, Penzance, on the United Kingdom (UK) mainland.

Above: The impressive Bishop's Rock Lighthouse (image courtesy of Trinity House).

With the rise of shipping between Britain and North America in the 19th century, numerous vessels were becoming wrecked on the islands on the last leg of their journeys towards Britain, prompting the construction of the lighthouse.

With works commencing in 1847, the original structure was planned to stand 37 metres (120 feet) tall on iron legs, however, the light was never lit on this tower as the building was washed into the sea in 1850 before being commissioned.

Work on the current lighthouse began in 1851. This time, the structure was built from granite, painstakingly shipped out to the remote location.

The challenge of finding suitable terrain on such a small parcel of land meant that the foundation stones had to be laid below the low water line. To achieve this, the project team constructed a cofferdam around the site and pumped the area dry, enabling works to proceed.

Above: Bishop Rock is officially the smallest island in the world with a building on it (image courtesy of David Wilkinson).

First lit in 1858, further strengthening works were carried out in 1881, encasing the original tower in additional granite and raising its height to 49 metres.

With access via boat becoming increasingly difficult, a helipad was installed on the lighthouse roof in 1976. This remained in frequent use until the lighthouse was fully automated in 1992.

TASH RABAT, KYRGYZSTAN

Tash Rabat, in the furthest reaches of Kyrgyzstan’s Naryn Province, served for many centuries as a “caravanserai” or rest stop for traders making their way along the Silk Road between Europe and Asia.

Above: Tash Rabat is located high in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan (image courtesy of Jonathan North Washington).

Believed to have originated as a monastery as far back as the 10th century, the structure offered weary travellers’ safety and shelter as they made their perilous journeys between the two continents.

Featuring 31 rooms and halls with dome-shaped roofs, the entire structure is built from crushed rock and clay sourced from the immediate surroundings.

Above: Tash Rabat is constructed with materials sourced from its immediate surroundings (image courtesy of Michael Turtle).

Though unused today, the site can still be accessed by a lengthy horseback trek. For those wanting to stay the night after such a journey, the site's caretakers offer accommodation in traditional yurts nearby.

SVALBARD GLOBAL SEED VAULT, NORWAY

Nicknamed the "Doomsday Vault” the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on Spitsbergen Island lies 1,300 kilometres from the North Pole and is one of the most remote buildings on Earth for a very important reason.

Above: The "Doomsday Vault" lies within the Arctic Circle (image courtesy of Riccardo Gangale and the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food).

The vault stores the seeds from gene banks around the world, ensuring their survival and protecting global food supplies in the event of large-scale regional or global crisis.

Built by the Norwegian Government in 2008, the location was chosen specifically for its remoteness, lack of tectonic activity and cool climate which helps to maintain the sub-zero temperatures of the vault even in the event of a refrigeration malfunction.

Above: The majority of the building is located within the mountain (image courtesy of Matthias Heyde and the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food).

The facility was constructed by boring into the side of the mountain through 120 metres of sandstone.

The vault’s positioning more than 130 metres above sea level ensures that its contents will remain protected, even in the event of the polar ice caps melting.

With the bulk of the structure located inside the mountain, the only sign of the facility at surface level is its impressive steel and concrete entrance which is topped with an art installation of mirrors, prisms and optic fibres.

HALLEY VI RESEARCH STATION, ANTARCTICA

From the far North to the very far South of our planet, the Halley Antarctic Research station is home to the British Antarctic Survey.

Named “The Sixth” after five previous research facilities succumbed to the elements, the current Halley base is designed to react to the hostile and ever-changing Antarctic environment, greatly increasing its lifespan.

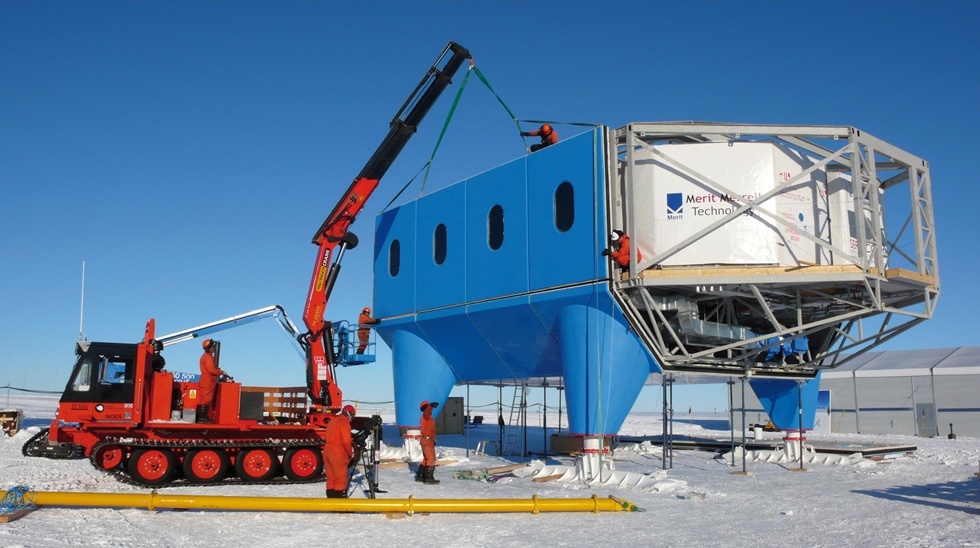

Above: The modular Halley VI Research Station can be moved to endure the ever shifting ice shelf (image courtesy of Anthony Dubber).

The facility consists of several modules laid out in a straight line and orientated perpendicular to the prevailing winds.

This layout causes snow drifts to form on the leeward side, leaving the windward side free from drifts, reducing snow management requirements. It also acts to create a solid ice surface for vehicles to manoeuvre on.

The station’s modules are supported on large steel skis and hydraulic legs that allow them to be raised as snow levels build and moved to alternative locations as necessary.

The base sits on the Brunt Ice Shelf; a 150-metre thick slab of ice that is steadily moving 400 meters closer to the sea each year. Once ice reaches the edge of the shelf, it calves off into the ocean creating icebergs. As Halley base moves closer to the edge of the shelf over time, the modules can be lowered and towed by bulldozers to a new position further inland.

To build this state-of-the-art facility in such an inhospitable and remote location, the modules were prefabricated off-site and test-assembled in South Africa before being shipped to Antarctica.

Above: The station took three summers to assemble after being shipped from South Africa (image courtesy of Andy Cheatle).

Once there, the modules were offloaded and towed to the top of the ice shelf before final assembly could occur.

Construction had to take place in Antarctica’s brief summer periods which last a mere three months – and the scheme took three summers to complete, opening in 2013.

Now operational, the Halley Research Station houses 52 researchers during the summer months whilst 16 remain behind each year to ride out the continent’s extreme winter.

SPHINX OBSERVATORY, SWITZERLAND

From one cold location to another, the Sphinx Observatory in the Swiss Alps is situated 3,571 metres above sea level and is the highest altitude construction project undertaken in Europe to date.

While the observatory is indeed remote, its construction was made possible by the near 20-year mission to conquer the Alps by rail and the opening of Europe's highest railway station nearby in 1912.

Above: The Sphinx Observatory is the highest building in Europe.

This feat made the construction of the observatory possible, with materials and workers able to be transported to within 100 metres of the site.

Since opening in 1937, the observatory has undergone numerous upgrades as technology has progressed and is still a major research centre for astronomy, glaciology and meteorology.

The observatory offers tourists an opportunity to take in the view from “The Top of Europe” and can be accessed from an elevator shaft bored through the mountain that links with the Jungfraujoch rail station.

ESO HOTEL, CHILE

In the depths of Chile’s Atacama Desert sits the breath-taking Eso Hotel.

Featuring prominently in the 2008 James Bond film Quantum of Solace, the hotel is not open for public use and in fact, serves as accommodation for researchers working at the European Southern Observatory.

Above: The ESO Hotel blends into the desert to minimise the visual impact on its surrounds.

Built to minimise its impact on the surrounding desert, the hotel lies within a natural depression in the landscape with only its central garden dome visible on the horizon.

Built primarily with concrete – as brick and steel were deemed economically impractical and did not fit with the desert context – the hotel offers 108 rooms, 18 offices, a sauna, gardens, swimming pools and a library, the hotel has been nicknamed the “Oasis for Astronomers”.

Sitting at an altitude of 2,400 metres, and with less than 1 cm of rainfall each year, tankers brought water to the site to mix the concrete during construction. To this day, the complex still relies on regular water deliveries to remain functional.

Above: The materials used in the hotel help to insulate its interior from the extremes of the desert (image courtesy of I. Werz-Rein).

Dyed red to blend with its surroundings, the hotel’s concrete façade also provides significant thermal mass, helping to regulate its internal climate throughout the extremes of the desert day.

Images courtesy of National Maritime Museum (UK), Trinity House, David Wilkinson, Scilly Today, Jonathan North Washington, Martin Jung, Michael Turtle, Crop Trust, Heiko Junge, Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Riccardo Gangale, Matthias Heyde, Anthony Dubber, James Morris, Hugh Broughton Architects, British Antarctic Survey, Dave Southwood, Andy Cheatle, Thomas Schmiedbauer, IUB Engineering AG, ESO, José Francisco Salgado, Roland Halbe, G. Hudepohl and I. Werz-Rein.

We welcome you sharing our content to inspire others, but please be nice and play by our rules.